Landscapes

1.07 Landscapes8

Tectonic events, geological composition, water, erosion, deposition, climate, soil and vegetation all determine the visible features of an area of land, the landscape. These features and characteristics influence the animals that occur there and how people there make a living.

Twenty-three iconic landscapes of Namibia are defined in this map, and described in the pages that follow. Almost all of these landscapes could be subdivided into smaller elements. A good example is the Namib Sand Sea, which could be divided into a number of dune fields, each characterised by the different types of dunes which have been formed by the local impacts of wind speed and direction, the supply of sand and surrounding topography and vegetation.

1. Central-Western Plain

Photo: J Mendelsohn

This broad landscape stretches east from the Coastal Plain (right) across much of central Namibia. Elevations in this landscape rise gradually from about 500 metres above sea level in the west to approximately 1,000 metres in the east. The plain is punctuated by many inselbergs, most of which are small granite hills, but it also encompasses the large granitic Erongo and Paresis mountains and the Brandberg and Spitzkoppe. Rock formations surrounding the inselbergs are mainly metamorphosed products of ocean sediments that were forced up during the formation of Gondwana.

The Escarpment (below right) extended across this area before it was eroded and smoothed away by rivers into these plains. Such erosive forces are hard to imagine in today's arid climate, but we are reminded of their power when the sizeable Khan, Omaruru, Swakop and Ugab rivers, which drain the landscape, occasionally flow.

East of the Erongo Mountains most of this landscape area is divided into large farms used for livestock, wildlife and tourism. Rainfall decreases towards the west and only the hardiest of plants, wildlife and domestic stock live in the plain's most arid reaches.

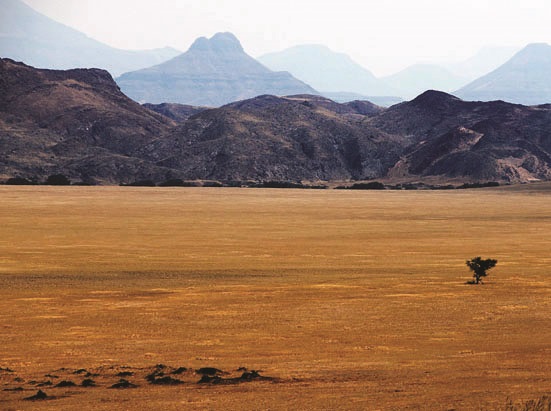

2. Coastal Plain

Photo: A Jarvis

The Coastal Plain developed after Gondwana split up about 132 million years ago and the uplift of the marginal escarpment of southern Africa, possibly sometime in the Late Cretaceous (around 70–65 million years ago). The broad Coastal Plain forms an apron along the entire length of Namibia's coast except where it is covered by dunes of the Namib Sand Sea. Away from those dune fields, the surface is underlain largely by gravel and thin layers of sand, granite outcrops and dolerite dykes and sills. These and other rocks have been planed off to form an even surface, possibly by the Atlantic when sea levels were much higher than they are at present.

This is the most arid area of Namibia. Rain seldom falls and the only regular precipitation comes in small quantities of fog. As a result, vegetation is extremely sparse, being limited to scattered tufts of grasses, and shrubs with special adaptations to conserve, collect and/or absorb moisture. Almost everyone on the Coastal Plain is urban, living in one of the four towns of Lüderitz, Walvis Bay, Swakopmund and Henties Bay. Most of the Coastal Plain is conserved in contiguous parks stretching between the Kunene and Orange rivers.

3. Cuvelai

Photo: H Denker

This unusual drainage system is characterised by a dense network of shallow channels known locally as iishana (oshana, singular). The landscape is extremely flat, leading the iishana to split and rejoin repeatedly. During the rainy season, flows of water from higher, wetter areas of the northern Cuvelai in Angola may be supplemented by local heavy rainfalls. About 100 iishana flow into Namibia spread across an area 170 kilometres wide, which gradually converge on the Omadhiya lakes. About a quarter of Namibia's population lives in the Cuvelai in homes and smallholdings spread across the landscape. Significant numbers of people now live in several rapidly growing towns in the Cuvelai.

Large numbers of fish are harvested when the iishana flow and the Omadhiya lakes fill. Crops are grown for domestic consumption on relatively fertile soils around households, while livestock graze the commons in the iishana and outside the smallholdings. Fresh groundwater is available in hand-dug wells.

4. Escarpment

Photo: A Martin

The Escarpment clearly and abruptly separates the Coastal Plain (above) from higher ground to the east. It is best developed in central and southern Namibia where it reaches its maximum elevation of 2,350 metres above sea level at the flat-topped Gamsberg, seen here. In northwestern Namibia, the Escarpment is not as well defined and is spread across a broader zone. Between Usakos and Khorixas erosion has largely removed the highlands and Escarpment, forming a much gentler slope inland. It is not clear if the Escarpment's formation was a consequence of the break-up of Gondwana, or if it was formed earlier by some other process. Namibia's Escarpment is part of the Great Escarpment that runs more or less continuously around the margins of southern Africa from the Congo River to the Zambezi.

The two permanent rivers on the northern and southern boundaries of Namibia, the Kunene and Orange, cut through the Escarpment, as do the ephemeral Kuiseb, Swakop, Huab, Hoanib and Hoarusib rivers. Environmental conditions change rapidly between the relatively wetter and more vegetated top of the Escarpment and the arid and sparse plant cover lower down.

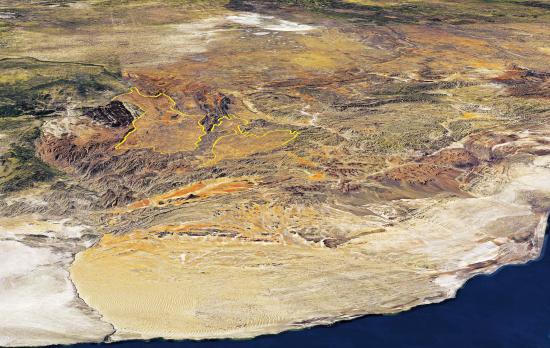

5. Etanga–Epembe Plains

Photo: Google Earth and Bing images via Terraincognita, draped over Shuttle Radar Topography Mission data

Viewed from high above the Kunene River Mouth, this area consists of two broad, relatively flat plains surrounded and separated by the rugged Kaokoveld Hills. As shown in this satellite image, the northern area slopes down towards the Kunene River. Ephemeral streams in the southern area flow southwards into the Hoarusib River. The geology underlying these plains is like that of the surrounding hills. At elevations of over 1,100 metres above sea level, these plains are high above the lowlying Coastal Plain to the west and are thought to have possibly formed as a result of glaciation.

Rural livelihoods and economic circumstances here are very similar to those in the Kaokoveld Hills, with Etanga, Epembe and Okanguati being the only significant centres. Soils are shallow and vegetation is sparse in this arid environment. Fresh water is obtained from hand-dug wells in dry river courses, and from springs and boreholes.

6. Etendeka Tablelands

Photo: S Kellerman

These distinctive flat-topped mountains of northwestern Namibia are underlain by horizontal layers of solidified lava that erupted some 132 million years ago when South America and Africa started to break apart. The tablelands are consequently made up of successive flows of basalt and volcanic rocks derived from explosive activity. The spectacular Grootberg and the surrounding flat-topped hills are good examples of this landform. The name 'Etendeka' is derived from the Otjiherero term for layered or stacked.

The Etendeka Tablelands is an arid landscape where rainfall is low and unpredictable and evaporation rates are high. Plant and animal life is thus sparse and limited to hardy types. A number of springs bring subterranean water to the surface in this area, which supports localised areas of greenery. The few people who live here make a living largely from remittances, grants, livestock and incomes derived through conservancies and tourism.

7. Etosha Saltpans

Photo: P Lambrecht

Etosha Pan and the smaller pans around it lie in a very shallow basin. The pans are normally dry, but can fill from local downpours. The main pan sometimes receives water from the Cuvelai when there is sufficient water in its channels to collect in the Omadhiya lakes and flow down the Ekuma River into Etosha Pan. Etosha Pan covers an area of 4,800 square kilometres today. However, up until about 4 million years ago the Kunene River used to flow into the Cuvelai drainage system, inundating a much larger area than today. At that time, Etosha was a giant lake that extended into southern Angola.

Salts in the pans and the surrounding soils have accumulated from dissolved minerals washed into the area by the Kunene and other rivers over the many eons. With nowhere farther to flow, the floodwaters evaporate leaving behind fine sediments and minerals.

When Etosha floods, flamingos often arrive in great numbers to breed and feast on the abundance of tiny organisms – algae, cyanobacteria, diatoms, flies, shrimps and other invertebrates – that hatch from spores and eggs hidden in the salty clays.

8. Gamchab Basin

Photo: P Cunningham

This landscape in southeastern Namibia is named after the Gamchab River, the largest of many small ephemeral rivers and streams that drain the basin. Rainfall is low, falling erratically in either summer or winter. Temperatures and evaporation rates are often very high, all of which makes this a harsh environment. The plant cover consists mainly of low shrubs and sparse grasses. Game and small-stock farming are the main economic activities in this remote corner of Namibia.

The Gamchab Basin is dominated by large, open valleys of gently south-sloping ground underlain with rocks of the Namaqua Metamorphic Complex and sediments and dolerites of the Karoo geological era. Much of the rock has been eroded down to a flat surface, most likely by glaciers during the Karoo era. This flat plain is crossed with ephemeral streams that drain into the Orange River along its southern boundary, where it drops into the rugged landscape of the Orange River Valley.

9. Inselberg Intrusions

Photo: J Mendelsohn

Most inselbergs (literally 'island mountains') are too small to map but are still prominent features of the landscape. Generally rounded in form, inselbergs are normally mounds of granites or gneisses that are the remainders of intrusions of magma that cooled over many years. Interlocking crystals make granite largely impermeable and thus resistant to erosion, preserving the forms of these intrusions as prominent rock masses as the softer rocks surrounding them are removed by weathering and erosion. Inselbergs are characteristic of arid and semi-arid terrains. Namibia's most prominent inselbergs are Brandberg, Erongo Mountains, Paresis Mountain (seen above) and Spitzkoppe. The surfaces of those in the far west are dominated by bare rock, with soil and plants being restricted to valleys and crevices. Much more soil and vegetation cover the inselbergs in the east where they receive more rain than their western counterparts. Many of the plants and animals that occur in these isolated highlands are restricted to them and found nowhere else

Strictly, some isolated mountains such as Waterberg and Mount Etjo are not inselbergs because they were not formed from intrusions of igneous rock.

10. Kalahari Sandveld

Photo: H Baumeler

This extensive flat area extending over most of northern and eastern Namibia is covered by largely unconsolidated sands of the Kalahari Basin. The sands have been moulded into dunes in many areas where they form long lines across the landscape. Dunes in the more arid areas are sparsely vegetated and more active, their shapes and sizes being moulded slowly by wind. Dunes in higher-rainfall areas of the north and northeast that were once arid are now covered in trees and shrubs.

Watercourses that originate within the Kalahari Sandveld are normally dry because rain rapidly infiltrates the sands, and the many small pans scattered across the landscape only collect and hold water for short periods following thunderstorm deluges. In the northeast, the Okavango, Zambezi and Kwando rivers carry water from high-rainfall areas in Angola across the Kalahari Sandveld.

Apart from holding little moisture, the sandy soils hold few nutrients. Only the soils along ancient watercourses and interdune valleys are somewhat fertile and are used to grow crops. Elsewhere, livestock and wildlife graze and browse the vegetation, although wildlife is mainly restricted to areas managed for conservation. The Kalahari Sandveld is sparsely populated by people. Modest yields of groundwater are widely available from porous aquifers.

11. Kamanjab Plain

Photo: Google Earth and Bing images via Terraincognita, draped over Shuttle Radar Topography Mission data

The Kamanjab Plain is underlain by some of the oldest granitic and gneissic rocks in Namibia. It is relatively flat with scattered low, rolling hills of piled boulders formed through weathering of great blocks of granitic-gneiss rocks. The plain lies more than 1,000 metres above sea level, but is deeply incised in the west by the Huab and Ombonde rivers as they cut their ways towards the coast.

Livestock and game farming, trophy hunting and tourism are the major economic activities across this landscape where the vegetation is dominated by mopane and acacia woodland. Total rainfall seldom exceeds 300 millimetres per year and is often extremely variable. Hilly ground is rocky, while Calcisol soils cover the extensive plain. Evaporation concentrates calcium carbonate in these soils into blocks of white calcrete which dot the surface.

12. Kaokoveld Hills

Photo: P Lambrecht

This must be the most remote, rugged and mountainous landscape in Namibia. Elevations range between 1,000 and 1,900 metres above sea level. Few people live here and there are only a few tiny towns on its outskirts, such as Orupembe and Sesfontein. Livelihoods are based largely on small stock and cattle, which are often moved to areas where forage is available around northwestern Namibia and southwestern Angola. Almost all income in this arid environment is from occasional sales of livestock and from remittances, social grants and tourism revenue.

The landscape is underlain by some of the oldest rocks in Namibia, most being metamorphic and folded between 2,600 and 1,800 million years ago. That this is an ancient landscape is suggested by the presence of glacial valleys that cut through older topography more than 300 million years ago. The best example is the Kunene Valley which cuts through 1,500 metres of older topography in places.

13. Karas Mountains

Photo: Google Earth and Bing images via Terraincognita, draped over Shuttle Radar Topography Mission data

Rising from the southern plains of the Nama Karoo and Kalahari Sandveld are the Karas Mountains, two prominent landmarks which comprise uplifted blocks of metamorphic basement rocks that are about 1,200 million years old. These ancient rocks are overlain by a relatively thin veneer of sedimentary sandstones, limestones and shales. More recent erosion has dissected the blocks of basement rocks so much in some areas that it is difficult to imagine that the mountains originally had flat tops.

Most rain here falls in the late summer with annual averages between 150 and 200 millimetres, but it varies greatly from season to season. Because moist air is forced up over the mountains, they often receive slightly more rain than surrounding lower areas. Soil and vegetation are limited to valleys and clefts among the expanses of bare rock. Sheep and goat farming is the main economic activity in this area. Farms are large, and few people live in this rugged, harsh but impressive landscape.

This satellite image views the landscape from southeast to northwest. The image has been draped over elevation data to illustrate the area's topography.

14. Karstveld

Photo: J Mendelsohn

The Karstveld is underlain exclusively by rocks formed from sediments deposited 750–600 million years ago in a shallow sea covered by mats of microbial organisms. These rocks are quite soluble in rainwater and thus slowly dissolve over time, leaving cavities that may develop into extensive aquifers, cave systems and underground lakes. Lake Guinas and Lake Otjikoto were such underground lakes before the ground above them eroded so thin that it collapsed. There is little surface runoff from rain in this area because most of it rapidly drains into the ground and underground cavities. Water that evaporates from the soil leaves behind dissolved calcium carbonate which aggregates into distinctive calcrete rocks that are abundant around the Karstveld, and in the adjacent Etosha National Park.

Some caves are important archaeological sites, with an early prehuman primate, named Otavipithecus, being found near Berg Aukas. Many endemic species of insects and some fish species are also known from the Karstveld where they have evolved in isolated caves and lakes. Much of the landscape is used for livestock farming. Valleys in the higher-rainfall Otavi–Grootfontein–Tsumeb area, known as Namibia's 'Maize Triangle', have relatively fertile soils that support the large-scale production of maize, cotton and sunflower, and the irrigated horticulture of high-value fruit and vegetables.

15. Khomas Hochland

Photo: D Ruppel

These highlands were originally formed when the Kalahari and Congo cratons collided to form the continent of Gondwana about 550 million years ago. The rocks that dominate this landscape are mica-rich schists formed from sand and mud deposited on the ocean floor that had separated the two cratons. As they collided, the marine sediments were heated, squeezed and folded into mountains much like the Alps of Europe or the Andes of South America.

More recently, rift valleys formed in these highlands, such as the one stretching between Okahandja and Windhoek. Along the edges of the rifts are faults in which water collects and feeds into aquifers, forming the major groundwater sources that enabled Windhoek to establish long ago. Windhoek with its large population and various economic activities is at the heart of these highlands. Much of the Khomas Hochland has been eroded into rolling hills. These hills are the sources of the westward-flowing Kuiseb and Swakop rivers that flow to the Atlantic, and the southeastward-flowing Black and White Nossob rivers that drain into the Kalahari Sandveld. The hills are largely covered in grasses and a sparse cover of shrubs and small trees. The tallest trees grow along drainage lines where their roots enjoy better access to groundwater. Livestock and game farming and tourism are the main economic activities outside Windhoek's city limits.

16. Nama Karoo Basin

Photo: J Mendelsohn

This extensive, flat landscape that dominates much of southern Namibia is underlain by horizontal layers of sediments. One of the few breaks in the landscape is the well-known Brukkaros Mountain (also known as 'Geitsi Gubib'), an extrusion of igneous rock that rises some 650 metres above the surrounding plain. Sills of dolerite (dark volcanic rock) pushed through the sediments, especially around Keetmanshoop, and with weathering have given rise to the Giants' Playground setting. The iconic quiver tree or kokerboom (Aloe dichotoma) thrives on the rich soil produced from the dolerites. To the east, the Nama Karoo Basin extends under the Weissrand Plateau and Kalahari Sandveld landscapes, while the Escarpment to the west separates the Nama Karoo from the Coastal Plain.

The ephemeral Fish, Konkiep and Löwen rivers flow southwards across this landscape towards the Orange River. Vegetation is sparse as a result of the arid climate. Extensive farming with small stock is the predominant, widespread rural economic activity. Significant irrigation schemes are associated with the Hardap and Naute dams and a third is planned for development at Neckartal Dam. Economic activities concentrated in towns, especially the larger regional centres of Mariental and Keetmanshoop, are mostly related to agriculture.

17. Namib Dune Fields

Photo: P van Schalkwyk

The Namib dune fields are probably Namibia's most iconic landscape, attracting tourists from all over the world to its central Namib Sand Sea and Sossusvlei. Recognised for its uniqueness, the Namib Sand Sea is one of Namibia's two World Heritage sites (the other being Twyfelfontein in northwestern Namibia); it is the largest stretch of Namib dunes and lies between Lüderitz and Walvis Bay, stretching some 400 kilometres from north to south and up to 150 kilometres inland from the coast.

All of the Namib sands were transported by the Orange River from the interior of southern Africa to the Atlantic Ocean. From there, ocean currents moved the sand onshore and it was blown inland by strong southwesterly winds. The encroaching march of the dunes northwards from the main body of the Namib Sand Sea is halted by the Kuiseb River, which flows just often enough to wash the encroaching sand away. Further north, two smaller dune fields are likewise halted by the Hoarusib and Kunene rivers, respectively.

It is hard for plants to root and grow in the shifting sands. The extreme aridity adds another constraint, which also limits animal life. Most organisms that live here have special adaptations to this challenging environment, and occur nowhere else in the world.

18. Naukluft Mountains

Photo: JB Dodane

Perched on the edge of the Escarpment, this massif of rock was shifted by tectonic forces from its original position, southwestwards, during the formation of the supercontinent Gondwana; it moved at least 80 kilometres. The Naukluft Mountains rise steeply along their western margin, reaching 500 metres above the Coastal Plain. The tops of the Naukluft Mountains are surprisingly flat in places, and some evidence suggests they were eroded down by glaciers some 300 million years ago. The deep Büllsport Valley – that separates the two halves of the Naukluft Mountains, and along which the Tsondab River now flows to Tsondabvlei – may have been carved by a glacier.

Both the Tsondab River and the Tsauchab River (which flows to Sossusvlei) have some tributaries that originate in the Naukluft Mountains. Most of the Naukluft falls within the Namib-Naukluft National Park and supports a diverse fauna and flora adapted to this rugged arid landscape.

19. Northeastern Wetlands

Photo: Gondwana Collection

Low-lying areas alongside the Okavango, Kwando, Zambezi and Chobe rivers become flooded wetlands from time to time. Those of the Kwando can flood at any time, while other floodplains are normally inundated in late summer. The floodplains comprise channels and oxbow lakes flanked by grasslands. Geological faults constrain the extent of the floodplains in the south. Water from the Okavango Delta can augment the wetlands via the Selinda Spillway, which flows into the Kwando River and Linyanti Swamps. Lake Liambezi is often dry but becomes one of the most productive wetlands in Namibia when it fills with water from the Zambezi via the Bukalo Channel or Chobe River. The Okavango River forms Namibia's border with Angola for some 450 kilometres, between Katwitwi and Andara, before crossing the Caprivi Strip to enter Botswana at Mohembo.

Woodlands grow on the highest elevations of this landscape, beyond the reach of floodwaters, while grasslands and then reedbeds grow in successively lower, more frequently inundated habitats. The wetlands support a wealth of plants and wildlife, and are central to KAZA, the Kavango–Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area.

20. Ocean Islands

Photo: S Rankl

Fourteen small islands and numerous rocks lie just off the coast of southern Namibia. The largest of these is Possession Island in Elizabeth Bay, south of Lüderitz. Others are Albatross, Halifax, Hollam's Bird, Ichaboe, Long North, Long South, Mercury, Penguin, Pomona, Plumpudding, Little Roastbeef, Seal and Sinclair islands. In the 1840s the islands became the centre of an international dispute between Britain and Germany, both claiming the rights to the islands' plentiful and valuable guano deposits. Up to 10 metres of guano was stripped off certain of the islands between the mid-1840s and mid-1890s9. The islands remained under South African control up until 1994, when they were returned to Namibia. The islands are now protected as major breeding colonies for seabirds and seals within the Namibian Islands' Marine Protected Area. The majority of the global population of breeding African penguins, Cape gannets, bank cormorants, crowned cormorants, Cape cormorants, African black oystercatchers and Hartlaub's gulls breed on these islands.

Most of the islands are low-lying ancient metamorphic rock swept over by erosive waves and winds. Very little vegetation manages to grow in this tough, weather-beaten environment.

21. Orange River Valley

Photo: P Cunningham

The Orange River has cut deeply into much of its course between Namibia's eastern border with South Africa and the river's mouth near Oranjemund. The incision of the river has been caused by a change in its base level, either through a drop in sea level or the uplift of the subcontinent. The base level determines the rate of river flow and erosion: the greater the difference in altitude between upstream and downstream, the greater the gravitational pull on river water, speed and erosional energy.

Namibia owes much to the Orange River. It has transported diamonds to the coast from the interior of southern Africa; and it has provided plentiful water that supports irrigation schemes along its banks, which produce high-value table grapes and other export-quality products. The topography of the valley is extremely rugged, almost inaccessible in places. Summer heat is often extreme, rain is rare, evaporation is substantial and soil and plant cover are sparse away from the river's floodplains and banks. This environment is harsh!

22. Rehoboth Highlands

Photo: Google Earth and Bing images via Terraincognita, draped over Shuttle Radar Topography Mission data

This highland plateau ranges between 1,400 and 1,700 metres above sea level. Elevations are highest in the north and west giving rise to small rivers that drain in a southeasterly direction. The source of the Fish River is in the Rehoboth Highlands. Ancient basement granites and complexes of metamorphic rocks (created under intense pressure and heat) underlie much of the plateau. Many igneous inselbergs and small volcanoes dot the landscape. The volcanoes erupted about 52 million years ago and their viscous lava flows solidified on the surface of the plateau, which therefore must have formed before the volcanoes erupted.

Sheep, goats, cattle and wildlife are farmed here, while additional rural income is derived from tourism. Vegetation is dominated by acacia trees and shrubs, and grasslands, much of which grow on shallow Calcisol and Cambisol soils. Annual rainfall averages between 200 and 300 millimetres. The main urban centre in the landscape is Rehoboth. This image provides a view of the landscape (outlined in blue) from east to west.

23. Weissrand Plateau

Photo: H Baumeler

The western edge of the Weissrand Plateau is a long, low but prominent cliff that runs for about 300 kilometres east of the road between Mariental and Keetmanshoop. East of the cliff, the plateau is underlain by Karoo-age rocks covered by a thin calcrete limestone layer before it disappears under dunes of Kalahari sand. The entire plateau is pockmarked with dolines, small circular depressions or sinkholes dissolved out of the calcrete with short drainage lines leading into them; they are a prominent feature of the landscape. Small remnant portions of this landscape are found east of Maltahöhe against the Escarpment that divides the Namib Desert and Coastal Plain from the rest of Namibia.

Farmers in this area make an income from sheep, cattle, goats and wildlife; the latter through game meat, game sales, trophy hunting and non-consumptive tourism. Farms in the area are large because of their low carrying capacity, many comprising more than 10,000 hectares. Grasses and small shrubs dominate the vegetation, while larger shrubs and small trees grow around the dolines where they have greater access to water.

Submerged offshore Namibia

Photo: Google Earth and Bing images via Terraincognita, draped over Shuttle Radar Topography Mission data

Although hidden, the Namibian continental margin has many notable features, including some of the world's largest slumps, which are created when giant masses of sediment and rock slide down the slope of the continental shelf into the ocean depths. The northernmost part of the continental shelf is relatively narrow, being less than 50 kilometres wide. Immediately south of this zone is the Walvis Ridge, a submerged mountain chain that rises more than 3,000 metres from the seabed and extends for over 2,500 kilometres in a northeast–southwest direction. Isolated flat-topped volcanic seamounts (known as guyots) also occur. One, the Tripp Seamount located near Namibia's border with South Africa, rises from depths greater than 800 metres to within less than 100 metres of the surface.

The marine environment is driven by two powerhouses: the Benguela Current and strong, southerly winds. Together they bring nutrient-rich water from the depths of the sea up to the sunlit surface. Here, these waters nourish and sustain tiny plants and animals, which in turn feed bigger marine organisms, fish, birds and mammals, including humans across the world that consume marine foods from this biologically rich ocean environment.