Natural capital and services

Natural capital is broadly defined as Earth's stock of natural resources – its minerals, soils, air, water and all living organisms. Through a relatively new discipline known as 'natural capital accounting' it is now possible to take stock of these assets in physical and monetary terms, which in turn can be used to inform policy and guide development for long-term sustainability. This method of accounting involves mapping the extent and condition of natural capital and the services provided.

The value of a service is often generated by a combination of natural and human capital. For example, a natural resource gains in use and value when a road is built that improves access to the resource. The capacity of the environment to supply services varies with topography, climate, ecosystem type and condition, while human demands for those services vary with population density, income and location, for example.

The values of five services are described here: carbon storage, fuel wood provision, game production, livestock production, and nature-based tourism. The maps show the benefits that are jointly derived from nature and human inputs, expressed in terms of gross output (revenues) or value added.

Photo: J Mendelsohn

Photo: A Jarvis

Photo: T Robertson

The environment provides three types of services. First, provisioning services offer natural biomass, such as fish or fuel wood, and fresh water. Second, regulating services improve the quality of various ecological assets; for example, vegetation cover prevents soil erosion and regulates runoff, thereby partially controlling the volume and quality of water resources. Third, cultural services, such as beauty, rarity and diversity, are intangible assets that affect how we value the natural environment; these services include the use and value of the natural environment for recreational and educational purposes, and for the enjoyment of future generations.

10.14 Estimated value of carbon storage, 201817

Plants take up (or sequester) carbon from the atmosphere as they grow, which accumulates in plant biomass above and below the ground, and in the surrounding soils. When natural vegetation (or soil) is degraded or cleared, much of this carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere. The amount of carbon released is even greater if the vegetation is burnt as charcoal or by bushfires. These carbon emissions contribute to global climate change, which is expected to lead to a variety of detrimental environmental changes. Based on data derived from satellites, it is estimated that approximately 1.4 billion tonnes of carbon are stored within Namibia's vegetation and soils. Hypothetically, the total costs of damage avoided by maintaining standing vegetation and healthy soils globally are over 1,774 billion Namibian dollars per year, while the avoided costs of damage to Namibia are also substantial at just over 1 billion Namibian dollars per year.

10.15 Estimated value of fuel wood used in Namibia, 201818

Namibia has an estimated 300 million cubic metres of standing stocks of fuel wood available for use, with a sustainable yield of about 9 million cubic metres per year. Total national demand for firewood was estimated to be 1.05 million cubic metres per year in 2018, generating a net income of some 1.07 billion Namibian dollars per year. While this is broadly sustainable, there are areas of the country where fuel wood collection has negative impacts on the condition of ecosystems. The distribution of fuel wood, and therefore its value, through Namibia is irregular. The northern areas of the country are highly valuable in terms of the provision of fuel wood. Further south and west, however, woody biomass is limited, yet still provides value to a relatively low-density population.

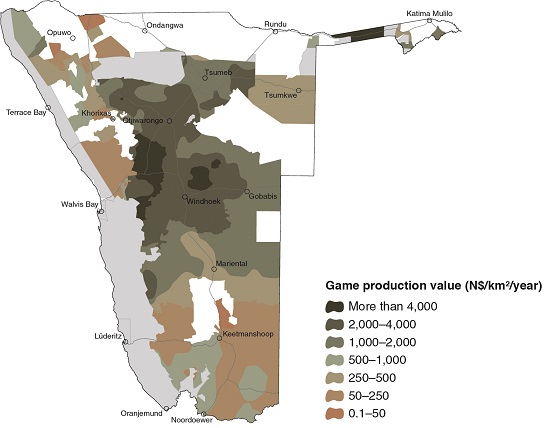

10.16 Estimated value of game production, 201919

Wildlife in Namibia is used for trophy hunting, live sales and meat produce. As yet, there are no comprehensive data on lands set aside for wildlife, and there are no nationally collated statistics on managed game numbers or offtake. In 2016, a total of 3,765 individual clients were reported to have hunted game trophies in Namibia on at least 625 registered game farms and in 38 communal conservancies, generating approximately 360 million Namibian dollars in expenditure (at 2019 prices). Over 90 per cent of trophy hunting fees were generated on freehold lands, 7.5 per cent on communal conservancies, and the remainder on state concessions. Based on existing literature on game densities, prices and sustainable offtake rates, existing game stocks are estimated to have the potential to generate an additional 543 million Namibian dollars per year in terms of meat production.

Photo: J Mendelsohn

While farming is limited by Namibia’s arid climate, depauperate soils and a scarcity of perennial water, large tracts of Namibia are well endowed with suitable habitat for wildlife. Coupled with growing international demands for wildlife hunting and meat, this endowment has led to the development of a substantial wildlife economy on freehold and communal lands. A significant part involves the consumptive use of game for the sale of meat, for hunting for trophies and meat, and the raising of game for live sales. Many farmers have switched entirely to wildlife-based activities while others have added wildlife production to their livestock operations. Of the latter, some have adopted a truly mixed system of livestock and wildlife, in which wildlife roam freely; others have adopted a 'dual' farming system with areas for livestock separated from areas for wildlife. On freehold land, this type of mixed farming takes place on about 256,000 square kilometres (72 per cent), followed by livestock farming (19 per cent) and land used exclusively for wildlife (9 per cent).

10.17 Estimated value of domestic livestock production, 201920

Grazing and browse provided by natural vegetation enabled Namibia to produce livestock worth some 4.35 billion Namibian dollars in 2019. Values vary across the country depending on the system and purpose of livestock farming, offtake rates and stock numbers. The highest values in the northern central areas of Namibia are largely a consequence of this area having high stocking rates of cattle, which produce beef that can be exported because they are south of the veterinary cordon fence.

Photo: C Begley

A large proportion of Namibia is under rangeland. The southern regions are mostly stocked with sheep and goats, whereas cattle are more commonly kept in the northern and central areas. The ecosystem service in this case is the land’s contribution to livestock production through the provision of forage and water because almost all production is on large farms or areas of communal land, rather than in sheds or feedlots. The production value is realised from the sale of meat and skins, whereas other values come with savings and the capital value of livestock.

10.18 Estimated value of nature-based tourism, 201921

Tourism has been the fastest-growing economic sector in Namibia in recent decades, and one of the most valuable in terms of its contribution to the economy and to employment. This is especially important in rural areas where sources of income are limited. Renowned as Namibia is for its magnificent scenery and abundant wildlife, nature-based tourism is the most important component of the tourism sector. This includes outdoor activities such as hiking, biking, wildlife safaris and photography, birdwatching and adventure tourism.

Tourism made a direct contribution of 8.4 billion Namibian dollars to the country's gross domestic product (GDP) in 2019. Much of this value was generated in protected areas (42 per cent) and on communal land (35 per cent). Coastal areas and privately owned land, including game farms, account for the remainder. Tourism values of freehold lands were highest around protected areas.

Wildlife and tourism is second to mining in its value to the national economy, surpassing agriculture and marine fish production. Surprisingly, there is no methodical or periodic accounting system in place to measure the value of Namibia's tourism and wildlife.

Namibia's tourism industry virtually collapsed during 2020 and 2021 when COVID-19 swept across the world. Great numbers of jobs were lost, many families lost their only source of income, countless formal and informal businesses closed. Happily, tourists returned in substantial numbers to Namibia in 2022.

Photo: JB Dodane

Wide, open landscapes are one of the country’s characteristics, especially in southern and western Namibia. Here, the Namuskluft Mountains tower over an otherwise flat landscape in southern Namibia; they are not far from the magnificent Fish River Canyon, which cuts down deeply into the landscape and is a major attraction to tourists. Other areas that generate substantial value from tourism are in and around protected areas, particularly Etosha and the Namib-Naukluft national parks where tourists visit various other local attractions. Other popular destinations are the coastal towns and surrounds of Swakopmund and Walvis Bay, and Waterberg, Bwabwata and Nkasa Rupara national parks.

10.19 Overall income from communal area conservancies, 1998–201922

The total cash income and in-kind benefits generated in conservancies grew from less than 1 million Namibian dollars in 1998 to more than 152 million Namibian dollars in 2019. This includes all directly measurable income and in-kind benefits.

Community forests do not generate income through tourism or hunting, but some community forests provide income to residents through the sustainable harvesting of thatching grass and other indigenous natural products such as devil's claw (Harpagophytum procumbens).

The generation and diversification of incomes in communal areas where there are few other means of earning cash has been one the most significant benefits of Namibia's conservancies. Most income is generated from the sale of game meat and wildlife trophies, the latter organised by professional hunters. Conservancies also run tourism operations, usually as joint ventures with private-sector operators. Other income is from employment at local lodges and from the sale of crafts and services. Conservancy funds are used to employ game guards and management staff, and are also distributed to members either directly in the form of cash, or indirectly in the form of social benefits, such as the provision of rural electricity or infrastructure for schools.

Photo: D Cole

Sustainable harvesting of plants such as devil's claw provide an income for residents of various communal conservancies.

Photo: O Ernst & H Baumeler

Trophy hunting is one of the biggest income generators in conservancies