Third period, Gondwana: 550–132 million years ago

The third era in Namibia's geological history begins with Gondwana, a supercontinent comprising all countries in the present-day southern hemisphere and India, that existed for over 400 million years. Namibia was in central Gondwana, and it remained there until Africa and South America split apart 132 million years ago. That is when Namibia started to develop a coastline along what would later become the Atlantic Ocean.

Most rock formations of this Gondwana period stem from two eras. Outcrops from the earlier Karoo Period, between 300 and 180 million years ago, largely consist of Etjo sandstone north of Windhoek, and of glacial and alluvial sediments in southern Namibia. The second, more recent period was associated with the break-up of Gondwana when basalts erupted and intruded between 180 and 132 million years ago.

About 300 million years ago, Gondwana (and Namibia) began to drift northwards again. The climate warmed and melting sheets of ice in the interior turned into rivers that flowed into extensive inland basins and seas in southeastern and northeastern Namibia. Some of the sediments that accumulated in these basins were rich in organic material. Sediments that flowed westwards from central and northern Namibia filled the Paranà Basin of Brazil, a small remnant of which is preserved in Namibia where it is known as the Huab Basin.

Rifts started forming in central Namibia about 240 million years ago. These were early stages of the impending break-up of Gondwana. The most prominent of these rifts are in the Waterberg–Etjo mountain area, from where they stretched northeast into Botswana, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Tanzania and southwest into areas of South America that were then also part of Gondwana. The rifts were filled with coarse sands and muds deposited by ephemeral river systems. Fossils found in these sediments in the Waterberg and Mount Etjo areas have close affinities to others found in South America and East Africa, suggesting ecological linkages between areas that are now very far apart.

Major dune fields developed about 180 million years ago when Gondwana became hotter and drier as it moved northwards away from the South Pole. Remnants of these dunes are still preserved over wide areas of southern Africa. As the rifts reversed direction, their sediments were forced up and are now above ground, exposed as prominent features forming the flat plateaus of the Waterberg and Mount Etjo mountains. Well-preserved dinosaur footprints in the fossilised dunes are found at Otjihaenamaparero near Kalkveld and at other localities in central Namibia, providing an intriguing perspective on what life was present at that time.

Photo: H Baumeler

Fossils, such as this of an aquatic Mesosaurus reptile, and amphibians nearly as big as crocodiles, reflect the diverse and large fauna that lived in the seas and lakes of the Karoo Period in southern Namibia.

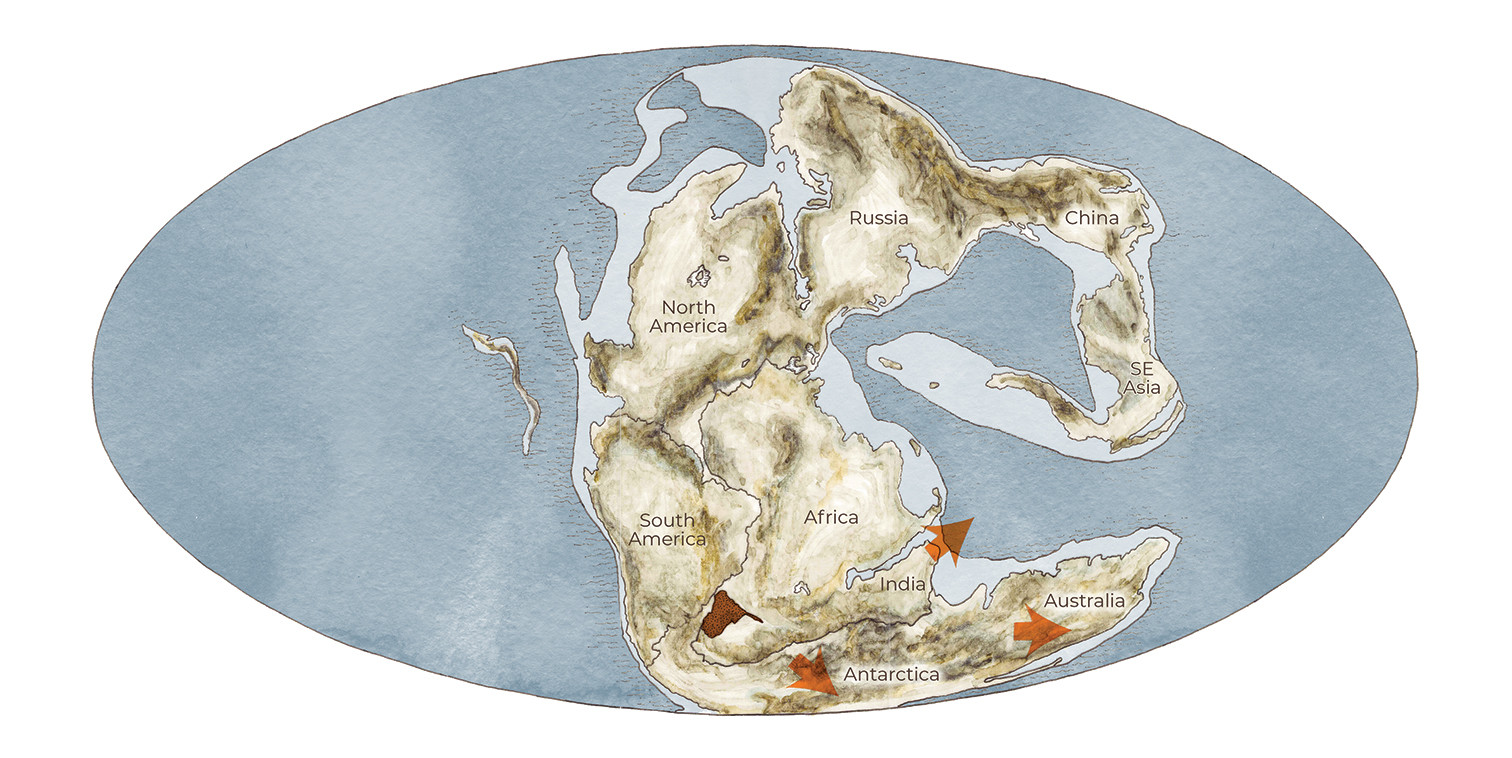

Earth, 315 million years ago:

About 500 million years ago Gondwana started drifting southwards over the South Pole (figure 1.02). Massive continental-scale glaciers covered and scoured much of the surface of Gondwana, including Namibia which was situated in the heart of Gondwana. Over what was later to be southern Namibia, the glaciers appear to have flowed southwards to southwestwards, while those in northwestern Namibia flowed largely westwards into the Paraná Basin of present-day Brazil. Many examples of glacial valleys can now be seen, but the Kunene River is the most outstanding where the striated and polished floors of ancient glaciers still lie some 1,800 metres below the surrounding mountains.

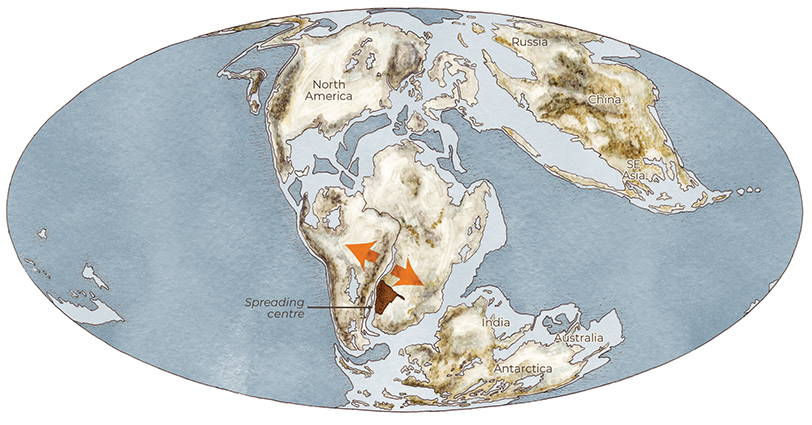

Earth, 180 million years ago:

At about this time, Gondwana started splitting, dramatically, close to the present-day east coast of South Africa. Indeed, Gondwana's original plates have continued to move ever since, evidenced by the continued drifting of South America from Africa, for example.

Photo: R Miller

As Antarctica and Africa began to move apart about 180 million years ago, large volumes of basaltic lavas erupted and covered parts of northern and eastern Namibia (now found in the Mariental and Tsumkwe areas) as well as over parts of Botswana, Mozambique, South Africa, Zimbabwe and Zambia. These are the rocks that cap and preserve the elevations of the Drakensberg and Victoria Falls. Some of the magma that did not make it to the surface was intruded as large sills, and now form these blocks of dolerite that decorate Giants' Playground near Keetmanshoop.

Photo: O Ernst & H Baumeler

More dune fields developed as Gondwana warmed as it moved away from the South Pole. These dunes covered over one million square kilometres, larger than Namibia's surface area today. They were still active at the time of the Etendeka volcanic eruptions, which covered and preserved large areas of dunes in situ. Studies of the preserved dunes have confirmed that this was an extremely arid period, and that the dunes were formed by wind that blew predominantly from the southwest. In places, such as here about 20 kilometres west of Twyfelfontein, darker Etendeka basalts lie directly on top of the paler dune sandstones, exactly where the erupting lavas cooled and solidified 132 million years ago.

When South America and Africa started to part ways 132 million years ago it caused one of the world's largest known volcanic eruptions. Lava flows from this period have been discovered in Uruguay, Brazil, Angola and Namibia where they form the distinctive flat-topped Etendeka hills of Kunene Region. This, however, represents only seven per cent of the total area covered by these lavas, the rest being in South America. The dominant lava flows were liquid basalts produced by relatively quiet eruptions. But many were more explosive, generating huge volumes of magma.

While these lavas erupted, intrusions also pushed up into the earth's crust, cooling slowly, but remaining below the surface. These have now been exposed by erosion, giving Namibia many of its iconic landmarks and inselbergs, such as the Brandberg, and Erongo, Paresis and Okonyenya mountains and the Spitzkoppe.

Photo: H Dillmann

Doros Crater is not a crater formed by an erupting volcano, but by an igneous intrusion that pushed up during the split of Namibia from South America. It slowly cooled and hardened, becoming visible on the surface only after the surrounding, softer landscape eroded away.

Earth, 132 million years ago

Africa and South America start to split. Massive flows of lava exuded from the earth covering many hundreds of thousands of square kilometres. Brandberg and other igneous intrusions pushed up to below the surface.