Minerals

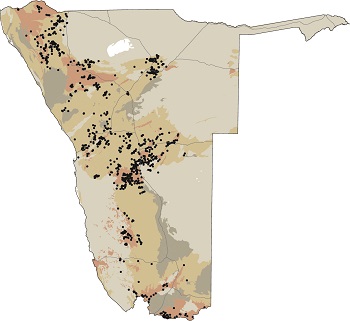

Although minerals are just compounds within rocks (or sand), some are rare while others have distinctive characteristics, and are of economic interest. Understanding how the compounds form and where they may occur requires a sound understanding of how different rock types are formed. Ore deposits can form in a multitude of environments including several igneous systems, during metamorphism, and during sedimentation and burial. This also means that if a particular ore deposit is found in one area it is likely that similar ore bodies will be found in the same geological or tectonic units elsewhere. The maps in this section also show how different minerals are often found in clusters in Namibia. The majority of active mines are in these clusters.

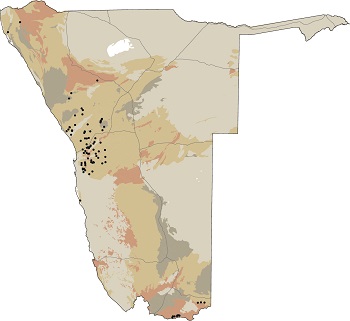

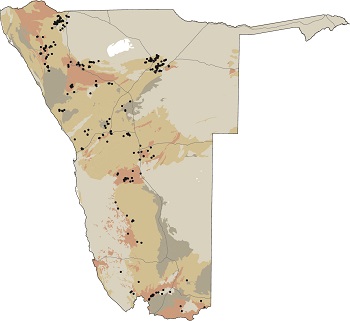

2.21 Mineral deposits20

Almost all mineral deposits known in Namibia are found where rocks are exposed in the western half of the country. No significant bodies of ore are known in the geologically young cover of sands in the east or in the Namib sand dunes. However, many of the bedrock formations found in the west are known to lie beneath the younger deep cover of sands, and so it is expected that there are more deposits under the Kalahari sands. One challenge for the future is to explore below the sands using new geophysical techniques.

Photo: H Baumeler

Marble, granite, conglomerate, sodalite and dolerite are the main types of dimension stone extracted in Namibia, most of which is exported. This aerial photo shows Marmor, a marble mine near Karibib.

2.22 History of mining21

This map shows mining licences in Namibia in 1914, but Namibia has a much longer history of mineral exploitation. The oldest evidence for processing metal ore is from Iron Age archaeological sites in the vicinity of the Okavango River in northern Namibia. More recently, copper was smelted from relatively high-grade surface ores in the Rehoboth area and along the Kuiseb River near the Matchless Belt of amphibolite. These ores were first processed to make beads around 400 years ago. The copper ores alerted German colonists to the mineral potential of the territory, and exploration companies were soon set up.

The first geological maps were produced in the 1880s and this aided the identification of further ore deposits. By 1891 maps had appeared showing mineral deposits of many types. However, the major game changer in Namibian mining came in 1908 with the first confirmed discovery of a diamond in southern Namibia. A rush for diamonds began and the German administration at that time felt compelled to institute regulatory measures to contain the frenetic activity that ensued. More than 110 years of continuous mining later, diamonds are still a major source of revenue for Namibia.

Photo: JB Dodane

Salt has been harvested for hundreds of years from pans east and west of the main, large Etosha Pan. Much of the salt was for local consumption by Aawambo in the Cuvelai, but salt, ivory, slaves and ostrich feathers were the first major trade exports from the Cuvelai. In recent years, salt is mostly produced from purpose-built saltwater evaporation pans at Walvis Bay, Panther Beacon (just north of Swakopmund) and Cape Cross.

2.23 Diamonds

All the known diamond deposits in Namibia are sedimentary, originally derived from kimberlites in the interior of South Africa, Botswana and Lesotho from where they are carried down the Orange River and then northwards along the coast.

The diamonds are sorted initially by the waters of the Orange River and then by the Atlantic Ocean. Only well-formed diamonds reach the coast, because those with weaknesses disintegrate as they are swept down the rocky and turbulent Orange River. The diamonds are pushed into the Atlantic Ocean and then swept northwards by the longshore drift of the Benguela Current. The drift effectively sorts the diamonds with the majority and heaviest of them being deposited in the south, close to where the river spills into the ocean. The central area of coast – known as the diamond gap – has very low concentrations of diamonds. This is thought to be a consequence of the shape of the shoreline and the direction of the current. The origin of diamonds reported in the Kunene River is not known.

Photo: MODIS image, National Aeronautics and Space Administration

Seen here is the Orange River in flood and spilling into the Atlantic Ocean with its plume of sediment. The Orange River essentially sorts and conveys high-quality diamonds from the interior of southern Africa, depositing the gems offshore on the continental shelf. The waters are shallow enough for strong ocean swells with waves of more than five metres to carry the diamonds (and other sediments) back towards the coastline north of the river mouth. The Benguela Current then carries them northwards and onshore from where strong southwesterly winds may move the diamonds farther.

Photo: J Jurgen

Most diamonds deposited like this on Namibia's coast have been recovered by miners armed with diverse machinery that dredge, sieve, sweep, scour and sort the coastal sediments. While in the early 1900s diamonds could simply be picked up off the ground, returns along the coast have gradually diminished. Most mining nowadays is thus done from ships that dredge the floor of the continental shelf. Jointly, kimberlites in central southern Africa, the Orange River, the Benguela Current and industrial mining have provided the Namibian economy with a great deal of revenue. These photographs demonstrate some of the variety of diamonds recovered in Namibia, ranging between large diamonds found in the lower Orange River and the assortment of small diamonds recovered north of Terrace Bay.

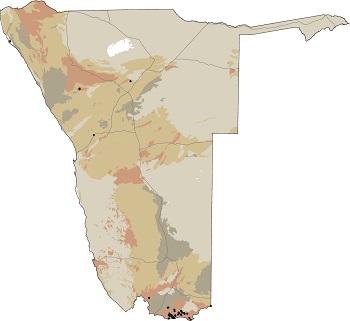

2.24 Uranium

Uranium ore deposits are focused largely in the central-western areas of the country, and the three uranium mines that have been developed in Namibia to date are all in this area. The ore deposits are found as two broad types: primary igneous ores; and in sedimentary rocks in which the uranium has been derived by weathering and erosion from igneous sources.

Photo: R Miller

Uranophane crystals in a granite at the Rössing Uranium Mine. These radioactive yellow crystals are formed from other uranium-bearing minerals.

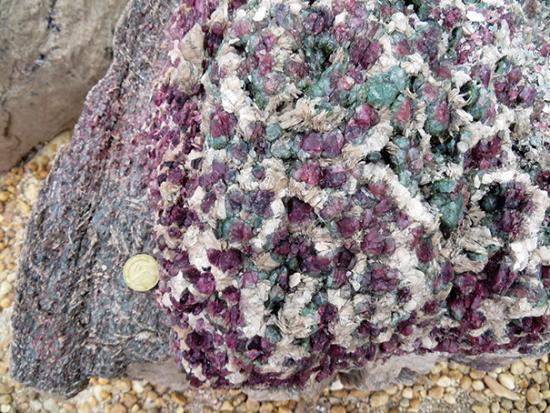

2.25 Rare earth elements and carbonatites

Recently, deposits of rare earth elements have received considerable interest, as they are important components in mobile phones, batteries, wind turbines, night-vision oculars and a host of other devices. Rare earth elements are found either in carbonatite rocks or pegmatites, both being unusual igneous rock types, and of which there are several deposits in Namibia.

Photo: R Miller

A pegmatite from Otjua. The lowest layer is cleavelandite, then finegrained pale blue tourmaline, followed by a coarse-grained pink and green tourmaline with white cleavelandite. The N$1 coin provides a scale.

2.26 Copper

Copper is the most widespread of all commercial minerals in Namibia, yet distinct clustering or 'mineral provinces' for copper are still recognisable. In many cases the deposits are too small to mine, but the clustering of deposits tantalisingly suggests that large undiscovered deposits may exist in those areas. Colonists first exploited a copper deposit in Namibia as early as 1857, but the deposit that was later to become Tsumeb Mine had long been known to local people before this. Large-scale mining of copper in Tsumeb started in 1906.

Photo: R Miller

Green copper mineralisation, Kalahari Copper Belt near Dordabis.

2.27 Gold

Gold was first discovered in Namibia in 1899 with many small deposits being found. But only the small Ondundu deposit northwest of Omaruru produced notable quantities of gold from 1924 to 1963. Gold mining resumed in earnest in 1990 when Navachab Mine at Karibib started production. This was followed by the development of Otjikoto Mine south of Otavi, which started production in 2014. Both mines have exceeded their production targets and exploration continues.

Photo: A Jarvis

Open-cast mining of gold at the Otjikoto Mine between Otjiwarongo and Otavi.

2.28 Zinc and lead

Zinc

Lead

Zinc and lead deposits are often found in association with each other and this can be clearly seen by comparing the two maps showing the distribution of these elements. Much of Namibia's lead has been mined from a deposit at Tsumeb.

Photo: JB Dodane

This is the old shaft of the mine at Tsumeb, a mine that is well known by mineral collectors because at least 243 types of minerals have been described from the mine. Fifty-six were discovered there, some of which have since been found at other localities.

2.29 Tin

Low-grade tin deposits have been known in the Erongo Region since 1908 and small, intermittent production took place there until the 1950s when the industrial tin mine at Uis opened. The mine continued production until 1991 when low prices made its operations unviable and forced it to close. The mine was revived in 2018 and tin concentrate is once again being exported from Namibia. The Brandberg West Mine also produced small quantities of tin ore between 1946 and 1980.

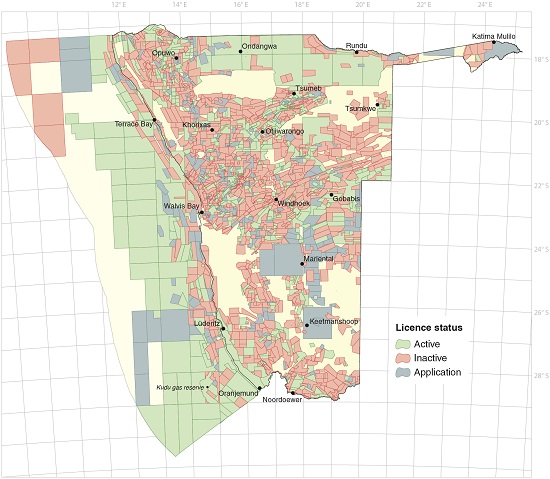

2.30 Petroleum exploration licences, 202022

Petroleum exploration in Namibia began in the late 1960s when the first licences were awarded for offshore exploration. Offshore basins are still the main focus of exploration, but some exploration does take place in older sedimentary basins onshore. The reserves which have been identified in the Kudu gas field are sufficient to power Namibia for at least 20 years, but would be expensive to extract and develop as the reservoir of gas lies more than four kilometres under the seabed and 170 kilometres offshore.