Topography6

Elevations measure the rises and falls of Namibia's surface, which we call its topography. Parts of the country that stand high were once lifted by geological processes and have remained elevated because their rocks resist rapid erosion. Typically, they consist of hard minerals that do not easily disintegrate or dissolve. The oldest rocks in Namibia were formed more than two thousand million ago, and many remain standing proud today having been heated, frozen, pelted, submerged, and pressured at times during their long history.

By contrast, lower areas in Namibia are in places where geological forces once created valleys, rifts or basins. A large part of eastern Namibia was like that, but it is now filled with sediments deposited there by wind or water. This is the Kalahari Basin. Its surface has been levelled by the shifting of sediments into gaps and troughs across thousands of kilometres. The low-lying coastal plain was formed by the breakup Gondwana as Africa and South America spread apart, leaving at first a narrow valley that then widened as the separation grew.

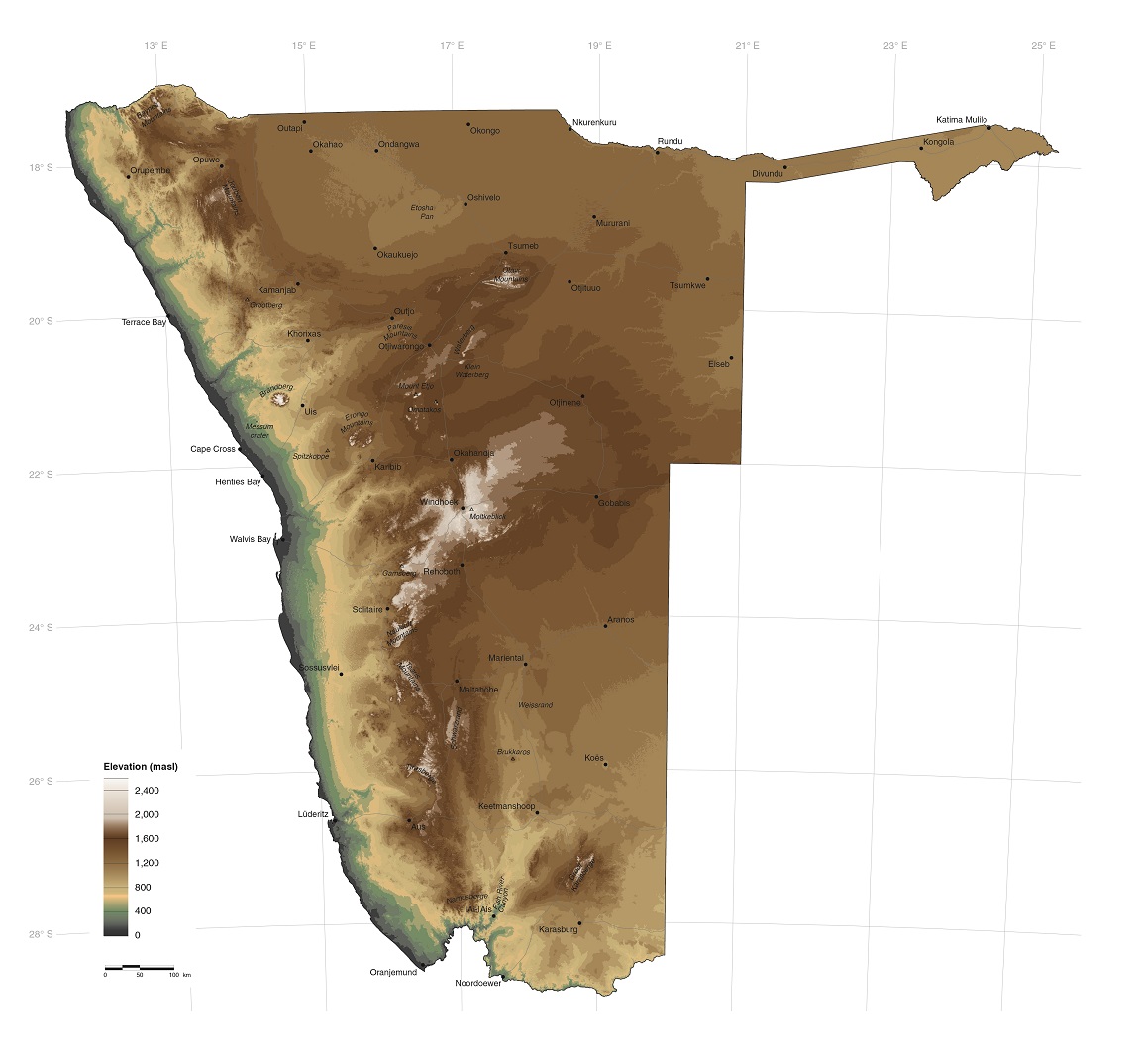

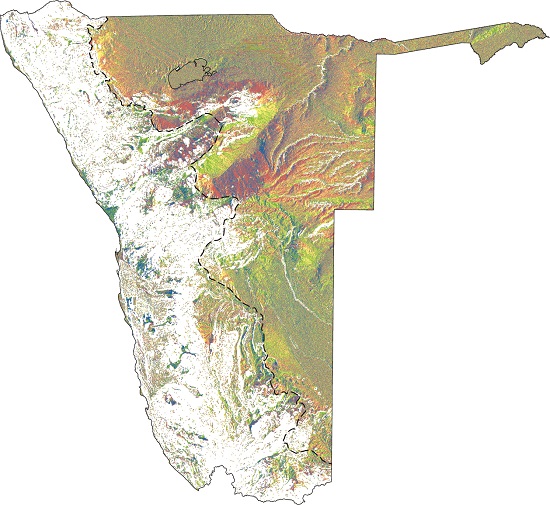

2.07 Elevation

Most of Namibia's peaks are in the centre of the country. Exceptions to this are the Brandberg at 2,573 metres above sea level (masl) in the coastal plain and the Gamsberg at 2,350 metres above sea level which straddles the escarpment. The lower elevations of a rift valley, which stretches north of Windhoek, are visible on the map. Just to the south of Windhoek in the Auas Mountains is Namibia's second highest peak, Moltkeblick (2,479 metres above sea level).

As shown in the graph, 55 per cent of Namibia lies between 1,000 and 1,399 metres above sea level, much of this covering the eastern half and central-northern areas. Only 4.2 per cent of the land lies above 1,600 metres above sea level, and only 8.3 per cent below 500 metres.

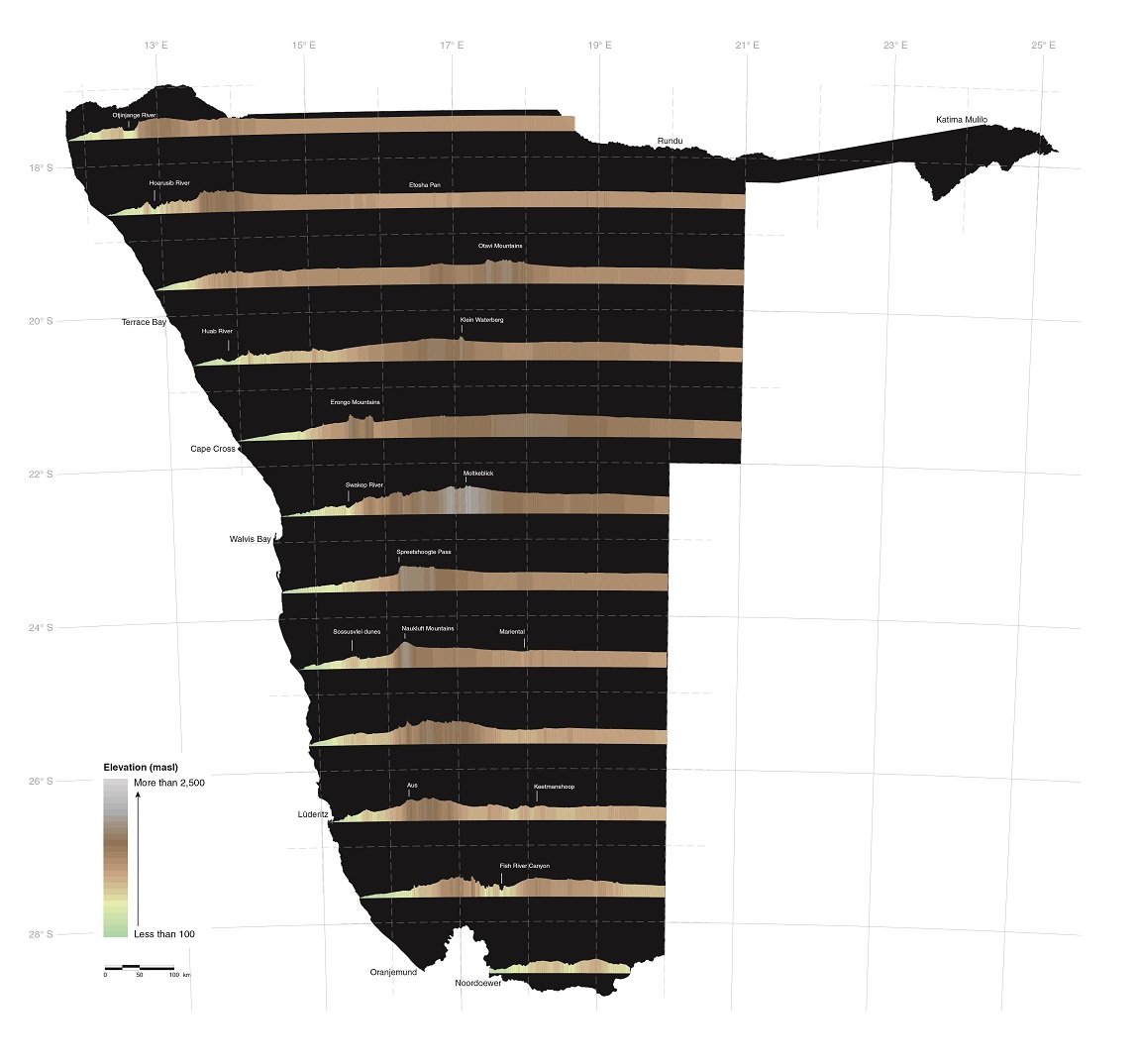

2.08 Elevation profiles6

These profiles show how the coastal plain rises evenly over a distance of 150 to 200 kilometres from the shoreline. The gradual rises continue eastwards in many areas of Namibia, but there are also sharp rises along escarpments in the central areas. Elevations then decrease gradually eastwards across the whole country. The Fish River and its tributaries have carved a broad ravine in the south.

Photo: J Mendelsohn

While much of the Khomas Hochland is hilly and steep, some parts are relatively flat, perhaps having been planed by glaciers.

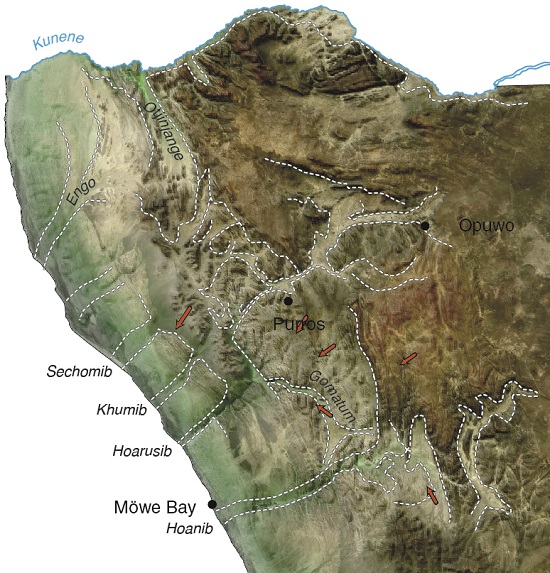

2.09 Glacial valleys

Large valleys shaped by glaciers that traversed northwestern Namibian about 300 million years ago remain visible today.7 One of these is the Hoarusib River valley, shown in the elevation profiles above.

Photo: P Dietrich

Rock surfaces polished and scratched by glacial debris remain in places.

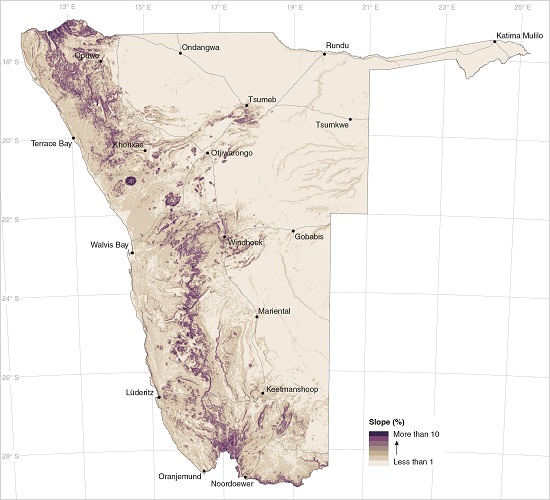

2.10 Slope

Most of eastern Namibia is extremely flat and covered in deep sands. The only small slopes are localised along fossil drainage lines, ephemeral rivers and on dunes. All significant slopes are on rocky land further west; on mountains and hills such as the Brandberg and Erongo, Baynes and Karas mountains; on the escarpment; the Otavi Mountains and Auas Mountains further inland; in deep valleys incised by rivers, such as the Fish River Canyon; and along sections of the Orange, Kunene, Ugab and Kuiseb rivers.

2.11 Aspect of slopes

The aspects, or directions, which slopes face are shown in these maps. Steeper slopes, of one degree or more, which is equivalent to a height change of at least 17 metres over a kilometre, are shown on the first map. Because the slopes are comparatively steep, they tend to face one direction for some distance before being intersected by slopes in different directions. These steeper slopes run mostly from the escarpment to the coast (westward). Half of the slopes of the valleys of large westward-flowing ephemeral rivers typically face northwards and the other half in a more southerly direction.

Gentler slopes (less than one degree) and their subtle aspects are shown on the second map. Most are in eastern Namibia, where the country is relatively flat and covered in sand. Their aspects, in general, vary between facing northeast and southeast as this interior land slopes gently eastwards down towards the centre of the subcontinent (figure 2.01).

Photo: Google Earth and Bing images via Terraincognita, rendered over Shuttle Radar Topography Mission data

River courses can be changed by the slightest change in slope. For example, the Chobe and Linyanti faults along the southern border of Zambezi Region form gentle inclines from north to south. These prevent the Chobe and Kwando rivers from flowing further south. In years when the Zambezi River is very high its water pushes up the Chobe River from their confluence at Impalila Island. The Chobe then flows westward to Lake Liambezi, but also spills over its banks into the Chobe Swamps, which form part of the eastern Zambezi floodplains.

Later, when the Zambezi levels drop, the Chobe reverses its direction to flow eastwards into the Zambezi. The Chobe is indeed a river that flows in two directions! The sharp line between the Zambezi floodplains in Namibia and the woodlands in Botswana marks the position of the Chobe Fault. Other geological faults in this region limit the flows of the Zambezi and Okavango rivers.