Pans, lakes, marshes and springs

Although little surface water is normally visible anywhere in Namibia, there is a great and surprising number of features that hold water at times. These include the tens of thousands of pans that dot the landscape, thousands of springs that bring groundwater to the surface, and small marshes that spread out from rivers, dams and certain springs. Least of all are Namibia’s only two lakes: the Omadhiya complex of lakes in the central-northern regions and Lake Liambezi in Zambezi.

Collectively, these waterbodies support much life, including plants, livestock, large wild mammals, birds, amphibians, fish, crustaceans, insects and other smaller organisms.

4.11 Springs, pans and vleis11

Pans and springs occur predominantly in eastern and western Namibia, respectively. Most pans are in the flat, sandy landcapes east of the watershed, while the majority of springs are in rocky, steeper areas west of the watershed, which also divides the flows of most ephemeral rivers. In total, about 2,500 springs bring groundwater back to the surface, while approximately 25,000 pans have formed where impervious layers slow the seepage of water into the ground. Most springs and pans do not have names, but many of the bigger ones do, names that are often familiar: Grootfontein, Otavi, Aigams, Witvlei, Etosha, Nyae Nyae and Tsandi, for example.

While Namibia is well-endowed with springs and pans, marshes and lakes are not abundant. Scattered areas of reeds, papyrus and other large aquatic plants form marshes in certain flat areas alongside the Okavango, Kwando and Zambezi rivers, and also form the only substantial marshland in the Linyanti Swamp. Smaller reedbeds also grow in seepage zones close to dams and certain springs.

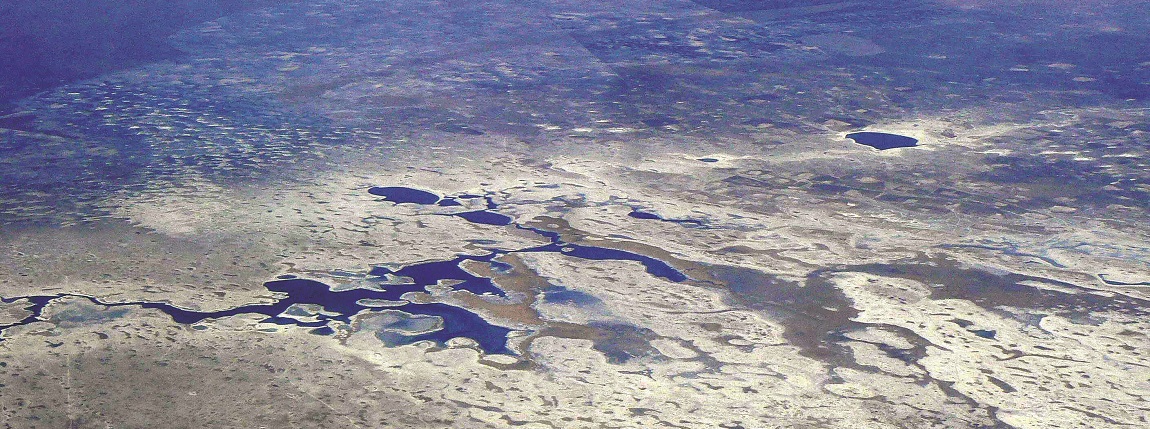

Photo: NASA astronaut image

Namibia's largest pan, Etosha, was once a vast lake extending north of the border into Angola, and was fed by the Kunene River. Through river capture processes several million years ago, the Kunene's watercourse was diverted westwards along its present route to the Atlantic Ocean. Nowadays, most water in Etosha Pan comes from local rain or from flow along the Ekuma River from the Cuvelai drainage system or flow along the Omuramba Owambo. An astronaut in a space shuttle took this photograph looking west across Etosha towards the Atlantic Ocean in the background. Other pans lie along the Atlantic coast. Like Etosha, these are saline pans, their salt having been carried onshore by sea breezes. Etosha's salt accumulated from minerals carried down the Cuvelai drainage system in water that then evaporated. Other saline pans are clustered around Etosha.

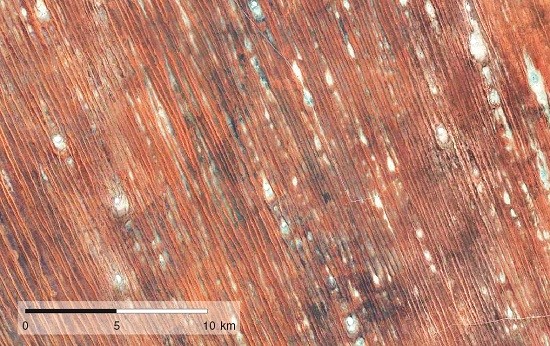

Photo: Sentinel image, European Space Agency

Hundreds of pans fill around Tsumkwe in years when rainfall is above normal. The best-known of the pans is Nyae Nyae, although all the pans in this area are often collectively called by this name. When flooded, this concentration of wetlands supports an extraordinary abundance of life made possible by rich supplies of soil nutrients that have accumulated during the preceding dry years. With accumulated rainwater, dormant eggs, seeds, pupae and spores then hatch and emerge, creating a great supply of frogs, insects and other invertebrates that attract tens of thousands of birds to feed and breed. Indeed these pans may be one of the most important breeding areas in Africa for various species of grebes, crakes, rails, ducks, geese, moorhens, gallinules, terns, herons, egrets, storks and snipe. Where many of these birds live at other times is a mystery, however. [19.74˚ S, 20.53˚ E]

Photo: Google Earth image

Thousands of pans lie sandwiched between dunes in all the active and inactive dune fields in Namibia. The white pans visible here lie in interdune valleys around Aranos and Gochas in the eastern and southeastern areas of the country. Most of these pans are underlain by saline soils and very seldom have water. However, when heavy rains fall many waterbirds are attracted to feed on the tiny crustaceans that then hatch from eggs that have survived for years, perhaps decades, in the pans' salty sediments. [24.86˚ S, 19.29˚ E]

Photo: P Lambrecht

Pans in Namibia are found predominantly in areas with very shallow gradients and are formed through successive processes of ponding, leaching and evaporation. Salts in the soils dissolve and accumulate over time in the shallow depressions; the salts help solidify the pan surfaces.

Photo: J Mendelsohn

Photo: Sentinel image, European Space Agency rendered over Shuttle Radar Topography Mission data

Although both the Omadhiya lakes (top) and Lake Liambezi (bottom) fill temporarily, they have very different characters. Liambezi is largely supplied by the Bukalo Channel from the Zambezi River and backflow of the Chobe River. The lake was reported to have water in 1879, and then filled again during the 1950s. It was dry from 1985 until the summer of 2005/06, when it filled again and remained a lake until 2014. The lakes of the Omadhiya system hold water more frequently and regularly. Their water is supplied by channels of the Cuvelai drainage system. One of its lakes – Lake Oponono – gets its water from the Etaka Canal, which is probably an ancient channel of the Kunene River. Both Liambezi and the Omadhiya lakes support large commercial fisheries at times.

Photo: J Mendelsohn

While the Linyanti is Namibia's only significant swamp, other marshes are found along the Okavango, Zambezi and Kwando rivers and around wetlands scattered elsewhere in the country, including large springs and man-made dams, such as Hardap near Mariental. Parts of Nkasa Rupara National Park (seen here) can support substantial areas of reeds, sedges, lilies and other aquatic plants. In effect, Nkasa Rupara is a delta in bringing to an end the flow of the Kwando River, in just the same way that the Okavango Delta is the terminus of the Okavango River. Both deltas are bounded by geological faults that stem the flow of the rivers. The line of trees in the background grow along the Linyanti Fault.

Photo: M Wenborn

Water in this spring in the Ehi-Rovipuka Conservancy in northwestern Namibia emerges from hills of tufa which are formed from minerals dissolved out of dolomite rocks. Birds, wildlife and livestock depend heavily on this and similar spring waters because there are no other natural water sources in the area.

Photo: J Mendelsohn

This is one of the springs near Okashana on the Andoni Plains just north of Etosha National Park. The slightly brackish water it offers quenches the thirst of many cattle, springbok, blue wildebeest and other animals that graze here in King Nehale Conservancy. The amount of water that gushes out of this fountain hardly varies.

Photo: J Pallett

One of many small springs that bring life to the extremely parched landscapes in southwestern Namibia. This is Kaukasib, a spring southeast and inland of Lüderitz in the Tsau ||Khaeb (Sperrgebiet) National Park.