Perennial rivers

4.02 Namibia's perennial rivers and their upstream catchments2

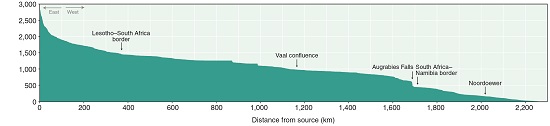

Flowing from west to east in northeastern Namibia are the Okavango (to which the Cuito, another perennial river, merges), the Kwando, and the Zambezi rivers. Flowing from east to west is the Kunene River in the north and the Orange in the south. The Okavango (with the Cuito) and the Kwando end at about 950–900 metres above sea level (figure 4.03). The Okavango ends in the Okavango Delta in Botswana and the Kwando in the Linyanti Swamp in northeastern Namibia, although they may push through to other rivers and wetlands beyond these terminals in years of exceptional flows. The Zambezi River flows on for hundreds of kilometres to the Indian Ocean, while the two westward-flowing Kunene and Orange rivers flow to their estuaries at the Atlantic Ocean.

The Okavango, Kwando and Zambezi rivers flow over the sands of the Kalahari Basin for much of their journeys. This tempers their energy, as do the shallow gradients of their courses. Their flows are slow and meandering, spreading into wetlands along their margins. When it rains, much of the water does not run off directly into these eastern rivers, but instead soaks into the ground, where it permeates slowly, constrained by the gentle gradient, sandy soil and the vegetation that holds the soil in place. Acting like a sponge, the hilly headwaters slowly feed the rivers throughout the year and flatten their peaks of flow. Floods from heavy rainfalls are thus moderated while some flow is maintained during long dry periods. Seasonal peaks and troughs are much less pronounced than those of rivers that come from and along steeper, rockier and denser surfaces, such as the Orange and Kunene.

The upper catchments of the Kunene and Okavango rivers are close to each other on Angola's Central Planalto, and they carry about the same total volume of water each year. Yet the Kunene's westward flow is over shallow soils and rocky ground and is more volatile than that of the eastward-flowing Okavango which is moderated by its gentle gradient and sandy sponge.

4.03 Elevation profiles of Namibia's perennial rivers3

| Zambezi* | Kwando | Okavango | Kunene | Orange | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altitude at headwaters (masl) | 1,476 | 1,291 | 1,753 | 1,729 | 3,300 |

| Altitude at base level (masl) | 881 | 931 | 935 | 0 | 0 |

| Length (km) | 1,311 | 1,206 | 1,416 | 951 | 2,280 |

| Average gradient (m/km) | 0.45 | 0.30 | 0.58 | 1.82 | 1.45 |

*Victoria Falls is considered the base level or termination point of the Zambezi for this purpose

These profiles show the elevations in metres above sea level (masl) of Namibia's perennial rivers from their sources: the Zambezi River to Victoria Falls; the Kwando and Okavango rivers to their base levels in the Kalahari Basin – the Linyanti Swamp and Okavango Delta, respectively; and the westward-flowing Kunene and Orange rivers to their mouths.

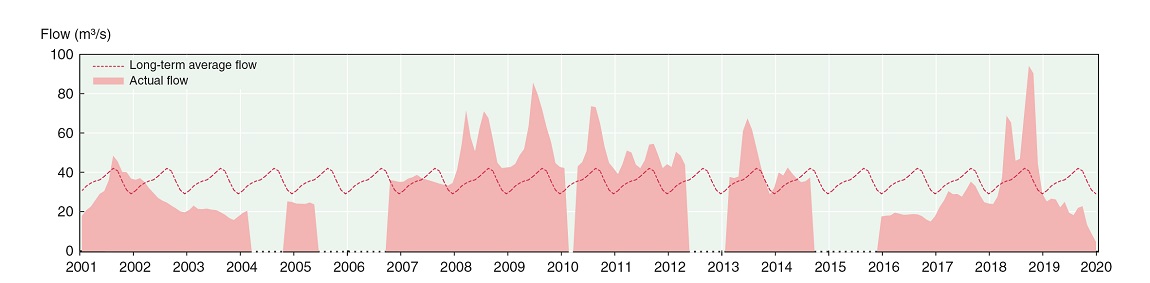

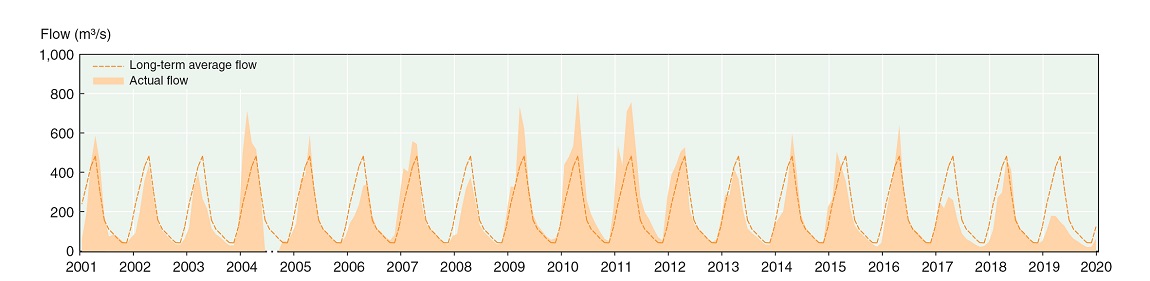

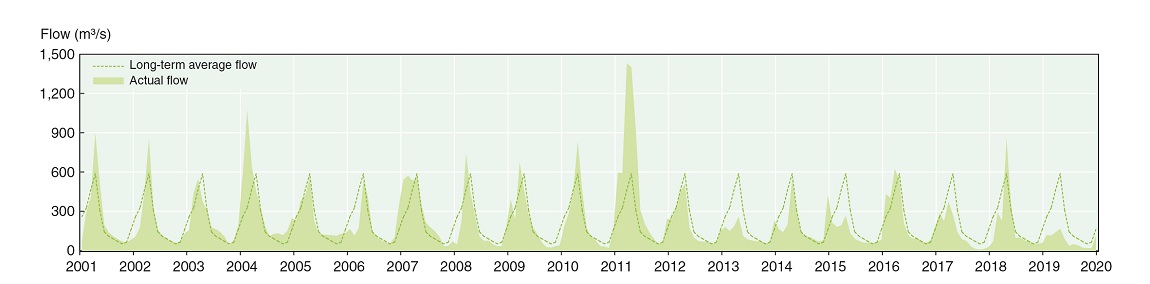

4.04 Seasonal variation in the flow of perennial rivers4

The average volumes of water (in millions of cubic metres) that flow in Namibia's perennial rivers vary throughout the year. The Zambezi dwarfs all of Namibia's other rivers. By contrast, the flow of the Kwando is barely visible above the horizontal axis at this scale. In addition, the Kwando's flow is extremely stable during the year; average monthly flow varies by less than 20 per cent between the months with the highest and lowest flows. The Cuito's flows are also rather steady, only rising and falling Noordoewertwo-fold in an average year. By contrast, average flows along the Kunene, Zambezi and Okavango (as measured at Rundu) in the summer months are many times greater than winter flows. The average monthly flow of the Orange River at Noordoewer shows a less distinct seasonal pattern than expected because high demands on the water of this river system, and the damming of it upstream, have reduced the amount of water reaching its lower reaches and altered its pattern of flow.

Photo: J Mendelsohn

The Kwando is the smallest of Namibia's perennial rivers, and has by far the steadiest flow. It drains deep Kalahari sands, and descends only 400 metres along its entire course. Broad stretches of reedbeds, sedges and floodplain grasslands in shallow water flank much of the Kwando's narrow channel. Ten or more kilometres in breadth, this stable wetland landscape slows the flow of water along its length; large volumes of water are lost to evaporation and transpiration, with the result that the Kwando delivers rather little water by the time it enters Namibia and finally ends its journey in the Linyanti Swamp.

4.05 Flow rates of perennial rivers5

The solid colours on these charts show the volumes of water in cubic metres per second between January 2001 and December 2019 carried by the Kwando at Kongola, the Okavango at Rundu (before the Cuito confluence), the Cuito (its volume is the difference between volumes in the Okavango recorded at Rundu and Mukwe below the Cuito confluence), the Kunene at Ruacana Falls, the Zambezi at Katima Mulilo and the Orange River at Noordoewer. The dotted line indicates the long-term average flow rate at the same points on those rivers. Gaps in the records for the Kwando are due to an absence of data, not an absence of flow. Note the different scales used on the vertical axes. Tick marks on the horizontal axes mark January as the start of each year.

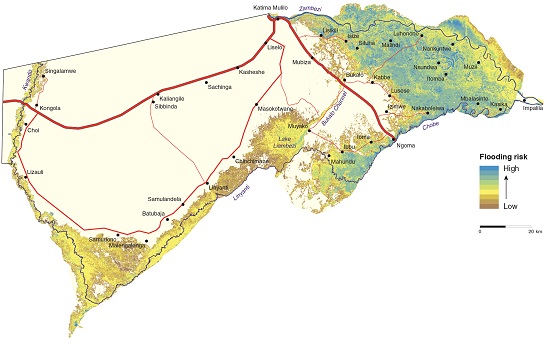

4.06 The frequency and risk of flooding in eastern Zambezi6

The Zambezi river regularly floods across much of the eastern Zambezi Region. Areas close to the Zambezi flood earlier than those close to the Chobe River and Lake Liambezi. The floods usually start in February, March or April and then last for several months. As the water encroaches, people living in the floodplain often leave the area, only to return when the expanses of water have receded. Crops grown in the relatively fertile soils of the floodplains are lost if they are inundated before harvesting. Flooding along the Kwando River and Linyanti Swamp also occurs, but less frequently.

Disruptions to life and the costs of public money spent on evacuation and emergency relief could be reduced if attention was paid to the risks of flooding in different areas, perhaps with settlements being kept away from areas known to flood most often, such as those shown in this map. This assessment of risk was based on floodwaters visible in satellite images taken between 2001 and 2011.

Photo: H Denker

Only small islands remain when floodwaters are at their highest in eastern Zambezi. Although the lives of local people are disrupted, the floodwaters bring many benefits, such as spawning grounds for fish, breeding areas for waterbirds, nutrients to the soils, and fresh green grass for cattle, buffalo, zebra and other grazing mammals.

Photo: Bing imagery

Hundreds of channels, meanders and oxbow lakes formed by floodwaters over tens, perhaps hundreds of thousands of years cover much of the eastern floodplains between the Zambezi River at the top and Chobe River below. Most of the flooding occurs when the Zambezi overflows its banks, from where the floodwaters then spread south.

The Zambezi floodplains and Impalila Island are as far east as one can be in Namibia. The Chobe has no catchment, but fills when the Zambezi is high enough to push some of its water up the Chobe, sometimes as far west as Lake Liambezi. As the Zambezi drops, water in the Chobe River flows back eastwards into the Zambezi River. The Chobe thus has the unusual distinction of flowing both ways. Another special feature is the eastern tip of Impalila Island which marks the point where four countries meet: Zambia, Zimbabwe, Botswana and Namibia. [17.70° S, 25.04°E]