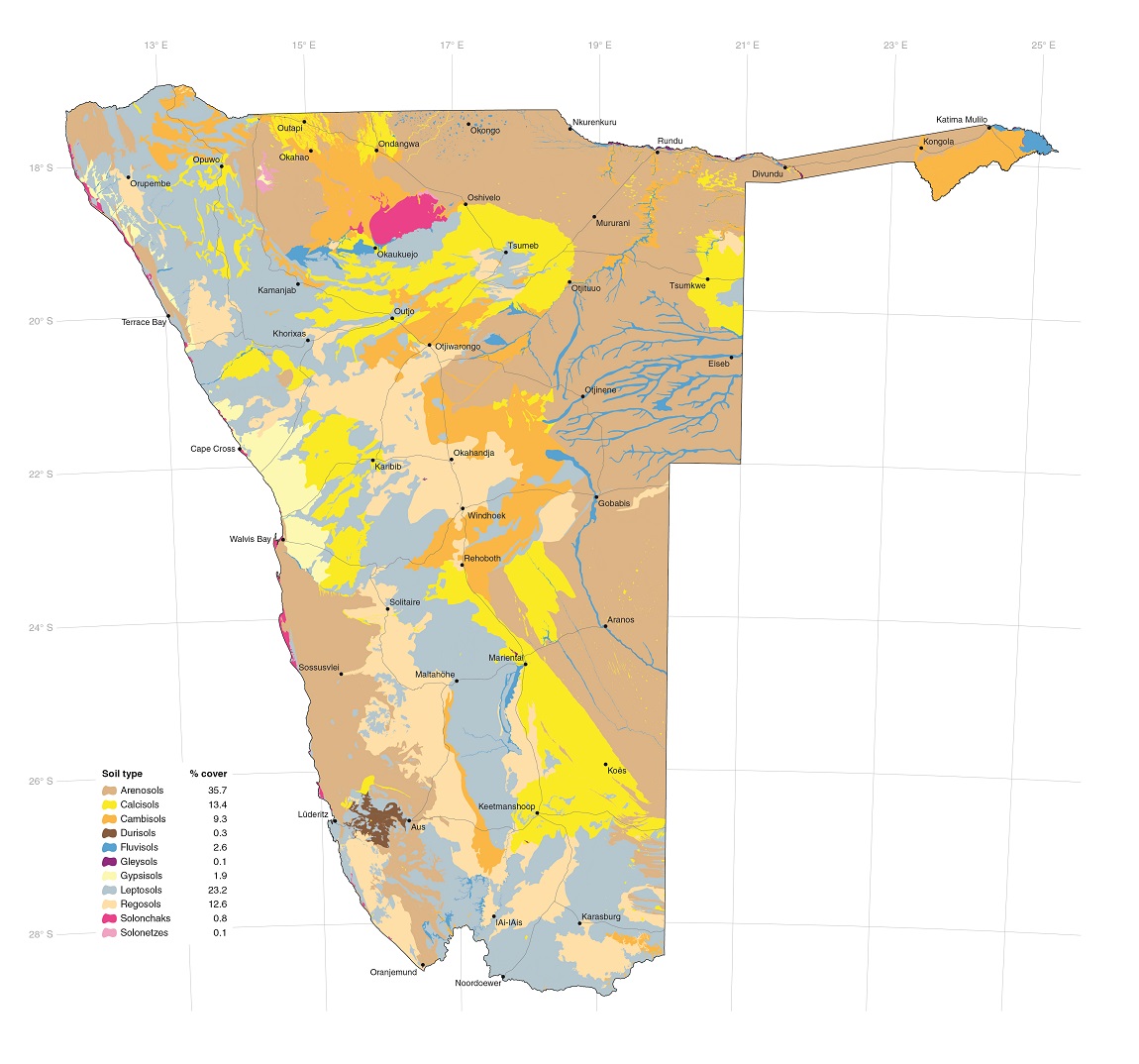

Soil types

5.01 Major types of soil and percentage cover

There are eleven soil types that are relatively widespread in Namibia, and a handful with limited distributions. These soil types can be broadly grouped according to the factors controlling their formation and properties, namely their parent material, position in the landscape, accumulation of substances and age. Firstly, the widely distributed Arenosols are developed in quartz-rich wind-deposited sediments. Dominated by their quartz parent material, Arenosols are resistant to chemical weathering which determines their sandy nature. Vertisols, which have very limited distribution in Namibia, are similarly dominated by their parent materials, but these have been chemically weathered into swelling clays with high nutrient- and water-holding capacities.

Secondly, the shallow Leptosols and poorly developed Regosols, which occur in a broad northwest-to-southeast band across the Namibian interior in association with eroding highlands and escarpments, are formed through weathering of the local underlying rock formations. Fluvisols and Gleysols are found in the lowest landscape positions, such as riverbeds and floodplains. The third group comprises soils typical of arid and semi-arid regions. These are dominated by the accumulation and redistribution of calcium carbonate, calcium sulphate, soluble salts, sodium and silica in the formation of Calcisols, Gypsisols, Solonchaks, Solonetzes and Durisols, respectively. Fourthly, Cambisols are young soils, displaying just the first signs of soil development.

Soils form in two main ways: through the accumulation or deposition of material and through weathering, the essential parts of which are shown in this diagram. Weathering occurs physically when rocks are broken up by collisions, abrasion or temperature changes; chemically when minerals in the rock react with air, water or other chemicals; and biologically when burrowing animals and plant roots expose rock to water and air, or open cracks in the rock.

Over time, solid rock (left) is gradually broken into smaller and smaller fragments and grains of primary minerals. This material (known as regolith) undergoes chemical changes, and is enriched with organic matter to the point where a mature soil with distinct horizons is formed (right). These processes of soil formation and maturity are slowed by aridity and extreme temperatures, and accelerated in wet, humid and moderate conditions.

5.02 Arenosols

Arenosols, in most areas, are deep windblown sands consisting largely of quartz. Their sandy texture and loose, porous consistency mean that Arenosols have a low capacity to store water and nutrients. The Namib Sand Sea, Kunene dune fields and most of the Kalahari in eastern and northeastern Namibia are predominantly Arenosols.

Photo: M Coetzee

Aeolian sands of the Namib Sand Sea form hummocks around plants.

5.03 Fluvisols and Gleysols

Fluvisols are young soils developed in aquatic sediments such as those in riverbeds, river valleys, alluvial fans, deltas, tidal marshes and recent marine deposits. They form with distinct bands varying in texture, colour, organic content and coarse fragments where periodic flooding deposits layers of sediments. Gravelly or sandy material is deposited by fast-flowing water, while fine, silty sediments are deposited by standing or slow-moving water.

Gleysols in Namibia are confined to waterlogged places in rivers, lakes and dams, at the coast and in the Liambezi– Chobe area. They are characterised by greyish, bluish and greenish colours deeper inside the soil mass, with yellowish, reddish or brownish flecks in the upper layers and on the surfaces of aggregates.

Photo: J Mendelsohn

Dark Fluvisols exposed on an embankment along the Okavango River in Kavango East; yellow Arenosols are layered beneath the Fluvisols.

5.04 Leptosols and Regosols

Leptosols are extremely stony or very shallow soils over a continuous rock surface. They are prevalent in hilly areas where the rate of erosion exceeds the rates of soil formation or sediment accumulation. The thin soil layer and rapid drainage mean that Leptosols have low potential for crop production.

Regosols are young, almost undeveloped soils with no diagnostic horizons and little evidence of soil-forming processes. They are found where soil formation has been inhibited by arid conditions or interrupted by erosion or recent deposition of sediments. They are normally medium to finely textured unconsolidated materials common in young sediments. Regosols on slopes are easily eroded due to their unconsolidated structure and prone to desiccation, which limits their potential for cultivating rain-fed crops.

Photo: JB Dodane

Much of western Namibia is hilly and underlain by rock. Regosol and Leptosol soils that characterise these environments are typically shallow and unable to hold much water or support deep-rooted plants such as tall trees.

5.05 Calcisols, Cambisols and Durisols

Calcisols are widespread in Namibia. They are commonly found in arid and semi-arid environments that have distinct dry seasons. They form in alluvial, colluvial and aeolian deposits that are rich in calcium and magnesium. Significant amounts of calcium carbonate (lime) form below the surface where the soil isalternately dampened by rain and dried by evaporation, which concentrates the calcium carbonate into soft masses or layers of hard calcrete.

Cambisols are young soils that show the first signs of differentiating into distinct horizons. They form in recently deposited or exposed colluvial, alluvial and aeolian parent materials, or where aridity or low temperatures slow down processes of soil formation. Cambisols are found in a variety of climates, but are particularly prevalent in arid and semiarid areas.

Durisols have accumulations of silica, which are usually strongly cemented into hardened layers, called duripans. Durisols develop over long periods in old, stable landscapes in arid and semi-arid climates.

Photo: N Pallett

Calcrete nodules, such as these shown here, are typically found in Calcisols.

Photo: M Coetzee

In Namibia, Durisols mainly occur between Aus and Lüderitz.

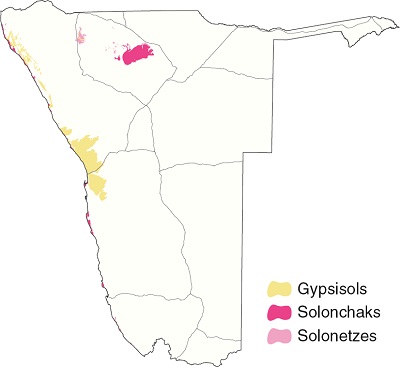

5.06 Gypsisols, Solonchaks and Solonetzes

Gypsisols occur where there is a source of sulphate and calcium to form gypsum – a soft mineral consisting of calcium sulphate – and where evaporation is much higher than precipitation. This is the case downwind of the largest upwelling cells off the Namibian coast where the rising seawater brings organic sulphates to the surface, and southwesterly winds blow them onshore. Gypsisols form where these sulphates are deposited on the calciumrich soils of the central and northern Namib.

Solonchaks are saline soils that occur primarily in coastal zones affected by sea spray, seawater seepage or occasional inundation. They are also found in arid and semi-arid regions where groundwater is close to the soil surface and potential evaporation is much higher than rainfall, and where surface water collects in closed depressions such as in the Cuvelai drainage system’s iishana, the Omadhiya lakes, and Etosha and other pans.

Solonetzes develop in finely textured sodium-rich clayey or loamy soils of former coastal deposits and on flat or gently sloping grasslands with poor drainage. They typically have a brownto- black dense clayey layer rich in sodium just below the surface. The soils have distinctive columns, often covered in bleached, powdery fine sand or silt. Solonetz soils drain slowly and tend to be hard when dry. In Namibia, Solonetzes occur in conjunction with Solonchaks in coastal saltpans and in the Cuvelai–Etosha drainage system.

Photo: S Telm (sdttds, https://www. flickr.com)

Gypsum crystals can occur in many forms in the soil, including as 'desert roses'. These are rosettes formed from interlocking, doubleconvex disk-shaped selenite (a form of gypsum).

Photo: M Coetzee

Solonchaks that are subject to high soil temperatures and repeated cycles of wetting and drying, as from coastal fog, develop a characteristic puffy structure that feels spongy.