Bushfires13

Bushfires have always been a natural occurrence in Namibia, and in much of Africa. However, several factors result in fires having a large, probably unnatural impact on natural vegetation, especially in the northeast. First is the frequency of fires, with many areas burning in more years than not. This gives plants, and especially tree saplings, little chance to grow or recover. Second is the intensity of fires, which kills many plants and wild and domestic animals. Third, is the timing of the fires. The great majority of Namibian fires are started by people, and usually outside periods of the year when lightning would naturally ignite fires. Fourth, few fires in communal areas are controlled. Individual fires can thus spread far, especially during the driest and windiest times between August and October, reducing large areas to ashes – areas that were not intended to burn when the fires were set.

Most fires are on communal land – especially in the northern regions – where large areas of forest and woodland are destroyed where hot fires occur frequently. These areas then become bush encroached. By contrast, few fires burn on freehold land. Indeed, the absence of hot fires over decades has led to bush encroachment on many freehold farms. Some areas of Namibia thus burn too fiercely and often, others would benefit from periodic intense fires.

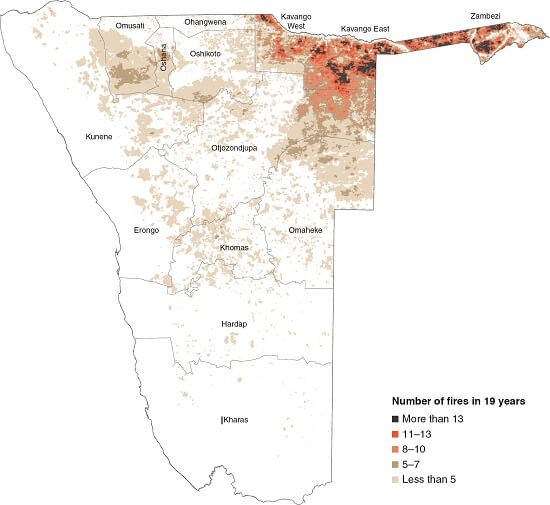

6.17 Fire frequency, 2000–2018

This map shows the number of years that areas in Namibia burnt over a period of 19 years. The highest frequencies of burning were in Zambezi, Kavango East and Kavango West. Within those regions, areas that burnt most often were those where there were relatively few livestock and, as a result, had greater amounts of dry grass available to burn.

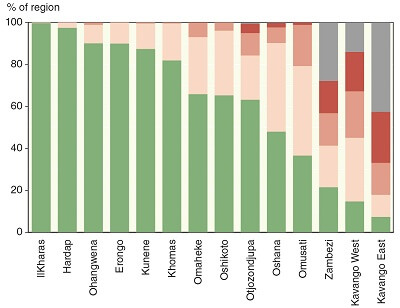

6.18 Proportions of each region that burnt with varying frequency, 2000–2018

The highest frequencies of burning were in Kavango East where 43 per cent of the region burnt 10 or more times during the 19-year period. In other words, nearly half of that region burnt in more than half of the years analysed here. Equivalent frequencies of burning occurred over 28 per cent of the region in Zambezi and 14 per cent in Kavango West. Only very small proportions of Oshana and Otjozondjupa were so frequently burnt.

6.19 Maximum interval between fires, 2000–2018

This map provides a measure of the time that plants can escape being burnt by successive fires. Areas where intervals are short are those where vegetation has little chance to recover before it is burnt yet again. Young trees are killed most easily by intense heat since their protective bark is thin and poorly developed. Saplings in the northeastern areas therefore seldom have enough seasons between fires to grow to a size and height that gives them a chance of surviving. Pioneer shrubs then progressively dominate frequently burnt woodlands with little opportunity for long-lived hardwood trees to recover or re-establish.

6.20 Timing of bushfires, 2000–2018

The great majority of bushfires in Namibia occur between July and October, with most in August and September. On average, burns start earliest in Zambezi where August is the peak month. September is the peak fire month in most other areas, although bushfires in the south and west are most likely in October.

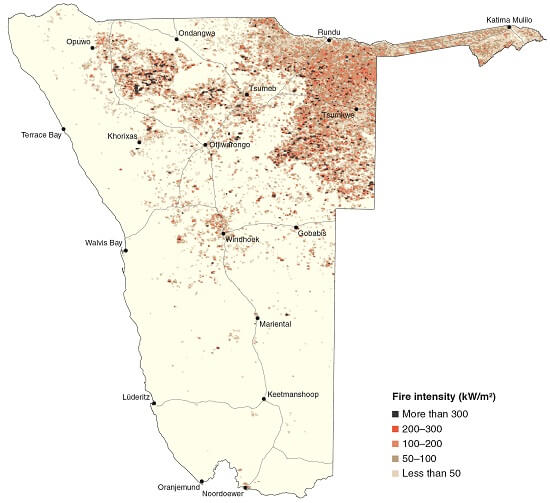

6.21 Fire intensity, 2000–2018

The hottest, most intense fires largely occur in the communal areas of Otjozondjupa, northern Omaheke, Kavango East and eastern Kavango West. Other localised areas where fires are intense are in Etosha National Park, the southern parts of Omusati and Oshana, and north of Mpungu Vlei in Kavango West. Relatively few people and livestock live in these areas, and so there are comparatively large amounts of dry grass to fuel hot fires. The frequency of fires (figure 6.17) perhaps also plays a role, such that areas that burn most often have less intense fires, on average, because less plant material accumulates to fuel the fires. Conversely, fires may be extremely hot and destructive where fires are infrequent.

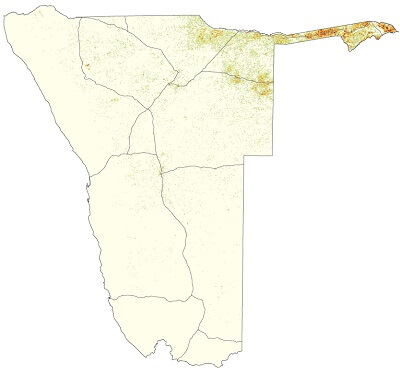

6.22 Density of fire ignitions, 2000–2018

Although much of the northeast burns each year, most fires are started in relatively small areas, such as those in northeastern Otjozondjupa, eastern Bwabwata National Park and on the eastern floodplains of Zambezi Region. Fires started in these areas probably burn relatively small areas, whereas many of those set in other regions burn larger areas.

Photo: MODIS Terra, NASA

Single fires can rage for days and burn hundreds of thousands of hectares, especially during windy periods in years when good rain has produced an abundance of grass to fuel dry-season fires. The dark scar in the image is the area burnt by one large fire over 11 days in Etosha National Park between 6 and 16 June 2012. Another fire in Etosha in September 2011 started on a nearby farm and then burnt 370,000 hectares, killing at least 60 giraffes, 30 rhinos and 11 elephants.14

Photo: J Mendelsohn

Frequent fires gradually kill many trees. This happens in an unexpected way. Prevailing winds from the east often cause small piles of dry leaves to collect on the leeward (west) side of a tree. When next there is a fire, the leaves burn away some of the bark at the base of the tree. Shallow scars thus form in which even more leaves can accumulate over the next season. They then burn, leaving bigger, deeper scars, such as the one shown here. With time, so much of the tree's trunk is burnt that it simply dies or falls over.

Photo: H Denker

Fire has a severe impact on nutrient cycling, in causing the loss of carbon and nitrogen to the atmosphere. Almost one third of carbon dioxide emissions released by grass in the world are produced by fires in African savannas.

Photo: J Mendelsohn

Dense, dry grass cover generally fuels intense fires. When fanned by wind, flames may rise and burn the canopies of trees, leaving a stark landscape of skeletons. Some trees, such as mopane, eventually recover by producing new coppiced growth. But many other trees simply die after being hit by a fire.