Land rights and management

Land in Namibia is either owned by the state, or privately by people or legal institutions (such as companies, trusts and designated authorities). The state owns all unsurveyed land, most of which is communal. The government (as opposed to the state) may be the designated owner of surveyed areas, and it may administer state land and regulate the use of private land. That may seem simple, but ownership is often confused where the land belongs to the state, especially in communal areas. Here, different layers of traditional authorities often claim ownership, as do landholders who believe that they have full rights to land that they have been allocated and occupy.

The ownership of large farms is also sometimes misunderstood in the context of land reform, where farms bought on behalf of the state are allocated – but not given – to private persons. Similarly, select individuals may be allocated or informally acquire large farms on state land in communal areas. In both cases, the question of who owns effective (de facto) or legal (de jure) rights is often equivocal and even contested. These issues go beyond semantics, since ownership governs much of what can be done with land to create wealth or to maintain poverty. It is thus unsurprising that ownership of land is important. Globally, those who own land are comparatively wealthy, while those unable to own land are poorer. About 64 per cent of Namibian families cannot own the land on which they live: 38 per cent of those families live on state-owned communal land; the other 26 per cent live in urban informal settlements on land owned by the local authority.25

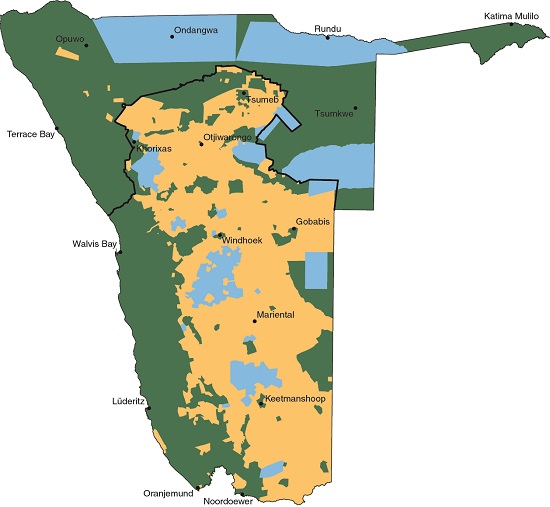

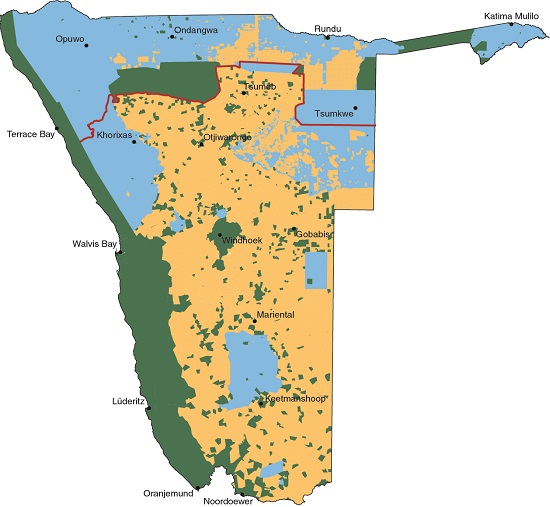

8.19 Land ownership26

The state and its institutions own 58 per cent of Namibian land, contained in the green and pink areas in the map above. The green areas mainly comprise the communal areas, protected conservation areas, and surveyed farms acquired over the years for a variety of purposes, the most common of which is resettlement.27 By 2018, government had acquired 496 farms covering about 3 million hectares for resettlement since independence in 1990.28 The 42 per cent of Namibia not owned by the state (orange) is owned privately, mainly in freehold farms and private nature reserves.

Photo: J Mendelsohn

Tradability determines the value of tenure more than any other quality. Without it, landholders have little or no incentive to invest in the land and its fixtures. Land might then also not be transferable between generations or heirs, and it cannot be used to generate the variety of benefits that other investments offer.

8.20 Land tenure29

Three types of formal land tenure are available in Namibia: freehold ownership, customary and leasehold.30 Freehold ownership is often subject to the approval of government or the local government authority in that area, but the rights to the land are normally secure, and can be inherited and bought and sold on the open market. Private farms and private nature reserves – each often covering many thousands of hectares – are the most conspicuous freehold properties on this map; they are, however, vastly outnumbered by much smaller, urban freehold properties, which are not visible at this scale.

Customary tenure is only applicable to traditional rights that have been registered over surveyed parcels of land in communal areas. The formal registration of these rights began with the promulgation of the Communal Land Reform Act of 2002 (see 8.22 below). Tenure over large areas of communal land is, however, insecure. These are the commons or commonages to which local residents and their relatives have traditional rights of access. While the state may formally own this land, and traditional authorities may manage aspects of access, there are no established tenure rights to control or limit its use. Commonages are therefore largely used on a first come first served basis.

Other than private lease agreements between a lessee and lessor, most leaseholds apply to parcels of communal land used for commercial purposes (shown in green on the map). They also comprise large farms in communal areas that are de facto owned by private individuals, often together with relatives. Government has offered or awarded leaseholds to some of these farms, but tenure is not registered for most of them yet. Presently, these farms may not be inherited, which limits their investment value, and they may not be traded although there is a growing informal market in communal land.31

Tenure in urban areas is varied: local authorities or the state may own much of the townlands, while private people, businesses and institutions have secure ownership of properties they have bought. Residents in informal settlements, however, have no security of tenure.

8.21 Landholdings on communal land32

Freehold properties tend to be ordered, formally registered and clearly documented on maps, survey diagrams and title deeds. Conditions in communal areas and informal urban settlements are usually quite different, mainly because the holdings have not been documented. Local residents normally know the location and extent of boundaries in a neighbourhood, but formal documentation is lacking. That is changing in Namibia where properties in most communal areas are being mapped and registered through the communal land board of each region in Namibia; these are statutory bodies established by government in terms of the Communal Land Reform Act of 2002.33

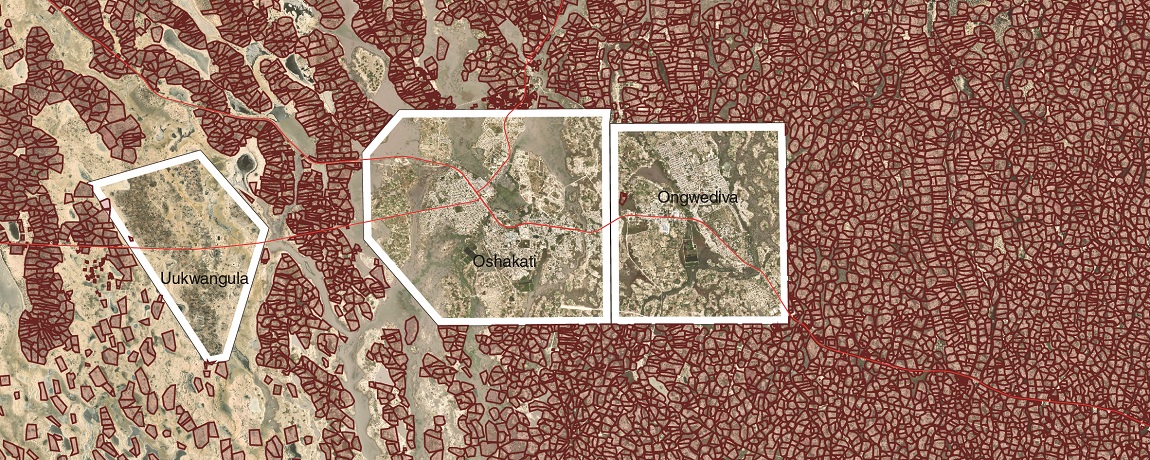

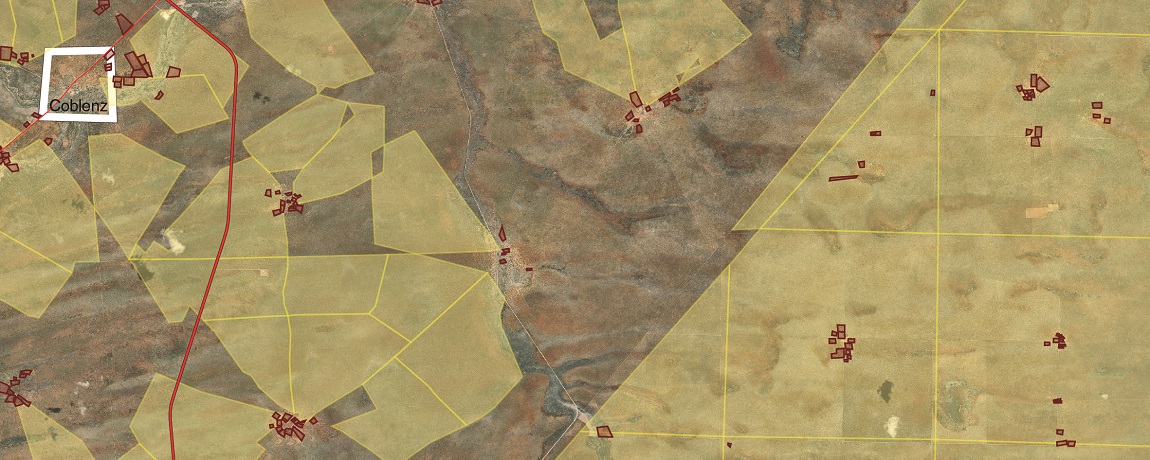

Each of the following four maps show registered customary land rights and large farms over a satellite image; each covers an area of about 550 square kilometres. Some of the maps show unregistered or unknown landholdings mapped by the Department of Land Reform, vividly reflecting the transitional nature of land registration and the formalisation of tenure in Namibia.

The maps show two classes of property: red polygons, each of which marks the boundaries of a private smallholding or farmstead that has been formally mapped by government and probably easily registered as a customary land right; yellow polygons are properties exceeding 50 hectares and require special consideration by the communal land board before their land rights can be registered.

A. Around Oshakati

There is a high density of smallholdings around the towns of Oshakati and Ongwediva and around the settlement of Uukwangula. Unoccupied areas outside the borders of the towns and settlement are drainage lines that flood from time to time. Most of these rural smallholdings cover less than 5 hectares and have been registered as customary land rights. Many of those close to towns are occupied by people who also work in those towns; their properties now produce little food and many have been subdivided into plots of half or a quarter of a hectare and sold.

B. Oshikoto and Kavango West

More than almost any other, this map depicts many of the dynamics and competing interests found in communal areas.34 The regional boundary separates Oshikoto (left) and Kavango West (right). The government allocated two groups of farms to select individuals: before independence, 106 Mangetti farms in former Owamboland were allocated during the 1970s; and after independence, 44 Mangetti farms in Kavango Region were allocated between 1990 and 1995. The map shows some of these farms (outlined in yellow). These early allocations were followed, over the past 30 years, by the appropriation of hundreds of new, large farms in the Owambo and Kavango regions, most of them being at least 2,500 hectares in size. The farms have typically been allocated or appropriated with the agreement of the traditional authorities. Many long-time resident villagers have had their land expropriated and incorporated into these large farms. Most of these farms have subsequently been recognised by the government which has then offered their de facto owners long-term leaseholds. The majority of those displaced are San and other marginalised people who lead rudimentary lives in Kavango East, Kavango West, Ohangwena, Omaheke, Oshikoto and Otjozondjupa.

This map also illustrates the resilient presence of smallholders living and growing crops on relatively fertile soils along interdune valleys. Properties have been mapped and registered through the Oshikoto Communal Land Board bestowing customary land rights to residents. The Ukwangali Traditional Authority, however, has not allowed similar smallholders in Kavango West to register their properties. Other traditional authorities in Kavango West and Kavango East have taken the same stance, in spite of it being in contravention of the Communal Land Reform Act of 2002; they have, however, encouraged holders of large farms to register their land rights.

C. East of Coblenz

There is a great mix of landholdings in the communal areas of Otjozondjupa and Omaheke. Large, neatly bounded, surveyed farms, such as these Okamatapati farms east of Coblenz, were allocated to select Herero farmers before independence. About 90 similar farms were allocated in the Rietfontein area around Talismanus on the Botswana border. Others were established in the so-called Corridor Block east of Aminuis. Many of these farms, and other large pre-independence farms in communal areas, are now occupied by several families who are usually related to the original beneficiary.

Most people in these areas live on small residential plots in villages,35 each of which surrounds a water source with some arable soil nearby. Radiating around the villages are fenced camps, often called bull camps, used to hold livestock when they cannot be grazed elsewhere. At other times, cattle and goats forage further from their home villages. Some village grazing grounds are fenced, separating them from those of neighbouring villages, which in effect create agreed village territories.

D. Former Namaland

Rural residents around the settlement of Kriess live in small villages, each centred on a water point. The parcels of customary land rights are very small; each family having its house, kraals and outbuildings within a hectare or less. Sheep and goats forage near the villages. Once these nearby food sources are depleted, livestock owners who have the means to transport water and employ herders move their animals to distant areas with good grazing and browse. Their animals do well by first foraging in the commons around villages and then by making use of distant food sources that have not yet been exploited. This is another example of the so-called tragedy of the commons, leaving little forage for the stock of owners without the means to move their animals.

» View/download locations map (jpg)

» View/download map - A. Around Oshakati (jpg)

» View/download map - B. Oshikoto and Kavango West (jpg)

» View/download map - C. East of Coblenz (jpg)

» View/download map - D. Former Namaland (jpg)

» View/download legend (for map A) (jpg)

Photo: H Denker

Rudimentary signs such as this one are often used to proclaim occupation over large farms in communal areas. Most areas appropriated for these farms have been occupied and used over hundreds of years by marginalised people who lack recognised tenure, representation or even simple signs to make their land rights known. Without secure tenure, there will always be a risk of losing rights to land. This is the tragedy of the landless, which began when the first farmers settled in Namibia hundreds of years ago.

Photo: J Mendelsohn

Systems to record tenure rights and title deeds are designed for land that has a clearly identified legal person or institution as an owner or tenant. These systems do not accommodate landholdings known in Namibia as villages. These are not simple clusters of homes separated from other houses, as is typical throughout the world. Rather, villages in Namibia are social units consisting of closely related families who normally live near each other. Each village generally has a headman (sometimes a headwoman) who is both the family patriarch (or matriarch) and usually a descendant of the person who established the first home in the area.

Close and not-so-close family members from a village enjoy a range of social capital and tangible capital rights to livestock and land. These kinds of rights find no place in modern, regulated tenure systems. Indeed, such villages, their family members and bundles of rights may even stretch across national borders. Such is the case in this village of Onehova, the northern part of which is in Angola beyond the border cutline that transects the village from east to west. The extent of the village includes the area of fields, almost entirely cleared of shrubs and trees, and the clusters of small buildings.

8.22 Customary land rights in communal areas, 202036

| Region | Registered customary land rights | |

|---|---|---|

| Median size (ha) | Number registered | |

| Erongo | 8 | 5,029 |

| Hardap | 8 | 1,527 |

| Kavango East and West | n/a | 0 |

| ||Kharas | 10 | 2,644 |

| Kunene | 9 | 9,366 |

| Ohangwena | 8 | 28,164 |

| Omaheke | 10 | 2,176 |

| Omusati | 14 | 34,313 |

| Oshana | 12 | 15,704 |

| Oshikoto | 13 | 17,730 |

| Otjozondjupa | 8 | 3,546 |

| Zambezi | 8 | 6,310 |

| TOTAL | 126,509 | |

The Communal Land Reform Act of 2002 made it a requirement that all properties used for domestic purposes be registered to grant customary land rights to residents, a process that requires approval from traditional authorities and communal land boards. The great majority of customary land rights have been registered in Omusati, Ohangwena, Oshikoto and Oshana. High proportions of customary properties have also been registered in Erongo, Hardap, ||Kharas and Kunene. Registration was relatively low in Omaheke, Otjozondjupa and Zambezi. Traditional authorities in Kavango East and Kavango West have not allowed residents to formally register their customary rights over smallholdings, however.

8.23 Administrative regions37

Old magisterial and homeland areas

Namibia has 14 administrative regions (left). Each is administered by a regional council, consisting of a governor and elected constituency councillors.38 Regional offices of the Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Land Reform are responsible for surveying land parcels and the registration of rights to them on communal land, while regional communal land boards adjudicate the applications for land rights.

Prior to independence (right), Namibia was divided into 10 ethnic districts or homelands and 17 separate magisterial districts in areas administered for white and coloured people.

Photo: T Robertson

Four levels of administration affect the use, ownership and management of land. First, the central government sets national policies to be implemented throughout the country; for example, policies and laws for land, conservation and agriculture. The second level comprises the regional governments, which coordinate and manage public services within each region. Local authorities who administer urban areas are the third level. The fourth level of administration governs aspects of land allocation and rights within communal areas. These are the traditional authorities. It is important that all four levels adapt their policies and practices to respond to the changing needs of household economies and the realities of land productivity and potential.

Photo: P Mpimaji (https://commons.wikimedia.org)

Oshakati Town Council, pictured here, is a major local authority in northern Namibia. Local authorities that administer land uses, allocations and rights in urban areas differ in size, autonomy and authority. From the largest to the smallest, these are: municipalities, towns, villages and settlement areas (figure 8.16). Electoral procedures dictate that political parties are allocated council seats based on the proportion of votes they receive, which means that urban residents are not directly or individually represented by elected local councillors.

8.24 Constituencies39

Each region is divided into constituencies. Voters in each constituency elect a councillor to represent them on the regional council. In the past, these regional councillors would elect the governor for their region, but this changed in 2010 when the president gained the power to appoint the governor for each of the 14 regions. Namibia had 95 constituencies in 1992. Recommendations of successive delimitation commissions led the number of constituencies to grow to 102 in 1998, 107 in 2002, and 121 constituencies in 2013. The boundaries of many constituencies and regions are straight lines or follow visible features (roads or watercourses, for example) that do not respect social realities, such as a village boundary or traditional authority area.

Photo: J Mendelsohn

Local traditional authorities headed by chiefs or kings, traditional councils, and then two or more levels of headmen or headwomen administer the allocation of communal land. The appointment of leaders follows hereditary lineage in most traditional authorities, while in others leaders are elected.

The main role of traditional authorities is to allocate land and adjudicate over boundary disputes and the inheritance of land. They often regard themselves as having final authority over 'their' land, which many claim to own. Procedures to acquire land vary among traditional authorities; in some areas, the payment of allocation or purchase fees is required. Other incomes are earned from land through taxes, rents and commissions. Traditional land rights are normally secure and respected by all, but those land rights of weaker social classes may be sold or exchanged for patronage in certain areas.40

8.25 Management of land41

Private individuals, businesses and associations, and institutions of the state, own different parcels of land through various systems of tenure; these areas of land are put to various uses. In addition to these various tenure arrangements and uses is a mosaic of different management entities and systems. Private farms are generally managed by their owners, or by legal bodies such as trusts, companies or closed corporations. There are approximately 12,382 surveyed, freehold and titled rural land parcels in Namibia.42 Many are merged, for purposes of management and economic viability, into larger units suited to farming, hunting or conservation

Government properties are managed directly or indirectly by various ministries, or by state-owned enterprises such as NamWater or NamPower. The Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism manages more state land than any other government agency; these are legally protected areas, Namibia's national parks. The Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism also helps manage conservancies and community forests in communal areas together with locally representative associations. This is one of many instances where the same land is managed, directly or indirectly, by different entities. Another example is urban land, which is managed by local authorities and the owners or tenants of individual properties.

Photo: J Mendelsohn

Namibians keeping and farming sheep and goats in communal areas normally have small homes, such as these on the plains around the Brandberg. Their animals graze around and away from their homes, in areas covering hundreds or thousands of hectares that are shared with the stock of neighbours. No tenure system protects the rights of residents to these common foraging areas.

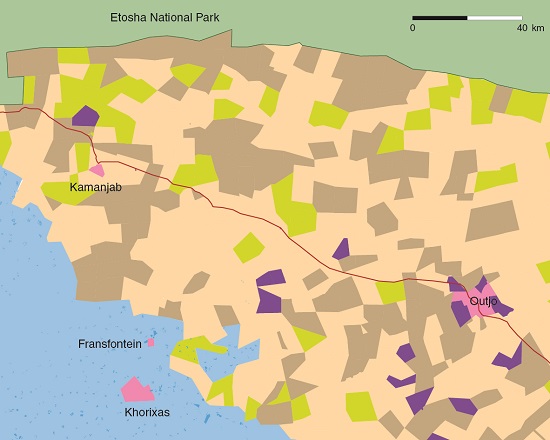

8.26 Farm management in southern Kunene

The national overview of land management provided in figure 8.25 does not fully demonstrate the variety of different management entities, even within small areas of freehold farms as emphasised in this map of farms between Outjo, Khorixas, Fransfontein, Kamanjab and Etosha National Park. Here are large farms that were incorporated into communal land west of Khorixas in the late 1960s; resettlement farms managed by individuals or by resettled groups along lines akin to those in communal areas; and many other farms variously owned and often managed by individuals, businesses, trusts or nongovernmental organisations (NGOs). Developing high levels of cooperation between managers in such a heterogenous landscape is both a challenge and a necessity to manage livestock diseases and wildfires, for example.

Photo: J Mendelsohn

Here at Amarika in southern Omusati, village residents inspect a map to verify applications for customary land rights before they are submitted for registration. Several entities manage communal land:

- People who are allocated land, or appropriate land to themselves, through the use they put the land to and the activities they carry out on it.

- Traditional authorities who are usually involved in the allocation and registration of land parcels and rights.

- Regional government through their communal land boards that are involved in bestowing rights on land, and regional councillors who represent the various constituencies.

- Central government through the Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Land Reform, which sets policy and legislation, surveys the land and registers land rights.

Despite these multiple levels of management, it remains hard to manage land as a safety net for the disadvantaged, as stipulated in Article 17 (1) of the Communal Land Reform Act of 2002 "... all communal land areas vest in the State in trust for the benefit of traditional communities residing in those areas ... in particular the landless and those with insufficient access to land who are not in formal employment or engaged in non-agriculture business activities".

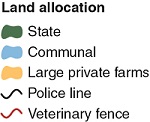

8.27 The expansion of large private farms, 1902–202043

1902

1921

1937

1955

2001

2020

Much of Namibia has been converted into large farms over the past 130 years. The process started in the south in the 1890s during the German colonial period, and continued during South African rule after 1920, and after independence in 1990. Over the same period large parts of Namibia were proclaimed as communal land or 'native reserves'. This process largely stopped with the implementation of the 1964 Odendaal Commission's recommendations, which also ended the division of Namibia between the northern Police Zone and the rest of the country to the south. (The approximate position of the division is shown by the orange line in the 1937 map.) By 1955, about 47 per cent of Namibia had been allocated to commercial farming. A few farms added after 1955 were the last new freehold farms to be sold to white farmers.

The Odendaal Commission made three proposals which led to most of the changes seen by comparing the 1955 and 2001 maps. The first was to establish ten ethnic areas or homelands. The second was to incorporate at least 426 freehold farms considered unsuited to farming into the homelands of Damaraland and Namaland.44 These came to be known as the 'Odendaal farms'. The third, was the major reduction in size of Etosha National Park.

The ethnic areas and other land allocations based on the Odendaal Commission's proposals largely remained in place until independence in 1990. An exception was the surveying of 355 large commercial farms for black Namibians, with a view to supporting their development as commercial farmers. These were allocated in Omaheke in the late 1960s, in Oshikoto during the 1970s, in Kavango East and Kavango West between 1976 and 1995, and in Otjozondjupa in the early 1980s.

The establishment of more large farms on communal lands followed independence, mainly in Kavango East, Kavango West, Ohangwena, Omaheke, Omusati, Oshikoto and Otjozondjupa. All were allocated by traditional authorities or simply appropriated by their new 'owners'. The exact number of farms is not known. However, of the 1,598 farms mapped for registration by 2020, 28 farms were over 10,000 hectares each, 572 farms were between 2,500 and 10,000 hectares, 545 farms were between 1,000 and 2,500 hectares and 354 farms were between 500 and 1,000 hectares in size. These farms cover approximately 3,700,000 hectares.45 The remaining farms were each smaller than 500 hectares.

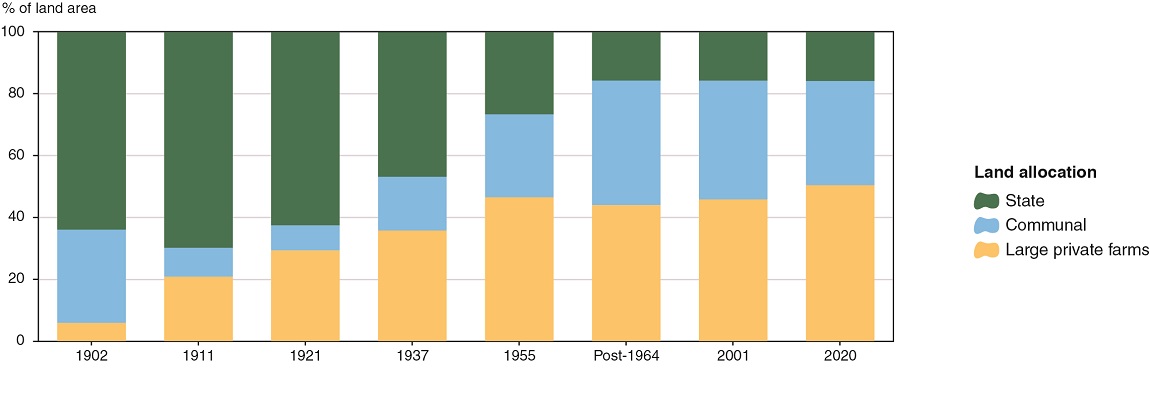

8.28 Areas and proportions of Namibia comprising large farms, and communal and state lands, 1902–2020

| Freehold and large private farmsd | Communal land | State land | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | km2 | % | km2 | % | km2 | % |

| 1902 | 48,100 | 6 | 249,100 | 30 | 526,800 | 64 |

| 1911 | 171,400 | 21 | 77,400 | 9 | 575,200 | 70 |

| 1921 | 241,600 | 29 | 67,100 | 8 | 515,300 | 63 |

| 1937 | 294,900 | 36 | 143,500 | 17 | 385,600 | 47 |

| 1955 | 383,500 | 47 | 221,400 | 27 | 219,100 | 27 |

| Post-1964a | 362,700 | 44 | 332,500 | 40 | 128,800 | 16 |

| 2001b | 377,700 | 46 | 317,500 | 39 | 128,800 | 16 |

| 2020c | 415,700 | 50 | 279,500 | 34 | 128,800 | 16 |

a Representing the early 1970s by when many of the recommendations of the Odendaal Commission had been implemented, which led to about 40,300 square kilometres of freehold farms being added to communal areas.

b Between the early 1970s and 2001 about 15,000 square kilometres of communal land was converted into large farms. The Rehoboth communal area became freehold, and certain small areas were proclaimed as state-owned national parks.

c By 2018, 443 private farms and 53 government farms had been converted into resettlement farms covering about 33,500 square kilometres (of these, about 8,353 square kilometres were converted into resettlement farms before 2001).46 About 38,000 square kilometres of communal land were converted into large private farms between 2000 and 2020.47

d These are freehold farms, large farms recently surveyed in communal areas and resettlement farms, all of which are privately used and controlled, normally by one family.

The maps in 8.27 show how the administrations of Germany and then South Africa spread their influence through the occupation of land by white settlers, which resulted in indigenous pastoralists and hunter-gatherers being dispossessed of the land they used and inhabited. The reversal of that loss of land is at the root of Namibia's land resettlement programme: to transfer freehold land from previously advantaged to previously disadvantaged Namibians. In 2018, of 397,284 square kilometres of freehold land, 70 per cent was owned by previously advantaged Namibians or foreigners; 16 per cent was owned by previously disadvantaged Namibians; 7.7 per cent was allocated for the resettlement of previously disadvantaged Namibians; and 6.3 per cent was owned by government and state parastatals. Beneficiaries were awarded leaseholds for only 172 (35 per cent) of 496 farms allocated for resettlement between 1990 and 2018.48