Ocean currents, upwelling and marine events

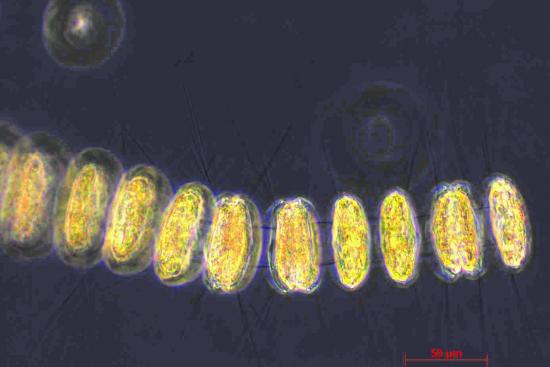

The waters of the cold Benguela Current are tremendously productive. This is a consequence of the wind-driven upwelling that brings a continual supply of dissolved nutrients from deeper waters to the surface. Tiny organisms called phytoplankton absorb nutrients; near the surface, with exposure to sunlight and the process of photosynthesis, these organisms reproduce rapidly, supplying the ocean with an abundant primary base for marine food webs. These phytoplankton blooms cover vast areas of the ocean and are visible from space. Phytoplankton are a source of food for microscopic animals, collectively known as zooplankton. Zooplankton, in turn, provide food to all the higher trophic levels of invertebrates and vertebrates, ranging from benthic creatures, such as anemones, crabs and lobsters associated with the seabed, to shrimps, fish and sharks widely distributed in pelagic waters and air-breathing mammals, birds and reptiles such as seals, whales, dolphins, gannets and turtles and, ultimately, to humans.

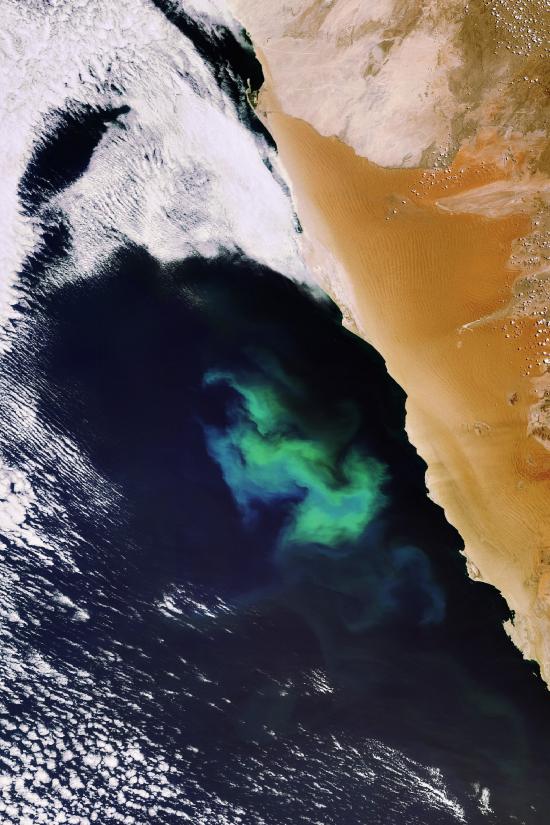

The continual massive production of phytoplankton in Benguela waters, fuelled by powerful upwelling cells along the Namibian coast, not only supports prolific food webs, but also consumes a significant amount of atmospheric carbon dioxide. A large proportion of this abundant microalgal bounty sinks uneaten to the sea floor where it forms soft organic-rich sediments with exceptionally high carbon content. Initial decomposition of this matter by bacteria uses oxygen from the water. When the oxygen is depleted, anaerobic bacteria take over, releasing hydrogen sulphide (a toxic gas) and methane, which build up in the sediments. Sporadically, large amounts of hydrogen sulphide and methane bubble up from the sediments. The hydrogen sulphide quickly reacts with all available oxygen in the water, resulting in severely oxygen-depleted (anoxic) water and microgranules of colloidal sulphur, which create an opaque turquoise colour to surface waters. During these locally named 'sulphur eruptions' so much hydrogen sulphide is released that the foul rotten-egg odour can be smelled on land. The subsequent lack of oxygen in the water, even though short in duration, can cause sea life to avoid the area and fish and other marine animals in the vicinity to die. These eruptions of hydrogen sulphide are characteristic along the central coast of Namibia, where the earliest observers recorded them in the late nineteenth century.

The upside of hydrogen sulphide is that it fuels extensive mats of large sulphide-oxidising bacteria on the seabed. These include the largest bacteria in the world Thiomargarita namibiensis known also as 'the sulphur pearl of Namibia'.1 Not only do these bacterial mats thrive on the sulphidic seabed, but in doing so they detoxify the habitat, and provide food for the small animals living there, which range from a variety of meiofauna (tiny invertebrates) to polychaetes, bivalves, cnidarians, crustaceans and even fish. These bottom-dwelling communities have adapted physiologically and behaviourally to deal with the stressful conditions created by occasional hydrogen sulphide eruptions and anoxia.

Phytoplankton

Photos: A Kreiner

Zooplankton

Photo: Schulz-Vogt et al. (1999). Science. 284. 493-495

Thiomargarita namibiensis, the largest known bacterium in the world, lives in low-oxygen sea-floor sediments off the coast of Namibia and oxidises hydrogen sulphide into sulphur.2

Hydrogen sulphide is not the only cause of lowered oxygen levels in the water. Warm-water events caused by unusually high sea temperatures, or incursions from warm currents, can also result in low oxygen levels. Towards the northern limits of the Benguela Current, intrusions of warm water from the Angola Current cause such events in cycles of approximately ten years. Such conditions can result in a reduction in biological production and the displacement of fish populations from their usual feeding and breeding grounds. Any animals living in the Namibian upwelling system are at some stage challenged by low oxygen – this contributes to the low diversity patterns we see. Some marine animals, such as west coast rock lobster, are particularly sensitive to low-oxygen conditions and when faced with such conditions move inshore in search of oxygenated water where they may become stranded in large numbers and die.

Photo: European Space Agency (ESA)

A bloom of phytoplankton north of Lüderitz photographed from space [Image centre 24.6° S, 13.8° E]

Photo: European Space Agency (ESA)

Red tide in the southern Benguela [34.1° S, 18.7° E]

Photo: G Schneider

Mass mortality of lobsters following a warm-water, low-oxygen event.

Photo: J Paterson

The waters of the Benguela Current support a substantial fishing industry.

The vast quantities of planktonic nutrients introduced from upwelling can also have adverse effects. High chlorophyll content in the water can cause dinoflagellates (a type of phytoplankton that flourishes in calm seas) to proliferate, turning the nutrient bloom toxic and leading to the mass poisoning of fish, shellfish, marine mammals, seabirds and other animals which then wash up on beaches.3 The reddish pigment in some dinoflagellates causes the sea to appear red, which is why these events are known as 'red tides'. Such an event occurred in 2011 along the southern coast.

The anoxic and sulphidic sediments of the offshore shelf of Namibia are considered one of the most inhospitable environments on Earth. Yet despite this, the shelf sustains a remarkable concentration of marine life that has evolved over millennia to cope with these difficulties, and has thrived.4 It is therefore not surprising that Namibia's coastal waters have long been exploited: whaling in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries; a worldwide 'guano rush' to the islands in the eighteenth century; and intense fishing by foreign companies in the twentieth century before independence.

Marine fisheries

The upwellings of the Benguela Current transport nutrientrich waters from the ocean depths to the upper layers where they support abundant fish populations and one of the world's richest fisheries. Almost 500 species of fish are known to occur in Namibian waters of which about 410 species are bony fish and 83 species are cartilaginous fish. Eight species are fished commercially.5

7.01 Distribution of selected commercially valuable marine species6

Hake

Horse mackerel

Monkfish

Pilchards and anchovies

West Coast rock lobster and deep-sea red crab

Two species of hake comprise Namibia's most valuable commercial fish: Cape hake (or shallow-water hake Merluccius capensis) and deepwater hake (M. paradoxus) which are demersal, living on or near the seabed. Cape hake is usually found where the depth is 100–450 metres, while deepwater hake favours areas where the depth is 300–1,000 metres. Cape hake spawn along the central and southern coast, south of 21 degrees south from June–August and February– March. About 97 per cent of the final value of Namibian hake products is derived from exports, mainly to Spain (61 per cent) and South Africa (16 per cent).7

Young horse mackerel (Trachurus trachurus) are generally found close to shore and near the surface, while adults occur further offshore and migrate between surface and deeper waters each day.

Two species of monkfish (Lophius vomerinus and L. vaillanti) occur in Namibian waters, mainly at depths of 300–400 metres. They are slow growing and take about four years to reach sexual maturity. Monkfish are also known as anglerfish because they have an extension to their first dorsal spine that they move like a fishing rod to lure their prey.

Pilchards (Sardinops ocellata) and anchovies (Engraulis capensis) are typically found in shallow waters within 50 kilometres of the coast. Pilchard stocks in Namibia remain at a low level following the collapse of the pilchard fishery in the early 1980s.

West coast rock lobster (Jasus lalandii) and deep-sea red crab (Chaceon maritae) are two commercially valuable crustacean species. West coast rock lobsters are harvested between November and April when they occur close to the shore in water shallower than 30 metres. In winter they prefer deeper waters, up to 100 metres. The rock lobsters are slow-growing, longlived predators that feed extensively on mussels; harvests and their populations have plummeted since the 1970s. Consequently, the fishing industry has increasingly been catching deep-sea red crabs that are found far off the coast at depths of about 300–900 metres.

Photo: J Paterson

On board a Namibian trawler

Photo: O Alvheim

Monkfish

Photo: J Paterson

Photo: J Paterson

By-catch in industrial fishing is a significant cause of mortality of seabirds and is thought to be one of the main reasons for the decline of albatrosses. Of 22 species of albatross, fifteen species are threatened with extinction. The birds get hooked on lines dragged behind longline fishing vessels and drown; they also collide with cables and become entangled in the nets of trawlers. Effective mitigation methods do, however, exist. Since 2015, Namibia's hake demersal-trawl and longline fisheries have been required by law to use bird-scaring lines – colourful streamers that move and scare birds away from the back of the boat. Their use reduced the number of seabirds killed by the longline fleet from about 22,000 in 2009 to about 215 in 2018 – a reduction of more than 98 per cent. In the trawl fleet, the number of birds killed declined from about 7,000 in 2009 to about 1,500 in 2017.8

Marine mammals

Marine mammals in Namibia's waters include the Cape fur seal and 31 species of whales and dolphins. There are eight species of baleen whales, which feed by filtering food such as copepods and krill, and 23 species of toothed whales, including sperm whales, beaked whales, killer whales and dolphins, which hunt their prey. The Sea Fisheries Act (29 of 1992) gives Namibia's marine mammals full protection within the 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone.9

7.02 Distribution of five marine mammals along Namibia's coast10

Bottlenose dolphin

The population of common bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) resident in central Namibia is small, with fewer than 100 individuals. These dolphins grow to over 3.5 metres in length. They regularly feed in association with Cape fur seals.

Photo: H Dillmann

Heaviside's dolphin

Heaviside's dolphins (Cephalorhynchus heavisidii) are endemic to the Benguela ecosystem, and amongst the smallest of dolphins. They tend to stay close to the shore during the day and move offshore to feed in deeper waters (up to 100 metres deep) at night.

Photo: Namibian Dolphin Project

Dusky dolphin

Dusky dolphins (Lagenorhynchus obscurus) are found off South America, New Zealand and the west coast of southern Africa. They range widely across Namibia's continental shelf and are less easily seen from shore than the other dolphin species.

Photo: S Elwen

Southern right whale

Southern right whales (Eubalaena australis) spend the winters off the coasts of southern Africa, South America, Australia and New Zealand and summers in Antarctica. The 19th century whaling industry almost drove the population to extinction but it is gradually recovering and repopulating its previous range. A calf born in Elizabeth Bay in 1996 was the first Namibian breeding record for a century.

Photo: W Bruenken (https://commons.wikimedia.org/)

Cape fur seal

Approximately 60 per cent of the world's population of Cape fur seal (Arctocephalus pusillus pusillus) occurs in Namibia. Although the overall population is stable, there has been a northward shift in its distribution in recent years.

As such, Namibian and Angolan populations are growing while those further south are shrinking. They breed in dense colonies on small, rocky offshore islands and at a number of mainland rookeries.

The five main breeding colonies, in order of size, are Cape Cross, Atlas Bay, Wolf Bay, Cape Frio and Long Island. The seals feed on a wide range of prey including juvenile Cape hake, horse mackerel and pelagic goby, as well as squid, lobster and crab.

Photo: P van Schalkwyk

Coastal birds

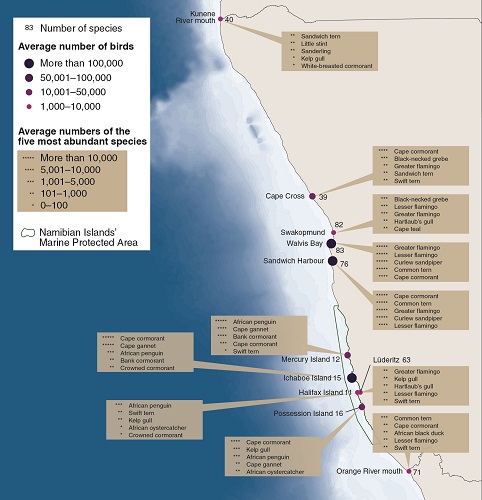

7.03 Distribution and abundance of coastal birds11

The abundance of nutrients, and therefore fish and other marine foods, makes the Namibian coast a rich habitat for many birds. Coastal birds can be divided into three groups: species that breed and roost on islands just off the coast, such as cormorants, penguins, gannets and many gulls; those that forage off the coast but breed elsewhere in the world, such as albatrosses, petrels and shearwaters; and those that frequent estuaries and bays, which provide good feeding grounds to terns and wading birds such as flamingos, plovers and sandpipers.

This map shows the numbers of birds and bird species counted at key sites along the coast between 2001 and 2020. The most important onshore bird sites are the lagoons and bays of the central coast at Walvis Bay and Sandwich Harbour, which each typically host more than 100,000 birds in summer. The islands off the southern coast provide roosting and breeding sites for substantial numbers of cormorants, penguins and gannets.

Other birds that breed along the coast in coastal saltpans and estuaries include waders such as white-fronted sandplover (Charadrius marginatus) and chestnutbanded sandplover (C. pallidus).

Substantial numbers of non-breeding migrant birds from the islands of the Southern Ocean overwinter in Namibia's waters, usually foraging far offshore, and therefore rarely seen. These include up to 750,000 albatrosses, petrels and shearwaters. The ocean to the north of 26.5°S (Mercury Island) is particularly attractive to these birds.12

Photo: J Kemper

African oystercatcher (Haematopus moquini)

Photo: J Kemper

Crowned cormorant (Microcarbo coronatus) and Cape cormorant (Phalacrocorax capensis)

Photo: J Kemper

African penguin (Spheniscus demersus)

Photo: J Kemper

Hartlaub's gull (Chroicocephalus hartlaubii)

Boundless oceans

The oceans change with the seasons and many marine animals migrate great distances to find waters that offer them warmth, protection and food. Migratory marine animals include whales, seabirds (figure 7.56), turtles, and numerous fish species.

7.04 The marathon journey of a loggerhead turtle13

Individual turtles rescued by marine scientists offer the opportunity for attaching small transmitters to their shells to follow their movements. This was the case with a loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta) that was rehabilitated by the Two Oceans Aquarium and released near Cape Town. Over the 26 months that followed its release, the loggerhead travelled 37,000 kilometres, averaging 48 kilometres a day. A turtle navigates the open oceans by sensing the forces of Earth's magnetic field, and finds its way back to the beach where it hatched by recognising the distinct magnetic signature of that particular stretch of coastline. The route shown here was plotted up to February 2020, where the individual possibly returned to its hatching place on the coast of Western Australia.

Similarly, many other marine creatures use Earth's interconnected oceans to travel great distances. A tagged leatherback turtle that was found stranded at Sandwich Harbour in 2008 had been recorded nesting on a Brazilian beach 15 months previously.14

Photo: D Checkley

Five of the world's eight species of sea turtle occur in Namibian waters. The green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas), shown here, rarely breeds in Namibia but individuals have been found on beaches all along the coast and are regularly found feeding in the Kunene river mouth. Leatherback turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) are the most abundant, and are most often seen between Henties Bay and Sandwich Harbour where they feed on the abundance of jellyfish found there. Most sea turtles are considered globally threatened and all are protected in Namibia by the Sea Fisheries Act of 1992.

Photo: H Etter

The humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) is the most common whale seen in Namibian waters. These baleen whales spend summers in the rich feeding grounds of Antarctic waters where they feed on krill and small fish. In winter, they migrate northwards past southern Africa to tropical waters off West Africa where they breed.

Marine conservation

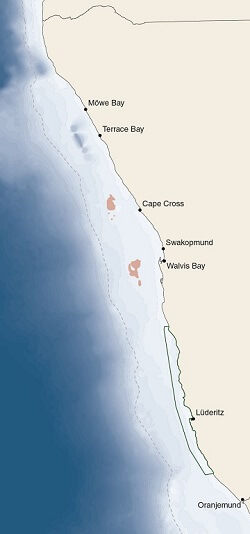

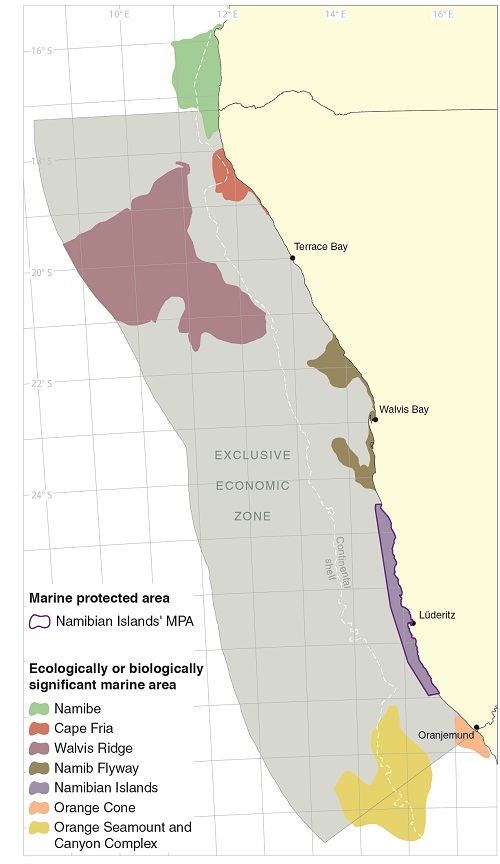

7.05 Namibian Islands' Marine Protected Area and ecologically or biologically significant marine areas15

The Namibian Islands' Marine Protected Area, declared in 2009, spans 1,200 square kilometres along the southern coast; it is approximately 400 kilometres in length and about 30 kilometres wide. The area includes the 14 islands and several additional islets or rocks, some of which seemingly disappear during high tides; these islands and rocks provide sanctuaries to an astonishing variety of marine life. Seabirds and seals dominate the islands' land fauna.

The marine protected area primarily protects seabirds, specifically by safeguarding roosting and nesting areas. Eleven of the 14 seabird species breeding in Namibia breed on these islands and inshore rocks, including Namibia's endangered African penguins and 90 per cent of the world’s endangered bank cormorants. The area also protects the kelp beds around the islands, and important spawning and nursery grounds for fish and other marine resources.

Within the protected area, buffer zones encompass the islands. These zones are subdivided into four levels of protection, which confer strict protection for specified islands, sanctuaries for rocklobster and limit line fishing and harm caused by marine mining activities, most notably diamond mining.

Currently the Namibian Islands' Marine Protected Area is the only formal marine protected area in Namibian waters. However, six other areas within Namibia's exclusive economic zone have been identified as being of ecological or biological significance, and were adopted as such by the Convention of Biological Diversity in 2014. Of these areas, three are transboundary (Namibe, Orange Cone and the Orange Seamount and Canyon Complex) and three are completely within Namibia's jurisdiction (Cape Fria, Namib Flyway and Walvis Ridge). The designation of these areas requires that at least one of seven scientific criteria are met. Namibia’s significant marine areas all meet a number of these criteria as listed in the table below;16 many include interesting marine features (figure 2.02). Protecting these areas through conservation or other management measures would help stop the rapid loss of marine biodiversity in Namibia's benthic and pelagic marine habitats.

| Criterion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ecologically or biologically significant marine area | Uniqueness and rarity | Important life-history stages | Threatened species or habitats | Vulnerable or sensitive species | Biologically productive | Biologically diverse | Naturalness |

| Namibe | H | H | M | M | H | H | M |

| Cape Fria | M | H | H | DD | H | M | H |

| Walvis Ridge | H | H | M | H | M | M | H |

| Namib Flyway | H | H | H | M | H | M | M |

| Namibian Islands* | H | H | H | H | M | L | H |

| Orange Cone | H | H | H | M | M | M | M |

| Orange Seamount and Canyon Complex | L | M | H | M | M | H | H |

| Ecologically or biologically significant marine area | Namibe |

|---|---|

| Uniqueness and rarity | H |

| Important life-history stages | H |

| Threatened species or habitats | M |

| Vulnerable or sensitive species | M |

| Biologically productive | H |

| Biologically diverse | H |

| Naturalness | M |

| Ecologically or biologically significant marine area | Cape Fria |

|---|---|

| Uniqueness and rarity | M |

| Important life-history stages | H |

| Threatened species or habitats | H |

| Vulnerable or sensitive species | DD |

| Biologically productive | H |

| Biologically diverse | M |

| Naturalness | H |

| Ecologically or biologically significant marine area | Walvis Ridge |

|---|---|

| Uniqueness and rarity | H |

| Important life-history stages | H |

| Threatened species or habitats | M |

| Vulnerable or sensitive species | H |

| Biologically productive | M |

| Biologically diverse | M |

| Naturalness | H |

| Ecologically or biologically significant marine area | Namib Flyway |

|---|---|

| Uniqueness and rarity | H |

| Important life-history stages | H |

| Threatened species or habitats | H |

| Vulnerable or sensitive species | M |

| Biologically productive | H |

| Biologically diverse | M |

| Naturalness | M |

| Ecologically or biologically significant marine area | Namibian Islands* |

|---|---|

| Uniqueness and rarity | H |

| Important life-history stages | H |

| Threatened species or habitats | H |

| Vulnerable or sensitive species | H |

| Biologically productive | M |

| Biologically diverse | L |

| Naturalness | H |

| Ecologically or biologically significant marine area | Orange Cone |

|---|---|

| Uniqueness and rarity | H |

| Important life-history stages | H |

| Threatened species or habitats | H |

| Vulnerable or sensitive species | M |

| Biologically productive | M |

| Biologically diverse | M |

| Naturalness | M |

| Ecologically or biologically significant marine area | Orange Seamount and Canyon Complex |

|---|---|

| Uniqueness and rarity | L |

| Important life-history stages | M |

| Threatened species or habitats | H |

| Vulnerable or sensitive species | M |

| Biologically productive | M |

| Biologically diverse | H |

| Naturalness | H |

H = the criterion is met at a high rank; M = medium; L = low; DD = data deficient.

*Formally proclaimed as the Namibian Islands' Marine Protected Area.

Photo: J Kemper

View from Mercury Island towards Spencer Bay and the wreck of the Otavi.

Photo: S Jarvis

Along Namibia's coastline in the cold Atlantic waters, large brown algae (kelp) grow in dense aggregations known as kelp beds. Kelp beds and larger kelp forests are used by a wide range of marine life as a source of food and protection. Globally, kelp forests and the marine life in these ecosystems are under threat from increasing sea temperatures and pollution.