Spatial distribution of selected wildlife species

The arid and variable conditions in Namibia result in patchy resources and unpredictable water availability, and many animals that live here have evolved to cope with conditions such as extreme heat and drought. Some have morphological or physiological adaptations while others have evolved to be nomadic to some extent – with individual animals or large groups evolved to move often, either seasonally or sporadically to follow rainfall or prey, for example, or to spend months or years underground. Habitat fragmentation and demarcation, especially by fences, have restricted the number and magnitude of many of these movements. Wildlife corridors are effective ways to re-establish connectivity. These are narrow areas which connect and allow movement between key areas. The development of wildlife corridors is being explored in some areas as a mechanism to re-establish historic wildlife movements. Studies suggest that medium-sized herbivores can re-establish migrations relatively quickly once physical barriers have been removed.42

Large carnivores

Namibia is proud of its conservation achievements in maintaining the presence of large predators across most habitats, helping to counter the major shrinkage in the global ranges of lion, African wild dog and spotted hyaena in the past 50 years; these are the predators that are least tolerated by livestock farmers. Strongholds for large carnivores are the national parks, particularly Etosha, and the communal conservancies in northwestern and northeastern Namibia. In contrast, the areas most devoid of carnivores are the Namib Sand Sea, where prey is scarce and water is lacking, and the area north of Etosha, where rural human population density is the highest in the country. Southeastern Namibia also has very low diversity of large carnivores, mainly because poisoning and persecution by farmers has driven out all large carnivores except for leopard. The distribution of large carnivores in Namibia is much more restricted than it was 100 years ago, but carnivores still persist over large parts of the country thanks both to the extensive farming practices which provide habitat for wildlife that carnivores prey on and, to a large extent, the tolerance of Namibian farmers who coexist with carnivores. While carnivores often conflict with livestock farmers, they do provide important services in the broader ecosystem such as regulating populations of species lower in the food chain.

State-protected areas, communal conservancies, community forests and concessions made up 40 per cent of Namibia's land surface in 2022. Such a large conservation network helps to keep natural ecological processes intact. The tourism value of these areas, supporting iconic cats such as leopard and cheetah, is also an important contribution to Namibia's economy.

The carnivore maps presented here show the areas where the species are likely to be resident. Individuals recorded outside of the main distribution range are usually dispersing immature animals looking for suitable places to establish themselves.

Photo: S Périquet

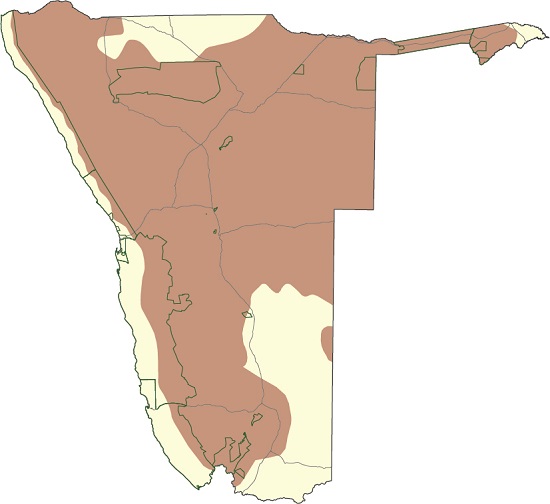

7.27 Distribution of cheetah43

The cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) was once widely distributed through Africa, India and the Middle East but now occurs in less than 10 per cent of its historical range. The largest remaining viable populations are found in southern Africa, and less than a quarter of these are in protected areas. Cheetahs are still found widely throughout the central and northwestern parts of Namibia, and even on the eastern edge of the Namib Desert.

Cheetahs have benefited from the large-scale removal of lions, leopards and spotted hyaenas from freehold farmlands, and from the recovery and reintroduction of wildlife onto livestock and game farms. They prey primarily on wildlife and even on livestock farms about 95 per cent of their prey is wildlife. Nevertheless, conflict with livestock and game farmers is the major threat to the cheetah population in Namibia, as it is elsewhere in southern Africa. There were an estimated 1,500 cheetahs in Namibia in 2022.

Photo: R Isaacman

7.28 Cheetah movements on central Namibian farmlands44

Cheetahs have an unusual pattern of social organisation. Some males establish territories, within which they frequently mark particular large trees and termite mounds with their urine and faeces which serve as 'communication hubs' to advertise their presence to other cheetahs. These territories overlap the larger territories of single females. Other males in the area roam around as 'floaters', either singly or in small groups of brothers or other related males.

The map shows the movements of a male that switched from being a floater (blue line), with a home range of 1,116 square kilometres, to being a territory-holder (green line) with a much smaller home range of 289 square kilometres. Territory-holders are usually more aggressive and heavier than floaters, perhaps as a consequence of having better access to food resources, but they eventually lose their territories when challenged successfully by coalitions of floaters.

Understanding the social organisation of cheetahs can help farmers to avoid conflict with them by adjusting their livestock management practices. For example, moving breeding herds away from communication hubs can minimise livestock losses.

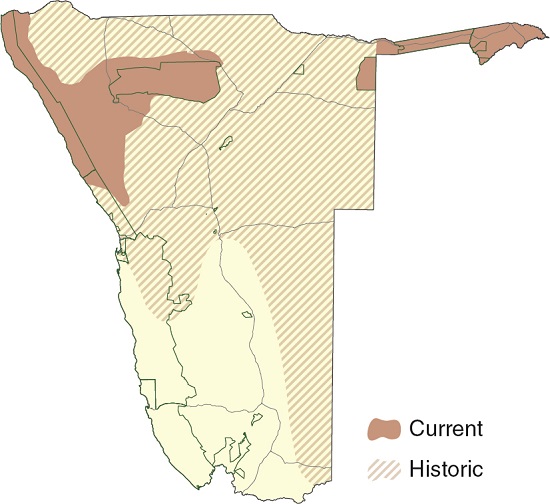

7.29 Distribution of lion45

Lions (Panthera leo) are now found in less than 8 per cent of their historical range in Africa and central Asia. This map also shows how severely their range has shrunk in Namibia since 1934, when it was noted that "very occasionally a wandering lion may be heard within a mile or two of Windhoek".46 Most lions now live in protected areas such as Etosha National Park, but lions also live in conservancies – communal farmlands – at low densities in the arid conditions of the northwest and savannas of the northeast.

Although lions are generally declining across Africa, four southern African countries – Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe – have not experienced the same declines because of the implementation of effective conservation practices, which make human–lion coexistence feasible. Most important is the maintenance of wildlife on which the lions can prey, and improved management practices that protect livestock, such as herding cattle during the day and confining livestock in lion-proof kraals (stockades) at night. Other measures include early warning systems that alert farmers to lions approaching their homesteads, and 'wildlife credit' schemes through which local residents receive payments for lion sightings by tourists or by camera traps.

Lions will, however, always be vulnerable to retaliatory killing by livestock owners. Other threats that Namibian lions may face are an increasing trade in body parts such as teeth, bones and claws, and an over-reliance on trophy hunting to address human–lion conflict or for pure profit. Internationally and in Namibia, lions are classified as 'vulnerable' according to the international IUCN Red list system of classifying organisms under threat. There were an estimated 800 lions in Namibia in 2022.

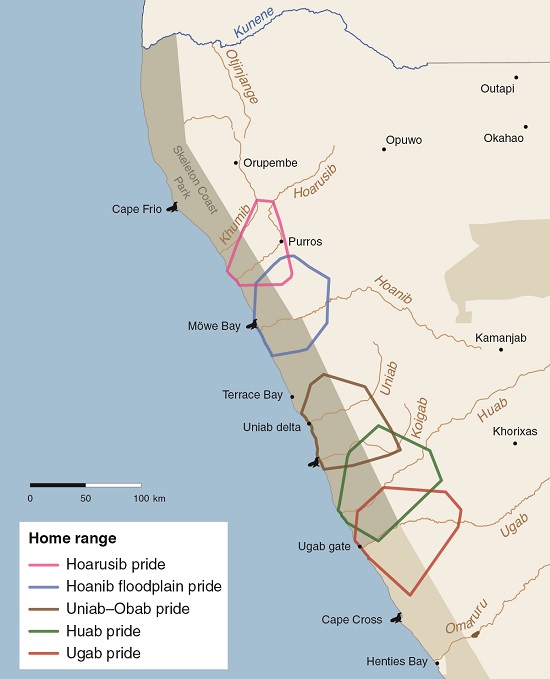

7.30 Lions along the Skeleton Coast47

The extremely arid Skeleton Coast Park is not an environment that one immediately associates with lions. Nevertheless, they do live in this area as shown in this map of home ranges of five prides that utilised the area between 2002 and 2017. The home ranges of the prides are centred around a number of ephemeral rivers, which provide conduits to the coast. Lions in these prides have learned to use marine and wetland resources; hunting and scavenging on cormorants and seals on beaches (as in the photo below), and flamingos and ducks at coastal springs. This complements their more usual prey of oryx and ostrich attracted to the green grass and freshwater springs along the rivers and further inland. The home ranges of these desert-adapted prides, at an average size of 4,726 square kilometres, are much larger than those of other prides elsewhere in Namibia and Africa. While these are the only lions known to feed on marine animals, it is not uncommon for lions to specialise on unusual prey, such as porcupine and elephant.

Photo: P Stander

7.31 Distribution of serval48

The serval (Leptailurus serval) is a slender, long-legged, medium-sized cat that is usually associated with wetlands and their fringing tall grasslands and reedbeds and the denser vegetation of floodplains and riverbanks. Servals are therefore naturally scarce in Namibia. However, records from central Namibia show that these cats are present at very low density in semi-arid savanna habitats too, possibly using riverbeds to move between patches of dense vegetation and water sources. Servals prey mainly on rodents, but also eat birds, reptiles, insects and sometimes other mammals such as small antelopes and hares.

Photo: L Hanssen

7.32 Distribution of leopard49

Of all the large cats in sub-Saharan Africa, the leopard (Panthera pardus) has the widest distribution with the least fragmentation and the most connectivity between populations. It is also the most adaptable of the cats, and leopards are found throughout Namibia except for the Cuvelai and the desert coast. The current distribution pattern is probably fairly similar to the historical distribution.

Leopards are opportunistic hunters that prefer medium-sized ungulates but hunt a wide range of species. Being secretive, they survive close to human habitation and most leopards in Namibia live outside national parks on freehold farmland. They are at times trapped or killed by farmers due to proven or perceived threats to livestock; leopards that kill livestock are often sub-adult males or old individuals, preying at times on calves, small stock and poultry. There were estimated to be 11,730 leopards in Namibia in 2022.

Photo: S Rankl

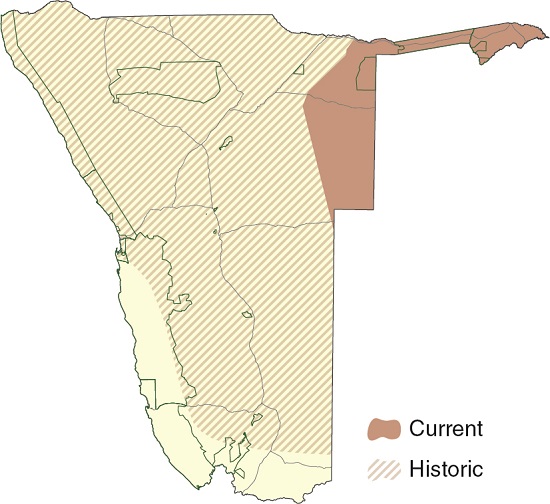

7.33 Distribution of brown hyaena50

The brown hyaena (Hyaena brunnea), a rather shy carnivore, is quite widespread across Namibia. Historic records show it as being absent or very rare in eastern Zambezi Region and rare in areas of southeastern ǁKharas Region. The current distribution is similar except for its absence in north-central Namibia, which is now densely populated with people. Small-stock farming may account for their absence in parts of southern Namibia, due to increased conflict and less tolerance of farmers towards carnivores. There were estimated to be 3,000 brown hyaenas in Namibia in 2022.

Brown hyaenas are solitary, opportunistic foragers that scavenge most of their food. On Namibian farmland they predominately scavenge from leopard and cheetah kills, while along the coast their diet mainly comprises seals and seabirds.

Photo: H Dillmann

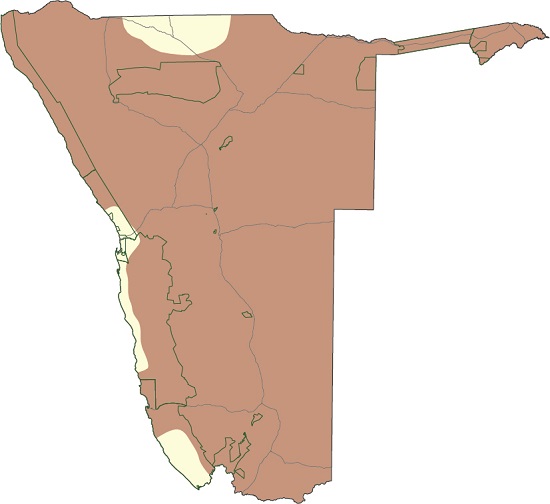

7.34 Distribution of spotted hyaena51

The spotted hyaena (Crocuta crocuta) has been almost completely eradicated outside of national parks and fenced-in private game reserves. Spotted hyaenas do occur outside protected areas in northwest and northeast Namibia, but mostly in areas with few people. They occur at low densities in parts of the Namib, where they have enormous home ranges of more than 4,000 square kilometres, over ten times bigger than those living in Etosha, which have ranges of less than 400 square kilometres.52

They live in social groups called clans in which the females are dominant and all breed, but the dominant female has priority over food that the clan obtains and consequently usually raises the most offspring. Spotted hyaenas are commonly thought to be scavengers but, in fact, they are competent predators in their own right. The population is decreasing across their range mainly because of habitat loss, shortages of prey and conflict with farmers over livestock predation. There were estimated to be fewer than 720 spotted hyaenas throughout Namibia in 2022.

Photo: T Figueira

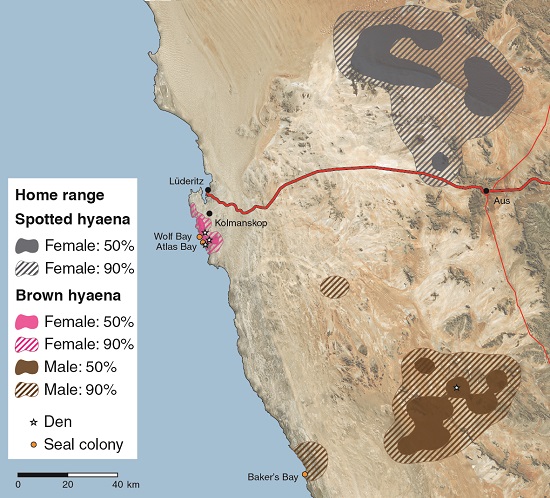

7.35 Hyaena home ranges in the southern Namib53

This map shows the areas covered by two brown hyaena individuals and a spotted hyaena. The inner, solid colours show the home ranges of these individuals where they spent 50 per cent of their time; the outer (striped) areas show the areas where the individuals were for much (90 per cent) of the time during the yearlong surveys.

The brown hyaena living at the coast (pink) fed largely on seals and seabirds and moved relatively little, averaging 18 kilometres a day. Most of the movements made by this female were between her various den sites and the seal colonies at Wolf and Atlas bays. Compare her home range to that of the male (brown shading) who resided further inland, making occasional foraging trips to the Baker's Bay seal colony and the Kaukausib spring, each more than 60 kilometres away from his den.

The spotted hyaena had an even larger range (grey) in the very marginal conditions of the southern Namib. This female's home range near Aus covered an area of just over 3,000 square kilometres. Spotted hyaenas can move tremendous distances; for example, a young male was photographed in the Khomas Hochland in 2018, 450 kilometres from where he lived near Aus in 2016.

Photo: P van Schalkwyk

7.36 Distribution of black-backed jackal54

The black-backed jackal (Canis mesomelas) ) is well known and widespread throughout Namibia. In some areas these jackals are considered to be pests for preying on small livestock. But they also serve farmers by controlling populations of rodent and insect pests, distributing seeds from fruits and berries and by scavenging on dead animals that could otherwise be a source of diseases to other animals.

While predator control measures undoubtedly kill many jackals, such measures may be ineffective in controlling the jackal population, and can result in higher levels of carnivore–livestock conflict. This is because non-selective trapping and poisoning depletes the availability of other small mammals, consequently raising the likelihood that jackals will kill livestock. Also, upsetting the social dynamics of the breeding pairs and other immature jackals in the area can result in more opportunistic breeding and a local increase in the jackal population. The map shows that, despite decades of effort trying to reduce jackal numbers, they have not been eradicated anywhere. Their population is regarded as stable.

Photo: P van Schalkwyk

7.37 Distribution of African wild dog55

The African wild dog (Lycaon pictus), with fewer than 550 individuals in 2022, is considered Namibia's rarest mammal and classified as 'critically endangered'. African wild dogs were originally widespread, extending far into southern Namibia, the pro-Namib and the northwest, but are now confined to the wetter northeastern parts of the country. This severe shrinkage of their range has occurred quickly, as wild dogs were still resident on the eastern edge of the Namib in the 1970s, and is probably because they are more visible than other carnivores, hunting in packs during daylight hours, and using communal dens which makes them vulnerable to farmer retaliation. Road kills are a significant cause of mortality. Their preferred prey is antelope up to the size of wildebeest, but they will attack livestock if their natural prey has diminished.

Photo: H & R Kennedy