Threats and challenges to Namibian wildlife

Namibia's wildlife does not exist in isolation from people and the impacts of human activities. There are many levels of interactions between people and wildlife; some of these are positive, while some are negative. As Namibia's human population increases, pressure on the land and its wildlife is also increasing. Land becomes transformed as wild areas are cleared for farming, industry or urban development, and natural habitat is lost or degraded through factors such as overgrazing, desertification, bush encroachment, erosion and pesticide use. Traditionally, wildlife was able to move freely to find water and grazing, but as the areas available to wildlife shrink, interactions between people living in rural areas such as conservancies and other communal areas and wild animals become more frequent and result in conflict. At the same time, human impacts cause major hindrances and threats to wildlife. These include impacts of habitat loss, persecution and poisoning, poaching and bush-meat harvesting, fences that impede movements, overharvesting of fish stocks, accidental catches of seabirds, power-line collisions, domestic cats and climate change. As human consumption and populations increase, these impacts will become more severe.

Finding a balance, between the health of wildlife populations and the land on which they depend and the livelihoods of rural people who live on this land, is a challenge.

Photo: J Mendelsohn

Photo: J Mendelsohn

Many of Namibia's animals utilise large areas of land and move long distances in response to rainfall, in search of grazing or prey. The restriction of free movement of wildlife by fences and roads causes direct mortalities and is also likely to reduce the genetic vitality of animal populations.

Photo: J Pallett

The kori bustard, the world's heaviest flying bird, is a frequent victim of collisions with power lines. It is estimated that over 50,000 bustards, cranes, flamingos and other large birds are killed in this way in Namibia and South Africa each year. Despite extensive research, there are still no fully effective solutions.

Photo: F Becker

Girdled lizards occur in mountains and rocky areas throughout much of Namibia, but are rarely encountered due to their shy nature. They are popular in the pet trade due to their impressive dragon-like appearance, and are often illegally collected and exported.

Species on the edge

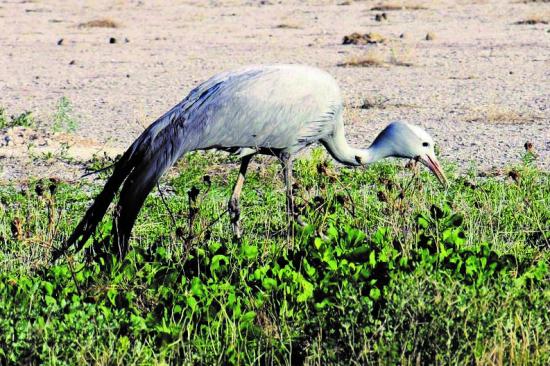

7.50 A species on the edge: Namibia's tiny, enigmatic blue crane population69

Photo: T Robertson

The small range of the blue crane in Namibia makes it particularly vulnerable to local pressures, whether they are natural or human-induced.

While many animals in arid areas have large ranges to meet their needs, others have surprisingly small ones. The blue crane (Grus paradisea) has the smallest range of the world's 15 crane species. The main population of around 25,000 birds is in South Africa, where it is classed as 'globally vulnerable'. An apparently highly isolated breeding population of blue cranes also occurs in Namibia, within the Etosha National Park and on the grasslands to the north of the park. Here, population numbers have declined from 300 birds in the 1970s, to 80 in 1992 and 60 in 1994. Since 2006, regular counts have not exceeded 35; the species is therefore regarded as 'critically endangered' in Namibia.

The map shows how cranes move seasonally within and around the park: they arrive in the park at the end of the dry season, and take up their nest sites on the seeps around Etosha Pan when the rains start. Once the chicks have fledged, the cranes move to grassland habitats in the northeast of the park and, from there, north to the Omadhiya lakes where they spend the dry months.

In these arid habitats blue cranes are dependent upon water for survival, roosting and rearing their chicks in safety from predators. They are therefore vulnerable to changes in the permanence and reliability of waterbodies. They are threatened by habitat loss and increased competition for space and resources, particularly when they leave the park for areas where numbers of both humans and stock have increased, and where illegal hunting has been reported.

Photo: A Jarvis

In the past Dead Vlei in the Namib received sufficient water to support the growth of large camelthorn trees. The trees died hundreds of years ago when the Tsauchab River was blocked by encroaching sand dunes.

Photo: F Jacobs

The cave-dwelling catfish, Clarias cavernicola, is known only from the Aigamas cave system in the Karstveld, and nowhere else on Earth. This small catfish is confined to a dark underground aquatic habitat in which the temperature and chemical characteristics of the water remain constant. Changes to the physical and chemical properties of the cave system and its water, such as those potentially caused by climate change, chance events and groundwater abstraction, may threaten the survival of this catfish. For this reason the population is considered critically endangered.70

Living with wildlife: human–wildlife conflict

Human–wildlife conflict occurs when people are directly affected by wildlife damaging or threatening their livelihoods or lives. Conflicts between people and animals in Namibia are most problematic on communal lands where large predators and herbivores are present and where farming families are often unable to bear the costs of damage caused by wildlife. The wildlife living in communal conservancies is, however, also a valuable natural resource, improving local livelihoods through tourism and hunting revenues. Balancing the costs against the benefits of wildlife to local economies is not easy.

7.51 Types of conflicts reported in communal conservancies, 201971

There are four main kinds of conflict: 1) attacks or predation on livestock by predators; 2) damage to crops, usually caused by feeding or trampling by elephant, hippo and antelope; 3) attacks on people, most frequently by crocodiles and elephants; and 4) other incidents, such as damage to water infrastructure by thirsty elephants. Livestock predation was most common in 2019, except in Kavango and Zambezi which were most affected by crop damage. These regions have extensive areas of smallholder crop farming and high densities of people, as well as diverse populations of mammals including a large number of elephants. By contrast in the arid northwest, the main impact of the small population of elephants was on infrastructure, especially of water pumps and pipes, but this impact was small in comparison to attacks on livestock by predators. Human attacks are usually infrequent, and in 2019 they amounted to 18 out of 9,502 reported incidents; nevertheless, these are the most distressing types of attacks for people living with wildlife.

7.52 Annual frequencies of human– wildlife conflicts, 2004–201972

The average number of incidents per conservancy across Namibia has been relatively stable, despite increases in the human and wildlife populations. Attacks on livestock dominate the conflict, followed by crop damage, other incidents, and attacks on humans. Predator populations have been stable or increasing in recent years and this is reflected in the slight rise in livestock attacks. In contrast, the number of incidents of crop damage has decreased since 2010, possibly as a result of mitigation measures adopted since this time. A range of measures are used to prevent or reduce conflict including chilli 'bombs' to deter elephants from damaging crops; predator-secure enclosures to protect livestock at night; and exclusion fences to allow people and livestock safe access to rivers away from crocodiles.

Photo: F Theart

Photo: F Theart

Namibia is home to several highly venomous snake species. Snakes are often the cause of human–wildlife conflict and consequently many snakes are killed on sight, whether they are venomous or not. The zebra snake (Naja nigricincta) and black mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis) both occur in densely populated areas, and the zebra snake is the species most commonly involved in snakebite incidents. By contrast, the black mamba, the subject of many legends and stories, rarely bites humans.

7.53 Species-specific conflict incidents in communal conservancies, 201973

Sixty-three of 86 registered conservancies reported conflict incidents in 2019. The regional groupings used in the charts reflect the broadly different habitats they encompass. The Okavango, Kwando, Zambezi and Chobe river systems in the northeast are important for both people and wildlife, and the most important conflict species here are elephant, crocodile and hippo. Elsewhere, hyaena or jackal top the list, with cheetah also causing conflict in the northwestern conservancies. Interestingly, although lions are often perceived to be a significant threat, they are actually responsible for fewer incidents than many of the other carnivores.

Photo: J Mendelsohn

Crimes against wildlife

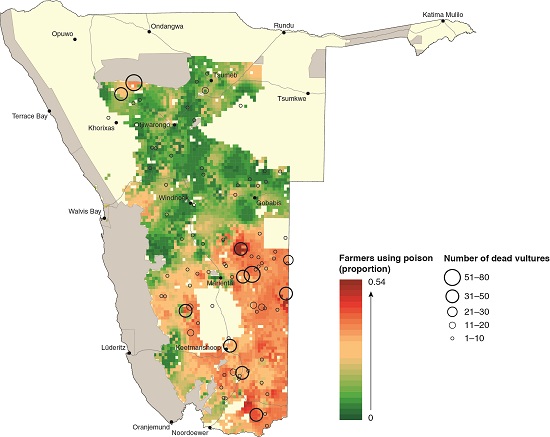

7.54 Poison use and vulture deaths on freehold farms, 2000–201574

Poison is used by livestock farmers to control predators, but often has a significant impact on non-target scavenger species such as vultures. Although the use of poison to control predators has been illegal in Namibia since 2001 this practice is still prevalent, as shown on the map. On average, 20 per cent of Namibia's freehold farmers use poison to control predators with the most frequent use being in the south of the country where about half the farmers use it. The symbols show data on a total of 804 dead vultures reported on freehold farmlands between 2000 and 2015, of which around three-quarters (590 birds) died from ingesting poison. Almost all of the others drowned (199 birds), while just a few (7 birds) died from other causes, such as electrocution or being shot. Research indicates that the levels of poison use on communal farmlands are significantly lower than on freehold lands.

Photo: A Botha

In addition to accidental poisoning as shown above, a further serious threat to vultures has arisen in recent decades. As the poaching of high-value wildlife in north-eastern Namibia and northern Botswana has increased, vultures are being deliberately poisoned by poachers. Vultures soar over vast distances to forage, circling and coming down to land when they find a carcass. Thus, their presence can alert wildlife authorities to fresh carcasses. Poachers lace carcasses with poison in order to reduce vulture numbers and avoid detection. Hundreds, probably thousands, of vultures, and other scavenging species, have been killed as a result of these poisonings. Vultures are also deliberately poisoned for the harvesting of body parts for use in the traditional medicine trade. Of Namibia's six species of vultures, one is classified as Extinct as a breeding species, one is Critically Endangered, two are Endangered and two are Vulnerable.75

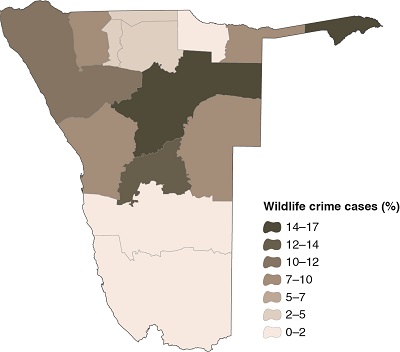

7.55 Wildlife crime, 201976

Wildlife crime is driven by complex factors. Poachers are mostly rural people with limited economic opportunities, who seek a way out of poverty or simply food to eat. Yet high-value wildlife products such as pangolin scales, elephant ivory and rhino horn are the lucrative commodities of organised crime syndicates supplying illicit international markets. Most dealers and kingpins are ruthless criminals involved in a wide range of illegal activities. They recruit rural residents to become poachers, while involving a variety of aiders and abettors with the lure of quick cash.

The effects of wildlife crime on Namibia's economy, biodiversity and local livelihoods are severe and diverse. Highvalue species such as rhinos face the threat of local and even global extinction. Vast resources, which could be used for national development or conservation priorities, are now spent to combat wildlife crime. Such factors have made wildlife crime one of the central conservation challenges facing Namibia.

Strong collaboration between government, NGOs, local communities, the private sector and international funding agencies has enabled Namibia to strengthen its efforts to combat wildlife crime. Law-enforcement results in recent years have been impressive. The map shows the distribution of wildlife crime cases in 2019. In 2019 there were 174 cases and 363 arrests related to the most-targeted high-value species: pangolin, elephant (Loxodonta africana), and black rhino (Diceros bicornis) and white rhino (Ceratotherium simum) combined (see graph). Over half of the rhino-related arrests were pre-emptive, occurring before a rhino was poached, thus saving the targeted animals while still resulting in the conviction of the perpetrators planning the crime.

In the long term, alleviating rural poverty and reducing international demand for illegal wildlife products will be key aspects to minimising wildlife crime.

Photo: J & S Hurd

Pangolins have become the most trafficked wild animals on Earth, yet very little is known about them or the health of their populations. The ground pangolin (Smutsia temminckii), which occurs in Namibia, plays an important ecological role: a single pangolin can eat over 70 million ants and termites per year providing natural control of potential pest species which can negatively impact grasslands and crops and destroy fence posts and other infrastructure.77