Education

Schooling in Namibia is a significant activity. In 2011, 41.3 per cent of the population was at early childhood development, primary or secondary school. Furthermore, spending by the government of public money on education has been high, close to 30 per cent of the annual revenue budget in recent years. Education has always been important to Namibians, with enrolment rates among the highest in Africa, even before independence. Reflecting this demand for schooling, most schools in Namibia were started by parents as private initiatives, often as rudimentary structures under village trees.53 Despite high enrolment rates, the quality of educational achievement is a major concern.54

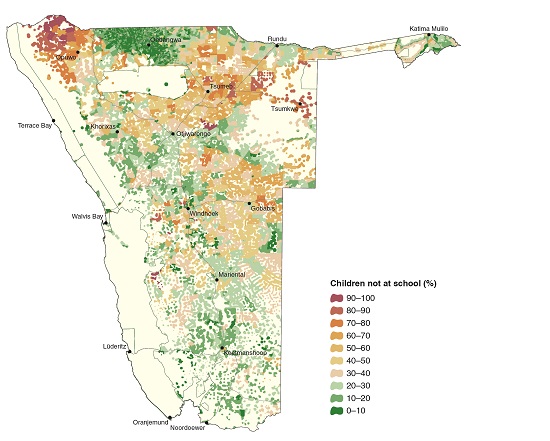

9.35 Proportion of children aged 6–18 not attending school, 201155

Although demands for schooling are generally high, school attendance in some areas is lower than expected. This is especially true in northern Kunene and more remote areas of Oshikoto, Otjozondjupa, Kavango West and Kavango East. Many of the children thus affected come from marginalised Ovahimba and San communities. Factors that keep children out of school include a lack of access to schools, demands on children to work at home or earn money elsewhere, and teenage pregnancies.

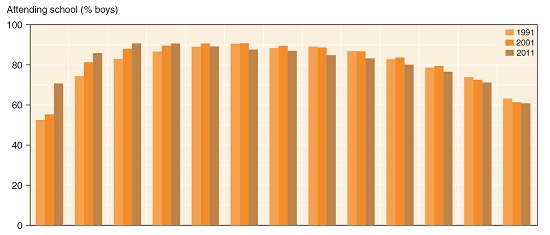

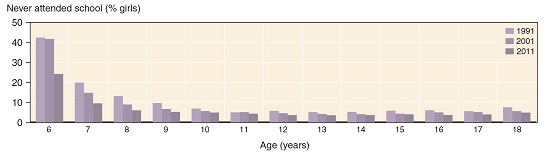

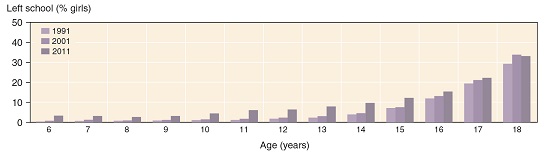

9.36 School attendance and drop-out rates in 1991, 2001 and 201156

The six graphs alongside show the proportions of girls and boys, aged 6–18 years, who attended school, who never attended and who left school prematurely. In most developing countries more boys than girls go to school. The reverse is true in Namibia where enrolment rates of girls were 2–4 per cent higher than those of boys in 1991, 2001 and 2011. This was true for girls of all ages. It is then not surprising that higher proportions of boys had never been to school, and more boys of 16 years or younger had left school prematurely. Enrolments of boys were highest between the ages of 8 and 11 years, while those for girls were highest between 8 and 14 years. The two lowest graphs show how proportion of boys and girls who left school prematurely increased over the years.

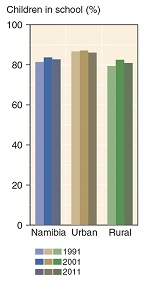

9.37 Proportion of children aged 6–18 years at school in 1991, 2001 and 201157

Enrolment rates rose nationally from 81.4 per cent in 1991 to 83.7 per cent in 2001 before slipping to 82.7 per cent in 2011. Similar changes occurred in urban and rural areas, and in most regions. Exceptions were in Kavango West and Kunene where enrolment rates decreased between 1991 and 2011. By contrast, enrolment rates increased over the same period in ǁKharas, Kavango East and Ohangwena. In the absence of urban schools in Kavango West, migration to schools in Rundu in Kavango East might explain why enrolment rates increased in the eastern region and declined in the western one.

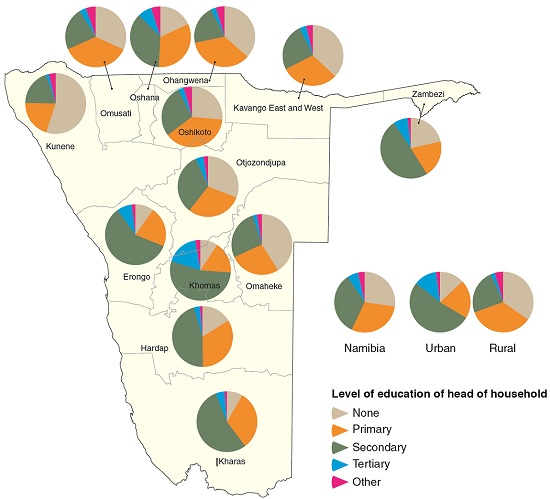

9.38 Levels of formal education of household heads, 201158

Older Namibians generally have lower levels of education than younger people, simply because many older people did not go to school or left school at an earlier age. One consequence of these lower levels of schooling is the high number of households who are headed by people who have relatively little formal education. Children in these homes may be disadvantaged in multiple ways, for example, in lacking guidance, encouragement, role models and resources to do well at school.