Urban land

Land uses in urban areas are extremely concentrated. This is exemplified when considering where people in Namibia have settled: in 2020, about 1.35 million people lived in 13,600 square kilometres of urban land in comparison with about 1.25 million people spread across 810,000 square kilometres of rural Namibia, at respective densities of 99.3 and 1.5 people per square kilometre.

Urban land is used for three major purposes: to facilitate commerce (including the production and supply of goods); to provide homes for residents; and to supply services to residents and the nation. The latter includes public services that may be managed from the capital city or a regional centre but delivered elsewhere, for example facilities for health and well-being.

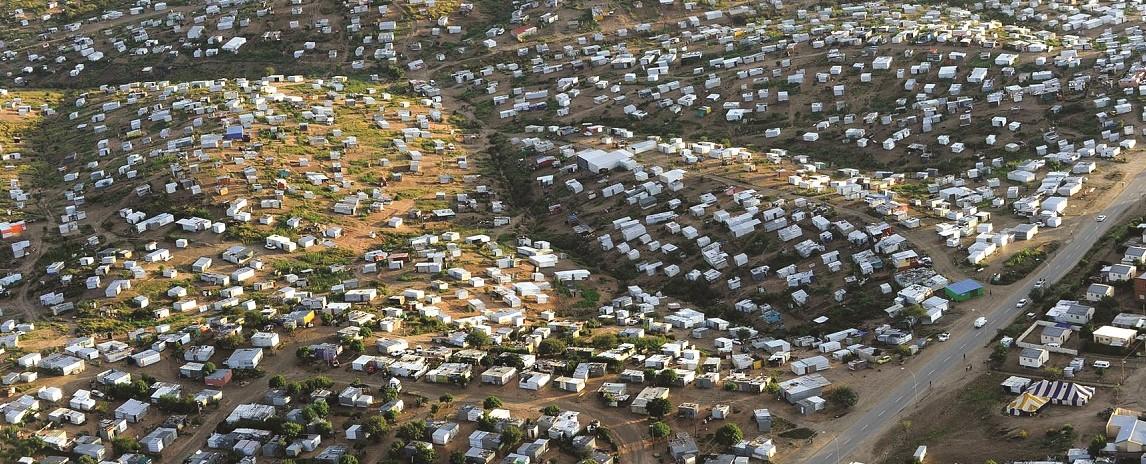

Photo: H Denker

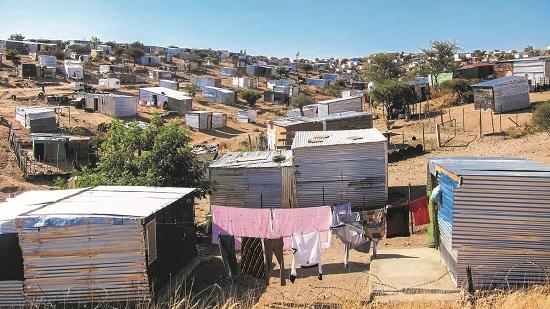

From above, the twinkling roofs of corrugated-iron shacks of Windhoek stretch as far as the eye can see, attesting to the rapid rate of urbanisation in Namibia. The growth of urban shacks far exceeds the growth of formal housing. At present rates of growth, urban shacks will be the predominant type of Namibian dwelling in 2025, surpassing the number of rural homes by 2023 and the number of formal urban homes by 2025 (figure 9.28).

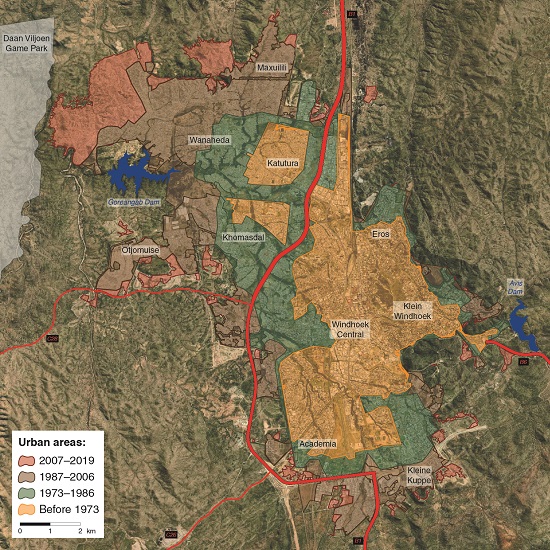

An interesting distinction between urban and rural land is that urban zones can expand, rural areas cannot. Namibia's urban land has expanded in two ways: through villages or settlements being classified and upgraded into urban areas; and by the extension of boundaries of declared urban areas (figure 8.17). However, it is the growth of urban populations that is most conspicuous. Migration to urban areas has accelerated as more and more rural people move to towns to secure incomes, services and goods – in essence, seeking to make a better life for themselves and their children.

Urban areas face a multitude of challenges. Current management, and regulatory and service systems are unable to adapt to the fast pace of urban migration. Urban development has become more informal, less ordered. A lack of capacity to provide land, housing, jobs and services leaves many thousands without access to reasonable living conditions. The major challenges seem insurmountable if solutions focus on provision – the provision of services, jobs and housing. Yet, migrants provide an important opportunity: to boost the economy. Economic growth allows for the creation of enterprises and for savings as capital assets; it facilitates the growth of national and intergenerational wealth; and improves access to basic human needs. Much of this will happen when newcomers to towns have land with secure tenure on which they can build and expand their own capital assets and develop and grow their own informal and formal enterprises. In this way, residents can expand the value of informal settlements and the informal economy.

8.16 Urban areas, 2002–202021

Urban areas are rapidly changing landscapes, consisting of both formally declared villages,22 settlements, towns and cities shown on this map, and of undeclared, embryonic urban areas where goods and services are concentrated. This map shows the declared boundaries of urban areas in 2002 and in 2020; those without a borderline were not yet formally declared urban areas in 2002.

Many urban areas are faced with the challenge of ‘leapfrog developments’. These are housing and commercial developments that occur just outside of the jurisdiction of an urban area, leapfrogging the urban edge. The developments benefit from services provided by the nearby town, but they make little contribution to the town’s tax income, upkeep and improvement. Leapfrog developments are found on communal and private lands surrounding urban areas. Some urban areas, such as Windhoek, have massively increased their boundaries to prevent leapfrogging.

August 2004

Photo: Google Earth

July 2019

Photo: Google Earth

Aerial photos of the newly established formal urban settlement of Ongha between Ondangwa and Oshikango show its growth between 2004 and 2019. Informal urban areas typically develop where there is ready access to goods, services and opportunities. Often these are along national roads, at crossroads, or where there may be a school and some small shops. For years Ongha was one such prime area for settlement; access to services and informal land sales and property speculation have driven its growth. Over a period of 10 years the number of new structures grew tenfold.

8.17 Growth in urban areas23

Here, the largest towns and cities in Namibia and their growth footprints are shown for recent decades.Windhoek

Windhoek's expansion to the south, west and east has been constrained by the steep margins of the rift valley in which the city lies. Much of the open space within the city has been retained for future expansion of infrastructure or low-density housing. With no legally available open land, urban migrants have been forced to settle on Windhoek's northwestern outskirts where they are far from services and commercial activities.

Rundu

Following Windhoek, Rundu now has the second largest population of any single urban area in Namibia. Its growth has largely been driven by its strategic location as the only significant town within a radius of about 270 kilometres, as well as being on the road along which all traffic to and from northeastern Namibia passes. Rundu was established on the banks of the Okavango River, and has therefore grown to the south, east and west.

Oshakati–Ongwediva

The conjoined towns of Oshakati and Ongwediva were founded in the 1960s. Oshakati was established as the regional capital. It grew rapidly and was an important military base. Ongwediva was a Finnish mission that was later converted to a dormitory town for local government workers. Both towns grew rapidly on higher land lying between iishana drainage lines and along the main road connecting the two. Today, the Oshakati–Ongwediva stretch is the only place in Namibia where one can drive between two towns without passing through rural land.

Ondangwa

Ondangwa, lying south-east of Oshakati–Ongwediva, stretched linearly as businesses were established haphazardly next to the main road and then formalised incrementally over time. Such linear structures function less efficiently than radial urban layouts.

Walvis Bay

Walvis Bay has been confined to the west by the Atlantic, and the development of its core has thus expanded concentrically around the port and main commercial hub. The residential area of Langstrand, lying 15-20 kilometres north, was added to Walvis Bay as a separate development.

Rehoboth

Being bounded to some extent by the Oanab River to the south and hills to the west, Rehoboth has expanded over the years to the east and north where the terrain is flat.

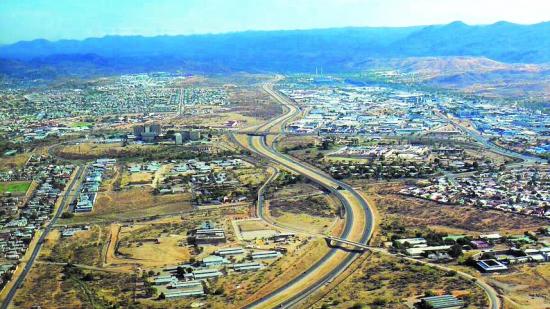

Photo: J Mendelsohn

The B1, Namibia's main national road, passes through Windhoek from the south, and continues northwards through farmland. These roads provide many rural Namibians with their only access to services and the modern economy. Road reserves on either side of the roads are kept open in case roads need to be widened; they make up about 3,000 square kilometres. Buildings are not permitted within the reserves, but the land may be used for grazing by adjacent farmers. However, in some places, settlements have developed along roads, which impede the flow of traffic.

8.18 Areas of urban land, 2002 and 202024

The proportion of urban Namibia grows as people move to existing towns, but also as new settlements are proclaimed in places where natural growth has taken place. Windhoek is exceptional in having declared rights over more land than all the other towns and villages in Namibia combined. Much of this space is empty land and privately owned, but under the control of the municipality.

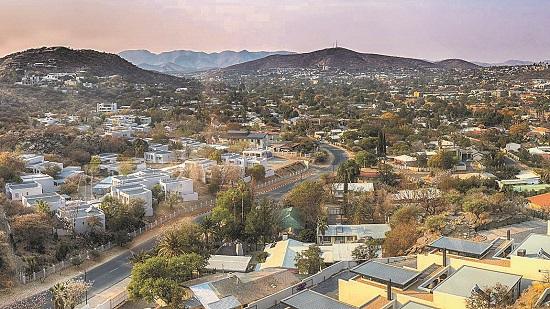

Photo: R Isaacman

Photo: JB Dodane

Formal housing meets informal housing in Windhoek. For most long-established residents in towns and cities there is a clear distinction between urban and rural areas. Most of these residents live in formal, middle- and upper-income homes (left). Recent migrants who live in informal settlements (right) are now also separated from their rural origins, but many of these shack dwellers retain strong social and economic connections to their rural villages. The connections are retained through family relationships and inherited rights to land and livestock held by their families. Rural family members have at the same time gained access to new benefits from their urban relatives, notably from remittances. Whereas many families were once associated with defined villages, now they are distributed across different properties and economic circumstances.

Source: https://www.afriterra.org/

For hundreds, if not thousands, of years artesian springs attracted people to the area that became Windhoek. Hereros called the place Otjomuise, 'Place of Steam', while Namas used the name |Ai-||Gams, 'Firewater', in reference to hot water in the springs. This is a map of Windhoek in 1892. The first permanent buildings were erected in the 1840s, and the settlement then grew slowly until it was formally established in 1890 with the laying of the foundation stone of the fort, now known as the Alte Feste. Plots were established to produce food in Klein Windhoek, while the main town grew in the area of presentday central Windhoek. The map is reproduced courtesy of Afriterra's free cartographic library, <https://www.afriterra.org/>.