Farming

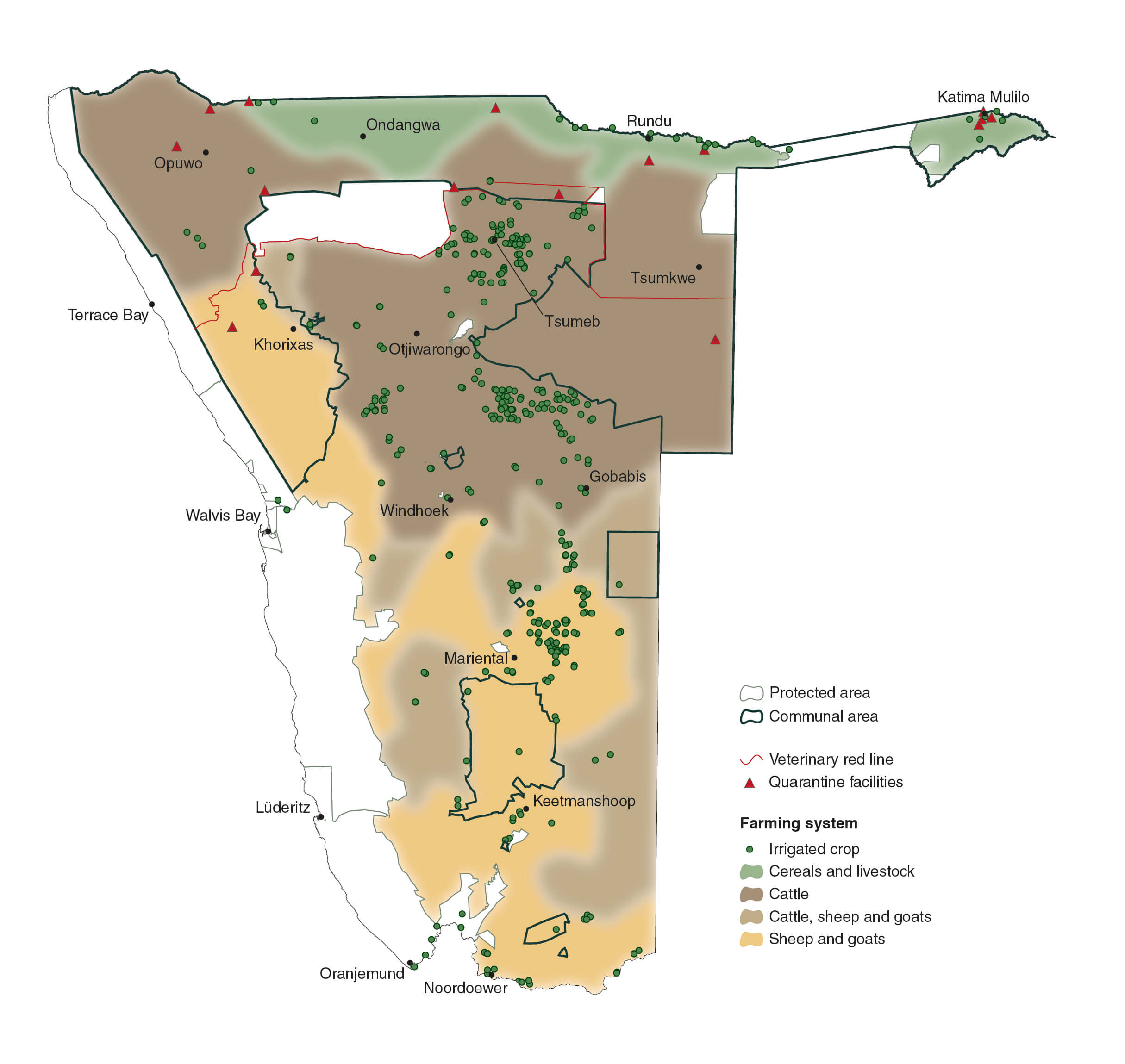

8.02 Major farm products and land uses4

Much of Namibia's land is best suited to small and large livestock farming at low stocking rates. In the central areas of the country farmers focus mostly on producing meat from cattle, while in the south farmers mainly produce meat and wool from sheep and goats. Irrigation schemes scattered throughout the country are used to produce a variety of crops, including maize, wheat, sunflowers and high-value fruits and vegetables. Maize and sunflowers are also grown on rain-fed and irrigated fields in the Otavi–Grootfontein–Tsumeb area. Other dryland crops are grown on the northern communal lands where most rural homesteads grow pearl millet (locally known as mahangu) and/ or maize and sorghum for domestic consumption. Less than half of these households keep small numbers of goats and cattle. Most livestock in the northern communal areas are kept as an asset for security or savings, and not for commercial production.

The veterinary cordon fence, or 'red line', across northern Namibia protects livestock to its south from infectious diseases such as foot-and-mouth and lung sickness. Meat products from this disease-free southern zone can then be exported. Quarantine facilities in northern Namibia are used to keep cattle in isolation before their meat can be processed and sold elsewhere.

8.03 Cattle numbers in Namibia's veterinary districts, 1971–20185

The graphs depict the total number of cattle in each of Namibia's ten veterinary districts (shown on the map). Note that the graphs have different vertical scales, and that gaps reflect missing data rather than zero values. Cattle numbers in the four northern communal districts increased substantially over these 50 years. The total number of cattle in those northern areas amounted to about 1.6 million by 2018, about three times higher than in the 1980s and early 1990s. Much of this increase can be attributed to wealthy urban residents stocking cattle posts and recently acquired farms in communal areas with cattle, which they keep as savings.

Most of the central and southern areas show a reverse, decreasing trend, with the total number of cattle dropping from about 1.5 million in the 1970s and 1980s to 1.0 million by 2018. The greatest declines in numbers were in the veterinary districts of Kunene South and East, Otjiwarongo and Otavi, Grootfontein and Omaheke, and Windhoek and Okahandja. Much of the decline is probably due to the conversion of commercial beef farms into game, tourism or resettlement farms, and reduced investment in commercial beef production.

Photo: J Mendelsohn

The saline Andoni and Ombuga grasslands north of Etosha National Park provide grazing for thousands of cattle. Many of the animals are moved to these grasslands when grazing in the more densely populated areas of the Cuvelai has been depleted. This shift of cattle between their homes and distant cattle posts is known as 'ohambo', a practice that has been used for centuries, especially during droughts. Nowadays, cattle are often kept permanently at cattle posts manned by herders. Tens of thousands of Namibian cattle are also grazed at ohambo areas far into southern Angola.

8.04 Sheep numbers in Namibia's veterinary districts, 1971–20186

These are the total numbers of sheep in each of Namibia's ten veterinary districts (shown on the map). Note that the graphs have different vertical scales. Namibia had between 3 million and 4 million sheep in the 1970s, almost double the numbers of the last decade. Much of this reduction was due to the collapse of the karakul industry.

Between 60 and 80 per cent of all sheep in Namibia have been farmed in the southern regions of Hardap and ||Kharas where their numbers have also decreased. Only in the Central North have sheep numbers increased significantly in recent decades. There are few sheep in Kavango and virtually none in Zambezi where they are limited by disease, such as food-and-mouth, and by poisoning from eating toxic plants.

Photo: J Mendelsohn

Sheep in Namibia are nowadays dominated by breeds suited to the production of mutton, most of which is exported to South Africa. However, for many years karakul sheep bred for their lamb pelts were in the majority. For example, there were about 3.8 million karakul in the mid-1970s. Their numbers plummeted in the 1980s when demand for pelts by the fashion industry dropped.

8.05 Goat numbers in Namibia's veterinary districts, 1971–20187

These graphs depict the total numbers of goats in each of Namibia's ten veterinary districts (shown on the map). Note that the graphs have various vertical scales. In recent years, most of Namibia's goats have been kept or farmed in the Central North, Kunene North, and Hardap and ||Kharas veterinary districts. Similar to the trends seen for cattle and sheep numbers, goat numbers have also declined in most central regions of the country. The opposite occurred in Central North, Kavango, and Hardap and ||Kharas districts where numbers have increased.

Photo: J Mendelsohn

Most goats and sheep are in the southern and western regions of Namibia. Small-stock herds are often paired with puppies or young donkeys that grow up as adopted members of the flock; the adopted member provides a measure of protection to the herd against predation.

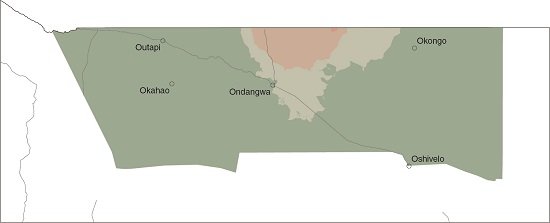

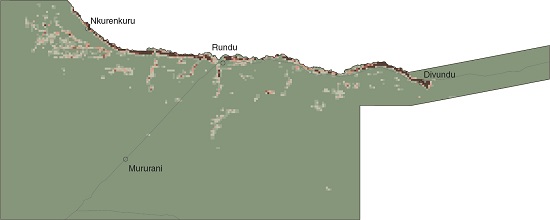

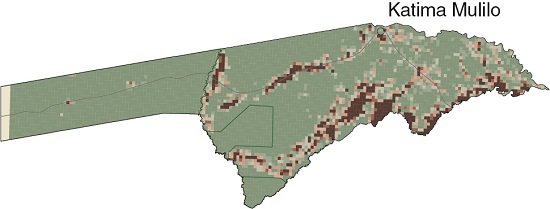

8.06 Proportions of land cleared for crop farming in areas of northern Namibia8

Central North 1973

Central North 1987

Central North 1997

Central North legend

Kavango 1943

Kavango 1972

Kavango 1996

Kavango and Zambezi legend

Zambezi 1996

Zambezi 2018

Four main changes have affected natural vegetation cover over large areas of Namibia. First, and affecting the smallest areas, has been the increasing presence of invasive alien plants. Second, has been the conversion of savanna woodlands into shrublands by repeated, intense fires. Third, has been the major increase in bush density due to bush encroachment, largely because of limited fires. Finally, the greatest loss of natural bush and tree cover has been from the clearing of woodland and forest for crop fields.

The largest area cleared for crops is in central northern Namibia (former Owamboland). It is this clearing of natural vegetation that gives the Namibian part of the Cuvelai a paler colour in satellite images than the Angolan Cuvelai immediately north of the border, where fewer people live, and more trees remain. Large areas of woodland have also been cleared for crops in Kavango West and Kavango East. In 1943 all crop growers lived along the Okavango River, but more and more people moved southwards to establish homes and new fields along roads, drainage lines and interdune valleys. The total area cleared in Kavango West and Kavango East increased at an average rate of about 4 per cent per year between 1943 and 1996. East of the Kwando River in Zambezi Region, 121,568 hectares had been cleared by 1996; another 75,600 hectares were cleared by 2018 at an average rate of about 2.2 per cent per year. In former Owamboland, the rate at which new land was cleared after 1996 was about 2 per cent per year in the most densely populated areas and 9 per cent per year in sparsely populated outlying areas.

Smallholders in these areas seldom apply fertilisers or manure, with the result that soil nutrients are generally depleted over several crop seasons. New fields are then cleared. As a consequence, most areas cleared of their indigenous vegetation now lie abandoned and much more land has been cleared (about 20,000 square kilometres) than is used for crops in any one year (3,000 square kilometres). Additional fields were also cleared following cycles of unusually high rainfall, which were then abandoned when conditions reverted to the usual mix of good and bad years of rain.

» View/download map - locations (jpg)

» View/download map - Central North 1973 (jpg)

» View/download map - Central North 1987 (jpg)

» View/download map - Central North 1997 (jpg)

» View/download legend - Central North (jpg)

» View/download map - Kavango 1943 (jpg)

» View/download map - Kavango 1972 (jpg)

» View/download map - Kavango 1996 (jpg)

» View/download map - Zambezi 1996 (jpg)

» View/download map - Zambezi 2018 (jpg)

Photo: Google Earth

Areas cleared for crops have increased rapidly for two reasons. First, populations have grown rapidly over the past hundred years. Second, is the need to clear new fields frequently, especially in areas where the soils hold few nutrients and often become depleted after 3–4 years of cropping; farmers must then clear virgin woodland and forest for new fields. The fertility of the soils becomes even more depleted through cultivation, tilling and exposure to wind. Without concerted efforts, it is near impossible for the slow-growing indigenous plants to re-establish on cleared land.

By the start of the twenty-first century, just over two million hectares had been cleared in Namibia. Assuming a conservative figure of 50 trees per hectare,9 this equates to the clearing of approximately 100 million trees from those fields by 2000. If the area cleared increases by three per cent each year (see below), another three million trees are lost each year in northern Namibia. [Image centre 17.96° S, 15.05° E]

Photo: J Mendelsohn

Smallholders in northern Namibia grow crops using a low-input, low-output production system. This reduces the chances of losing or wasting costly inputs in an unpredictable environment where the risk of failure due to drought and pests is high. Much care is also taken to store produce for as long as possible, as another measure to guard against the consequences of crop failure in a following year. Families often have several granary baskets, locally known as omashisha, outside their houses.

Photo: J Mendelsohn

This photo illustrates a typical smallholder farmstead in northern Namibia where each family normally cultivates 1–5 hectares of land. About 70 per cent of all areas cultivated for cereals are under pearl millet (locally known as mahangu) and sorghum, while maize and wheat make up 25 per cent and 5 per cent of production, respectively. Melons, beans and nuts are often intercropped with mahango and maize. All of these crops can be stored for long periods for later use. Approximately 90 per cent of cleared lands 'belong' to smallholders who consume their harvests, and thus very seldom have any excess to sell.

Photo: J Mendelsohn

The vast majority of crops are rain fed and grown on dryland fields. These are concentrated in northern Namibia where soils and rainfall are better suited to crops than the more arid central and southern areas of the country.

Photo: J Mendelsohn

Increasing domestic needs for cash and rising demand for food products in the rapidly expanding northern towns have encouraged rural smallholders to produce more vegetables. Most of these producers are located near busy roads along which their produce can be efficiently transported to urban markets.

Photo: J Pallett

Photo: J Pallett

The most effective use of irrigation is for high-value produce, such as vegetables and the grapes and dates grown at Naute Dam (first photo above) and along the Orange River (second photo above). Other substantial sources of water from the Stampriet aquifer, karst aquifers in the Otavi–Grootfontein–Tsumeb triangle, Hardap Dam and the Kunene and Okavango rivers are used to irrigate various fruits, vegetables, cereals and fodder plants. An irrigation scheme is also planned for Neckartal Dam. Other than ample supplies of water, these irrigation schemes usually require their soils to be fertilised and carefully managed.

8.07 Game farming, 202010

Some farms and communal conservancies utilise game for trophy hunting, as breeding stock or for game meat and hide production. The value of animals sold for trophy hunting far exceeds the value of animals utilised for local game meat consumption and the sale of hides. Some game farms breed high-value animals to sell to other breeders, game farmers and trophy-hunting operators. Game farms also attract relatively high-paying tourists, most of them from foreign countries.

Shoot-and-sell operations for commercial game meat and meat products, and trophy hunting, can take place on any registered hunting farm with a permit issued by government. Under Namibian law, listed 'huntable game', 'huntable game birds' and 'exotic game' species, in areas that are enclosed by a game-proof fence and at the discretion of the landowner, can be hunted by permit-holding hunters under specified conditions. Almost 700 farms covering more than 3.5 million hectares are registered as trophy-hunting farms.11 In addition, conservancies managing over 10 million hectares of communal land earn income from game hunting in partnership with hunting operators.

Most trophy hunting is of medium-sized game such as oryx, warthog, springbok, kudu, red hartebeest, zebra and eland. Hunting of specially protected large game species such as elephant, hippopotamus and buffalo occurs mainly on communal conservancies with hunting concessions, as these animals are rarely found or kept on freehold land. Trophy hunting is estimated to remove less than one per cent of the national wildlife stock each year which is less than the normal rate of population growth.